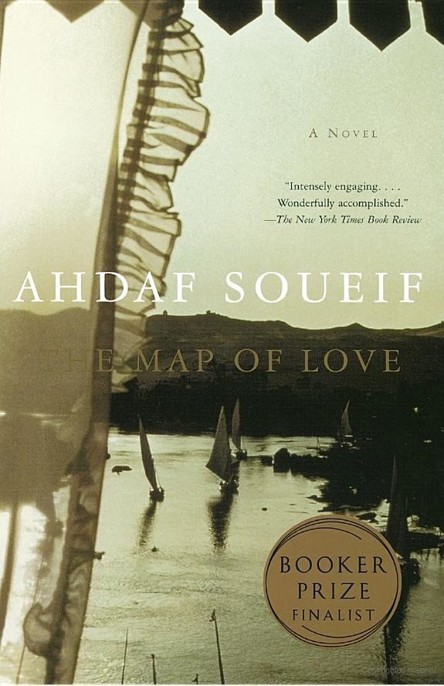

The Map of Love

Authors: Ahdaf Soueif

THE MAP OF LOVE

Ahdaf Soueif was born in Cairo and educated in Egypt and England. She is the author of

Aisha, Sandpiper

, and

In the Eye of the Sun.

AHDAF SOUEIF

Aisha

Sandpiper

In the Eye of the Sun

The Map of Love

FIRST ANCHOR BOOKS EDITION, SEPTEMBER 2000

Copyright © 1999 by Ahdaf Soueif

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Anchor Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in hardcover in the United Kingdom by Bloomsbury Publishing, Pic., London, in 1999.

Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Soueif, Ahdaf.

The map of love / Ahdaf Soueif.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-78355-4

New York: Anchor Books, 2000.

PR6069.O78 M37

00-35531

v3.1

For Ian

It is strange that this period [1900–1914] when the Colonialists and their collaborators thought everything was quiet — was one of the most fertile in Egypt’s history. A great examination of the self took place, and a great recharging of energy in preparation for a new Renaissance.

Gamal Abd el-Nasser,

Abd el-Nasser,

The Covenant

1962

Even God cannot change the past.

Agathon (447–401

BC

)

— and there, on the table under her bedroom window, lies the voice that has set her dreaming again. Fragments of a life lived a long, long time ago. Across a hundred years the woman’s voice speaks to her — so clearly that she cannot believe it is not possible to pick up her pen and answer.

The child sleeps. Nur al-Hayah: light of my life.

Anna must have put aside her pen, Amal thinks, and looked down at the child pressed into her side: the face flushed with sleep, the mouth slightly open, a damp tendril of black hair clinging to the brow.

I have tried, as well as I could, to tell her. But she cannot — or will not — understand, and give up hope. She waits for him constantly.

Amal reads and reads deep into the night. She reads and lets Anna’s words flow into her, probing gently at dreams and hopes and sorrows she had sorted out, labelled and put away.

Papers, polished and frail with age, sheets and sheets of them. Mostly they are covered in English in a small, firm, sloping hand. Amal has sorted them out by type and size of paper, by colour of ink. Other papers are in French. Some are in envelopes, some loosely bundled together in buff folders. There is a large green journal, and another bound in plain

brown leather, a tiny brass keyhole embedded in its chased clasp. The key Amal found later in the corner of a purse made of green felt — a purse with an unwilling feel to it, as though it had been made in a schoolroom project — and with it were two wedding rings, one smaller than the other. She looked carefully at the etchings inside them, and at first the only part of the inscription she could make out on either ring was the date: 1896. A large brown envelope held one writing book: sixty-four pages of neat Arabic ruq a script. Amal recognised the hand immediately: the upright letters short but straight, the sharp angles, the tail of the ‘ya’ tucked under its body. The definite, controlled hand of her grandmother. The paper is white and narrow-lined, bound between marbled grey boards. The stiff pages crackle and resist. When she smooths them open they lie awkwardly, holding a rigid posture till she closes the book again. Some newspaper cuttings:

a script. Amal recognised the hand immediately: the upright letters short but straight, the sharp angles, the tail of the ‘ya’ tucked under its body. The definite, controlled hand of her grandmother. The paper is white and narrow-lined, bound between marbled grey boards. The stiff pages crackle and resist. When she smooths them open they lie awkwardly, holding a rigid posture till she closes the book again. Some newspaper cuttings:

al-Ahram, al-Liwa, The Times

, the

Daily News

and others. A programme from an Italian theatre. Another purse, this time of dark blue velvet. She had upended it over her palm and poured out a string of thirty-three prayer beads of polished wood with a short tassel of black silk. For the rest of the day her hand smelled faintly of aged sandalwood. Some sketchbooks with various drawings. Several books of Arabic calligraphy practice. She flicked through them, noting the difference in flow and confidence. Several books of Arabic exercises, quotations, notes, etc. A locket, curious in that it is made of a heavy, dull metal and hangs on a fine chain of steel. When she pressed its spring, it opened and a young woman looked out at her. It is an exquisite painting and she studies it repeatedly. She tells herself she has to get a magnifying glass and look at it properly. The young woman’s hair is blonde and is worn loose and crimped in the style made famous by the Pre-Raphaelites. She has a smooth, clear, brow, an oval face and a delicate chin. Her mouth is about to break into a smile. But her eyes are the strangest shade of blue, violet really, and they look straight at you and they say — they say a lot of things. There’s a strength in that look, a wilfulness; one would almost call it defiance

except that it is so good-humoured. It is the look a woman would wear — would have worn — if she asked a man, a stranger, say, to dance. The date on the back is 1870 and into the concave lid someone had taped a tiny golden key. A calico bag, and inside it, meticulously laundered and with a sachet of lavender tucked between the folds, was a baby’s frock of the finest white cotton, its top a mass of blue and yellow and pink smocking. And folded once, and rolled in muslin, a curious woven tapestry showing a pharaonic image and an Arabic inscription. There was also a shawl, of the type worn by peasant women on special occasions: ‘butter velvet’, white. You can buy one today in the Ghuriyya for twenty Egyptian pounds. And there is another, finer one, in pale grey wool with faded pink flowers — so often worn that in patches you can almost see through the weave.

And there were other things too. Things wrapped in tissue, or in fabric, or concealed in envelopes: a box full of things, a treasure chest, a trunk, actually. It is a trunk.

A story can start from the oddest things: a magic lamp, a conversation overheard, a shadow moving on a wall. For Amal al-Ghamrawi, this story started with a trunk. An old-fashioned trunk made of brown leather, cracked now and dry, with a vaulted top over which run two straps fastened with brass buckles black with age and neglect.

The American had come to Amal’s house. Her name was Isabel Parkman and the trunk was locked in the boot of the car she had hired. Amal could not pretend she was not wary. Wary and weary in advance: an American woman — a journalist, she had said on the phone. But she said Amal’s brother had told her to call and so Amal agreed to see her. And braced herself: the fundamentalists, the veil, the cold peace, polygamy, women’s status in Islam, female genital mutilation — which would it be?

But Isabel Parkman was not brash or strident; in fact she was rather diffident, almost shy. She had met Amal’s brother in New York. She had told him she was coming to Egypt to do a project on the millennium, and he had given her Amal’s

number. Amal said she doubted whether Isabel would come across anyone with grand millennial views or theories. She said that she thought Isabel would find that on the whole everyone was simply worried — worried sick about what would become of Egypt, the Arab countries, ‘le tiers monde’, in the twenty-first century. But she gave her coffee and some names and Isabel went away.