The Magic Christian (11 page)

Read The Magic Christian Online

Authors: Terry Southern

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Humorous, #Fiction Novel

“But

why

did he disappear like that, Guy?” asked Agnes.

“May have moved his offices to another part of the city, you see,” Guy explained, “or out of the city altogether. I know Bill was awfully keen for the West Coast, as a matter of fact; couldn’t get enough of California! Went out there every chance he could.”

“No,

he is not

anywhere

in this country,” said Ginger Horton with considerable authority. “There is absolutely no

trace

of him.”

“Don’t tell me Bill’s chucked the whole thing,” said Grand reflectively, “given it all up and gone off to Bermuda or somewhere.” He gave a soft tolerant chuckle. “Wouldn’t surprise me too much though at that. I know Bill was awfully fond of

fishing

too, come to think of it. Yes, fishing and tennis—that was Bill Thorndike all right.”

“B

UT YOU JUST

cannot

go off like that, Guy,” said Agnes, truly impatient with the boy now when he rose to leave. “Surely you shan’t!”

“Can

and

must,

my dears,” Guy explained, kissing them both. “Flux, motion, growth, change—those are your great life principles. Best keep pace while we can.

He bent forward and took fat Ginger’s hand in his own. “Yes, I’ll be moving on, Ginger,” he said with a warm smile for her, expansive now, perhaps in anticipation, “pushing down to Canaveral and out Los Alamos way!”

“Good Heavens,” said Agnes, “in this dreadful heat? How silly!”

“Always on the go,” purred Esther.

“It’s wise to keep abreast,” said Guy seriously. “I’ll just nip down to Canaveral and see what’s shaking on the space-scene, so to speak.”

“Same old six-and-seven, Guy?” teased big Ginger, flashing up at him.

“Well, who can say?” admitted Guy frankly. “These are odd times—are, if I may say, times that try men’s souls. Yet each of us does his

best

—who can say more?”

“Guy,” said Ginger, squeezing his hand and sparkling up again on one monstrous surge of personality, “it

has

been fun!” Good-byes were her forte.

Guy gave a courtly nod, before turning to go, in deference, it seemed, to her beauty.

“My dear,” he whispered, with a huskiness that made all the ladies tingle, “it has been. . .

inspiring

.”

The S.S.

Magic Christian

was Grand’s last major project—at least it was the last to be brought into open account. After that he began to taper off. However, he did like “keeping in touch,” as he expressed it, and, for one thing, he bought himself a grocery store in New York City. Quite small, it was more or less indistinguishable from the several others in the neighborhood, and Grand put up a little sign in the window.

New Owner—New Policy

Big Get-Acquainted Sale

Grand was behind the counter himself, wearing a sort of white smock—not too unlike his big Vanity lab smock—when the store opened that evening.

His first customer was a man who lived next door to the store. He bought a carton of Grape-Ade.

“That will be three cents,” said Grand.

“How much?”

asked the man, with a frown.

“Three cents.”

“Three

cents?

For six Grape-Ade? Are you kidding?”

“It’s our two-for-one Get-Acquainted on Grape-Ade,” said Grand. “It’s new policy.”

“Boy,

I’ll

say it’s new,” said the man. “And how! Three

cents?

Okay by me, brother!” He slapped three cents on the counter. “There it is!” he said and still seemed amazed when Grand pushed the carton towards him.

“Call again,” said Grand.

“That’s some policy all right,” said the man, looking back over his shoulder as he started for the door. At the door, however, he paused.

“Listen,” he said, “do you sell it . . . uh, you know, by the

case?”

“Well, yes,” said Grand, “you would get some further reduction if you bought it by the case—not too much, of course; we’re working on a fairly small profit-margin during the sale, you see and—”

“Oh, I’ll pay the two-for-one all right. Christ! I just wanted to know if I could

get

a case at that price.”

“Certainly, would you like a case?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I could

use

more than one case . . .”

“How many cases could you use?”

“Well, uh . . . how many . . . how many have you

got?”

“Could you use a thousand?”

“A

thousand?!?

A thousand cases of Grape-Ade?”

“Yes, I could give you say, ten percent off on a thousand and at twenty-four bottles to the case, twelve cents a case would be one hundred and twenty dollars, minus ten percent, would be one hundred and eight call it one-naught-five, shall we?”

“No, no.

I couldn’t use a thousand cases. Jesus! I meant, say,

ten

cases.”

“That would be a dollar twenty.”

“Right!” said the man. He slapped down a dollar twenty on the counter. “Boy, that’s some policy you’ve got there!” he said.

“It’s our Get-Acquainted policy,” said Grand.

“It’s some policy all right,” said the man. “Have you got any other

specials

on? You know, ‘two-for-one,’ that sort of thing?”

“Well, most of our items have been reduced for the Get-Acquainted.”

The man hadn’t noticed it before, but price tags were in evidence, and all prices had been sharply cut: milk, two cents a quart—butter, ten cents a pound—eggs, eleven cents a dozen—and so on.

The man looked wildly about him.

“How about cigarettes?”

“No, we decided we wouldn’t carry cigarettes; since they’ve been linked, rather authoritatively, to cancer of the lung, we thought it wouldn’t be exactly in the best of taste to sell them—being a

neighborhood

grocery, I mean to say.”

“Uh-huh, well—listen, I’m just going home for a minute now to get a sack, or a . . . trunk, or maybe a truck . . . I’ll be right back . . .”

Somehow the word spread through the neighborhood and in two hours the store was clean as a whistle.

The next day, a sign was on the empty store:

MOVED TO NEW LOCATION

And that evening, in another part of town, the same thing occurred—followed again by a quick change of location. The people who had experienced the phenomenon began to spend a good deal of their time each evening looking for the new location. And occasionally now, two such people meet—one who was at the big Get-Acquainted on West 4th Street, for example, and the other at the one on 139th—and so, presumably, they surmise not only that it wasn’t a dream, but that it’s still going on.

And some say it does, in fact, still go on—they say it accounts for the strange searching haste which can be seen in the faces, and especially the eyes, of people in the cities, every evening, just about the time now it starts really getting dark.

A Biography of Terry Southern

Terry Southern (1924–1995) was an American satirist, author, journalist, screenwriter, and educator and is considered one of the great literary minds of the second half of the twentieth century. His bestselling novels—

Candy

(1958), a spoof on pornography based on Voltaire’s

Candide

, and

The Magic Christian

(1959), a satire of the grossly rich also made into a movie starring Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr—established Southern as a literary and pop culture icon. Literary achievement evolved into a successful film career, with the Academy Award–nominated screenplays for

Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

(1964), which he wrote with Stanley Kubrick and Peter George, and

Easy Rider

(1969), which he wrote with Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper.

Born in Alvarado, Texas, Southern was educated at Southern Methodist University, the University of Chicago, and Northwestern, where he earned his bachelor’s degree. He served in the Army during World War II, and was part of the expatriate American café society of 1950s Paris, where he attended the Sorbonne on the GI Bill. In Paris, he befriended writers James Baldwin, James Jones, Mordecai Richler, and Christopher Logue, among others, and met the prominent French intellectuals Jean Cocteau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus. His short story “The Accident” was published in the inaugural issue of the

Paris Review

in 1953, and he became closely identified with the magazine’s founders, Harold L. Humes, Peter Matthiessen and George Plimpton, who became his lifelong friends. It was in Paris that Southern wrote his first novel,

Flash and Filigree

(1958), a satire of 1950s Los Angeles.

When he returned to the States, Southern moved to Greenwich Village, where he took an apartment with Aram Avakian (whom he’d met in Paris) and quickly became a major part of the artistic, literary, and music scene populated by Larry Rivers, David Amram, Bruce Conner, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac, among others. After marrying Carol Kauffman in 1956, he settled in Geneva until 1959. There he wrote

Candy

with friend and poet Mason Hoffenberg, and

The Magic Christian

. Carol and Terry’s son, Nile, was born in 1960 after the couple moved to Connecticut, near the novelist William Styron, another lifelong friend.

Three years later, Southern was invited by Stanley Kubrick to work on his new film starring Peter Sellers, which became,

Dr. Strangelove

.

Candy

, initially banned in France and England, pushed all of America’s post-war puritanical buttons and became a bestseller. Southern’s short pieces have appeared in the

Paris Review

,

Esquire

, the

Realist

,

Harper’s Bazaar

,

Glamour

,

Argosy

,

Playboy

, and the

Nation

, among others. His journalism for

Esquire

, particularly his 1962 piece “Twirling at Ole Miss,” was credited by Tom Wolfe for beginning the New Journalism style. In 1964 Southern was one of the most famous writers in the United States, with a successful career in journalism, his novel

Candy

at number one on the

New York Times

bestseller list, and

Dr. Strangelove

a hit at the box office.

After his success with

Strangelove

, Southern worked on a series of films, including the hugely successful

Easy Rider

. Other film credits include

The Loved One

,

The Cincinnati Kid

,

Barbarella

, and

The End of the Road

. He achieved pop-culture immortality when he was featured on the famous album cover of the Beatles’

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

. However, despite working with some of the biggest names in film, music, and television, and a period in which he was making quite a lot of money (1964–1969), by 1970, Southern was plagued by financial troubles.

He published two more books:

Red-Dirt Marijuana and Other Tastes

(1967), a collection of stories and other short pieces, and

Blue Movie

(1970), a bawdy satire of Hollywood. In the 1980s, Southern wrote for

Saturday Night Live,

and his final novel,

Texas Summer

, was published in 1992. In his final years, Southern lectured on screenwriting at New York University and Columbia University. He collapsed on his way to class at Columbia on October 25, 1995, and died four days later.

The Southern home in Alvarado, Texas, seen here in the 1880s.

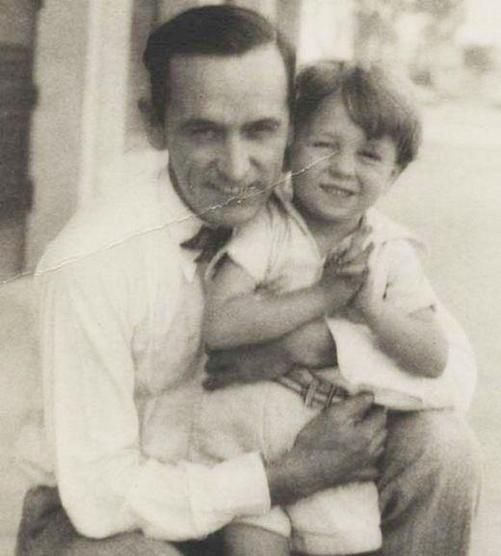

A young Southern with a dog in Alvarado, his hometown, around 1929.