The Lord of the Rings (190 page)

Read The Lord of the Rings Online

Authors: J. R. R. Tolkien

Tags: #Middle Earth (Imaginary place), #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #General, #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Literary Criticism, #Baggins; Frodo (Fictitious character), #Epic, #Fantasy Fiction; English

Note that consonants written twice, as

tt

,

ll

,

ss

,

nn

, represent long or ‘double’ consonants. At the end of words of more than one syllable these were usually shortened: as in

Rohan

from

Rochann

(archaic

Rochand

).

In Sindarin the combinations

ng

,

nd

,

mb

, which were specially favoured in the Eldarin languages at an earlier stage, suffered various changes,

mb

became

m

in all cases, but still counted as a long consonant for purposes of stress (see below), and is thus written

mm

in cases where otherwise the stress might be in doubt.

ng

remained unchanged except finally where it became the simple nasal (as in English

sing

).

nd

became

nn

usually, as

Ennor

‘Middle-earth’, Q.

Endóre

; but remained

nd

at the end of fully accented monosyllables such as

thond

‘root’ (cf.

Morthond

‘Blackroot’), and also before

r

, as

Andros

‘long-foam’. This

nd

is also seen in some ancient names derived from an older period, such as

Nargothrond

,

Gondolin

,

Beleriand

. In the Third Age final

nd

in long words had become

n

from

nn

, as in

Ithilien

,

Rohan

,

Anorien

.

VOWELS

For vowels the letters

i, e, a, o, u

are used, and (in Sindarin only)

y

. As far as can be determined the sounds represented by these letters (other than

y

) were of normal kind, though doubtless many local varieties escape detection. That is, the sounds were approximately those represented by

i, e, a, o, h

in English

machine

,

were, father, for, brute,

irrespective of quantity.

In Sindarin long

e, a, o

had the same quality as the short vowels, being derived in comparatively recent times from them (older

é, á, ó

had been changed). In Quenya long

ę

and

ó

were, when correctly pronounced, as by the Eldar, tenser and ‘closer’ than the short vowels.

Sindarin alone among contemporary languages possessed the ‘modified’ or fronted

u

, more or less as

u

in French

lune

. It was partly a modification of

o

and

u

, partly derived from older diphthongs

eu

,

iu

. For this sound

y

has been used (as in ancient English): as in

lyg

‘snake’, Q.

leuca

, or

emyn

pl. of

amon

‘hill’. In Condor this

y

was usually pronounced like

i

.

Long vowels are usually marked with the ‘acute accent’, as in some varieties of Fëanorian script In Sindarin long vowels in stressed monosyllables are marked with the circumflex, since they leaded in such cases to be specially prolonged; so in

dűn

compared with

Dúnadan

. The use of the circumflex in other languages such as Adűnaic or Dwarvish has no special significance, and is used merely to mark these out as alien tongues (as with the use of

k

).

Final

e

is never mute or a mere sign of length as in English. To mark this final

e

it is often (but not consistently) written

ë

.

The groups

er, ir, ur

(finally or before a consonant) are not intended to be pronounced as in English

fern, fir, fur,

but rather is English

air. eer, oor

.

In Quenya

ui, oi, ai

and

iu, eu, au

are diphthongs (that is, pronounced in one syllable). All other pairs of vowels are dis-syllabic. This is often indicated by writing

ëa, ëo, oë

.

In Sindarin the diphthongs are written

ae, oi, ei, oe, ui,

and

au

. Other combinations are not diphthongal. The writing of final

au

as

aw

is in accordance with English custom, but is actually not uncommon in Fëanorian spellings.

All these diphthongs were falling diphthongs, that to stressed on the first element, and composed of the simple vowels run together. Thus

ai, ei, oi, ui

are intended to be pronounced respectively as the vowels in English

rye

(not

ray

),

grey, boy, ruin

: and

au

(

aw

) as in

loud, how

and not as in

laud, haw

.

There is nothing in English closely corresponding to

ae, oe, eu

;

ae

and

oe

may be pronounced as

ai, oi

.

STRESS

The position of the ‘accent’ or stress is not marked, since in the Eldarin languages concerned its place is determined by the form of the word. In words of two syllables it falls in practically all cases on the first syllable. In longer words it falls on the last syllable but one, where that contains a long vowel, a diphthong, or a vowel followed by two (or more) consonants. Where the last syllable but one contains (as often) a short vowel followed by only one (or no) consonant, the stress falls on the syllable before it, the third from the end. Words of the last form are favoured in the Eldarin languages, especially Quenya.

In the following examples the stressed vowel is marked by a capital letter:

isIldur

,

Orome

,

erEssëa

,

fËanor

,

ancAlima

,

elentÁri

;

dEnethor

,

periAnnath

,

ecthElion

,

pelArgir

,

silIvren

. Words of the type

elentÁri

‘star-queen’ seldom occur in Quenya where the vowel is

é, á, ó,

unless (as in this case) they are compounds; they are commoner with the vowels

í, ú,

as

andÚne

‘sunset, west’. They do not occur in Sindarin except in compounds. Note that Sindarin

dh, th, ch

are single consonants and represent single letters in the original scripts.

NOTE

In names drawn from other languages than Eldarin the same values for the letters are intended, where not specially described above, except in the case of Dwarvish. In Dwarvish, which did not possess the sounds represented above by

th

and

ch

(

kh

),

th

and

kh

are aspirates, that is

t

or

k

followed by an

h

, more or less as in

backhand

,

outhouse

.

Where

z

occurs the sound intended is that of English

z

.

gh

in the Black Speech and Orcish represents a ‘back spirant’ (related to

g

as

dh

to

d

); as in

ghâsh

and

agh

.

The ‘outer’ or Mannish names of the Dwarves have been given Northern forms, but the letter-values are those described. So also in the case of the personal and place-names of Rohan (where they have not been modernised), except that here

éa

and

éo

are diphthongs, which may be represented by the

ea

of English

bear

, and the

eo

of

Theobald

;

y

is the modified

u

. The modernised forms are easily recognised and are intended to be pronounced as in English. They are mostly place-names: as Dunharrow (for

Dúnharg

), except Shadowfax and Wormtongue.

II. WRITING

The scripts and letters used in the Third Age were all ultimately of Eldarin origin, and already at that time of great antiquity. They had reached the stage of full alphabetic development, but older modes in which only the consonants were denoted by full letters were still in use.

The alphabets were of two main, and in origin independent kinds: the

Tengwar

or

Tîw

, here translated as ‘letters’; and the

Certar

or

Cirth,

translated as ‘runes’. The

Tengwar

were devised for writing with brush or pen, and the squared forms of inscriptions were in their case derivative from the written forms. The

Certar

were devised and mostly used only for scratched or incised inscriptions.

The

Tengwar

were the more ancient; for they had been developed by the Noldor, the kindred of the Eldar most skilled in such matters, long before their exile. The oldest Eldarin letters, the Tengwar of Rúmil, were not used in Middle-earth. The later letters, the Tengwar of Fëanor, were largely a new invention, though they owed something to the letters of Rúmil. They were brought to Middle-earth by the exiled Noldor, and so became known to the Edain and Númenóreans. In the Third Age their use had spread over much the same area as that in which the Common Speech was known.

The Cirth were devised first in Beleriand by the Sindar, and were long used only for inscribing names and brief memorials upon wood or stone. To that origin they owe their angular shapes, very similar to the runes of our times, though they differed from these in details and were wholly different in arrangement. The Cirth in their older and simpler form spread eastward in the Second Age, and became known to many peoples, to Men and Dwarves, and even to Orcs, all of whom altered them to suit their purposes and according to their skill or lack of it. One such simple form was still used by the Men of Dale, and a similar one by the Rohirrim.

But in Beleriand, before the end of the First Age, the Cirth, partly under the influence of the Tengwar of the Noldor, were rearranged and further developed. Their richest and most ordered form was known as the Alphabet of Daeron, since in Elvish tradition it was said to have been devised by Daeron, the minstrel and loremaster of King Thingol of Doriath. Among the Eldar the Alphabet of Daeron did not develop true cursive forms, since for writing the Elves adopted the Fëanorian letters. The Elves of the West indeed for the most part gave up the use of runes altogether. In the country of Eregion, however, the Alphabet of Daeron was maintained in use and passed thence to Moria, where it became the alphabet most favoured by the Dwarves. It remained ever after in use among them and passed with them to the North. Hence in later times it was often called

Angerthas Moria

or the Long Rune-rows of Moria. As with their speech the Dwarves made use of such scripts as were current and many wrote the Fëanorian letters skilfully; but for their own tongue they adhered to the Cirth, and developed written pen-forms from them.

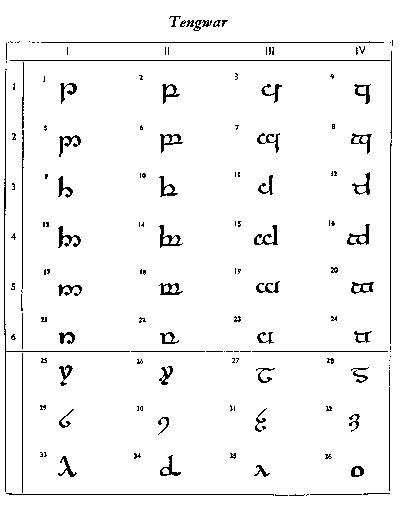

(i) THE FËANORIAN LETTERS

The table shows, in formal book-hand shape, all the letters that were commonly used in the West-lands in the Third Age. The arrangement is the one most usual at the time, and the one in which the letters were then usually recited by name.

This script was not in origin an ‘alphabet’, that is, a haphazard series of letters, each with an independent value of its own, recited in a traditional order that has no reference either to their shapes or to their functions. It was, rather, a system of consonantal signs, of similar shapes and style, which could be adapted at choice or convenience to represent the consonants of languages observed (or devised) by the Eldar. None of the letters had in itself a fixed value; but certain relations between them were gradually recognised.

The system contained twenty-four primary letters, 1-24, arranged in four

témar

(series), each of which had six

tyeller

(grades). There were also ‘additional letters’, of which 25-36 are examples. Of these 27 and 29 are the only strictly independent letters; the remainder are modifications of other letters. There was also a number of

tehtar

(signs) of varied uses. These do not appear in the table.

The

primary letters

were each formed of a

telco

(stem) and a

lúva

(bow). The forms seen in 1-4 were regarded as normal. The stem could be raised, as in 9-16; or reduced, as in 17-24. The bow could be open, as in Series I and III; or closed, as in II and IV; and in either case it could be doubled, as e.g. in 5-8.

The theoretic freedom of application had in the Third Age been modified by custom to this extent that Series I was generally applied to the dental or

t

-series (

tincotéma

), and II to the labials or

p

-series (

parmatéma

). The application of Series III and IV varied according to the requirements of different languages.