The Living Reed: A Novel of Korea (63 page)

Read The Living Reed: A Novel of Korea Online

Authors: Pearl S. Buck

The crumpled paper had fallen from his hand. He saw it lying there and took it up and smoothed it out, and read it again.

“Are you living?” These were the words. She had sent them in jest perhaps, or perhaps in love. Safe enough, those words she had chosen by accident, perhaps, in a mood of gaiety or loneliness. Then suddenly conviction rose in him like a voice, though he heard no voice.

Are you living?

Living! His uncle was the Living Reed. Even as he lay in his grave people had murmured the words, and some told again the legend of the young bamboo pushing up between the rough stones in the cell from which he had escaped so long ago. From his coffin he could not escape, and the people mourned. But only a few days ago, Liang now remembered, his uncle had reminded him, almost shyly, of his return one night in secret to see his younger brother, and of how he, Liang, then a baby, had seemed to recognize him, although they had never met before.

“You sprang into my arms, you put your hands upon my cheeks, you knew me from some other life—”

He could almost remember the moment itself. And he recalled other times when Yul-chun had talked of the heritage of Korean patriots.

“In the spring,” he could hear his uncle saying, “in the spring the old root of the bamboo sends up its new green shoot. It has always been so and it will be so forever, as long as men are born.”

“… Come into the house,” his grandmother was calling. “Come into the house, Liang, and shut the door!”

He rose and went no further than the door. He stood there, himself again.

“I am going to the city, Grandmother. Grandfather, I must ask my friend to send a message for me—my American friend.”

“What message?” Il-han asked.

“That I am living,” Liang said.

“It is late,” Sunia complained.

“Not too late, Grandmother,” he said, “not while I live.”

And bowing to them he left them to Ippun and went his way alone. In the sky beyond the gate a new young moon held fullness, and beneath the moon there shone a star, the usual, steady star.

I

T WAS HIGH NOON

at Pusan, on a fine autumn day, two years ago. I had traveled the length and breadth of South Korea, by motorcar, so that I could stop when I liked. The road was often narrow and rough, the bridges over the many brooks, bombed during the war, had not yet been rebuilt, and we rattled over dry stones or splashed through water made shallow by the dry season. I had enjoyed all of it, marveling afresh at the noble beauty of the landscape and treasuring afresh the warm welcoming kindness of the people. Now I was at Pusan, at the southern tip of Korea. It is a port famous in history, but I had not come here for the sake of history. I had come to visit the place where men of the United Nations who died in the Korean war lie buried, each nationality under its own flag. In the cool autumn wind all the flags were flying bravely.

I laid the wreath I had brought at the foot of the memorial monument and I stood for a few minutes of contemplative silence. The scene was matchless. On three sides was the surrounding sea, a sea as blue as the Mediterranean. Behind were the severe gray flanks of the mountains, the town nestled at their feet. The cemetery is as beautiful as a garden, kept meticulously by devoted Koreans. On either side of me stood two young Korean guards in military uniform, silent as I surveyed the scene. My eyes rested on the American flag.

“I would like to walk among the graves of the Americans,” I said. “I knew some of them.”

The guard on my right replied, “Madame, we are very sorry—no Americans are here. All were returned to your country. Only the flag remains.”

I had a feeling of shock. No Americans here? How this must have wounded the Koreans! Before I could express my regret, a tall Korean man in a western business suit approached me. The brilliant sun shone on his silver-gray hair, his handsome intelligent face. He spoke in English.

“Do not be distressed, please. We understand how the families of the brave Americans might feel. It is only natural that they wished to have their sons safely home again. Our country must seem a very remote place in which to die.”

“Thank you,” I replied. “All the same, I believe that if my fellow countrymen had known, had understood, they would have been honored to leave their sons here, among their comrades.”

“Ah yes,” a soft voice put in. “I have been in your country—I know how friendly your people are.”

“My wife,” the tall Korean said.

I turned and met face to face an exquisite woman in Korean dress.

It was the beginning of a friendship and from these two I created the characters of Liang and Mariko. From them also I learned what happened after the ending of my book. I had read, of course, of the events, how the American government had done its best to correct the first misunderstandings. But through my new Korean friends I came to my own comprehension of all that had happened.

“We misunderstood, too,” Liang said one night, a week later, as we lingered over dinner in his house in Seoul. “Koreans were angry and disappointed when the first Americans came. I am sure that your soldiers during the days of the occupation, in those years between 1945 and 1948, must have had many bad experiences. We were not at our best after half a century of ruthless Japanese control.”

“Even the Japanese did some good things,” Mariko reminded him. “Don’t forget your hospital.”

We were sitting on the warm ondul floor around the low table. It was a pleasant room in a delightful house, Korean but modern. Next door was the excellent hospital where Liang worked. He had done graduate work at Johns Hopkins and was a skilled surgeon.

“I remember the good as well as the evil,” he now replied, and went on: “But we Koreans are determined to be a free and independent nation. We will never give up that struggle. It is in the beat of our hearts, in the flow of our blood. And we look back and wonder how different our lives might have been if that treaty between our two countries, yours and mine, had been honored—that treaty of amity and commerce, ratified by your country in 1883, that gave us the promise of your assistance if we were invaded. In return we were to give you our trade. But your Theodore Roosevelt was prudent—he did not wish to become embroiled in the rivalry of Japan and Russia for possession of Korea. William Howard Taft, who was then your Secretary of War, went to Tokyo and on July 29, 1905, signed a secret agreement giving Korea to Japan, if Japan would promise not to keep your country out of Manchuria and not to attack the Philippines—”

Mariko rose from the table. “Liang, why do you speak of old things? Let us speak of how Americans sent their sons here to die for our freedom.”

Liang responded instantly. “Yes! You are right.”

We all rose then and went into the living room and Mariko played the piano and she and Liang sang together, most beautifully, old Korean songs and new American songs. I remember they sang a duet version of “Getting to Know You” from the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical.

Looking back, I know that both Liang and Mariko were right. Yes, the mistakes of history bring relentless reprisals. There is a direct connection between that secret agreement signed in Tokyo by Taft and Katsura and the young men of many nations who died on Korean soil. Korea is divided today not only by the 38th parallel, but also by the Korean men and women born in Russian territory when their parents fled their country at the time it was occupied by Japan. These children grew up in Communism, as Sasha did, and believed they were “liberating” their country when they went to Korea. American lads died at their hands.

But, as Mariko says, why speak of old things? Let us remember, rather, that a tie binds our peoples together. Brave young American men climbed the rugged slopes of Korean mountains and fought in homesickness and desperate weariness for the sake of a people strange to them and for reasons they scarcely understood, even when they yielded up their lives. With such noble impulse and final sacrifice, let the past be forgot, except for what it teaches for the future.

PEARL S. BUCKA Biography of Pearl S. Buck

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973) was a bestselling and Nobel Prize-winning author of fiction and nonfiction, celebrated by critics and readers alike for her groundbreaking depictions of rural life in China. Her renowned novel

The Good Earth

(1931) received the Pulitzer Prize and the William Dean Howells Medal. For her body of work, Buck was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Literature—the first American woman to have won this honor.

Born in 1892 in Hillsboro, West Virginia, Buck spent much of the first forty years of her life in China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries based in Zhenjiang, she grew up speaking both English and the local Chinese dialect, and was sometimes referred to by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhju. Though she moved to the United States to attend Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, she returned to China afterwards to care for her ill mother. In 1917 she married her first husband, John Lossing Buck. The couple moved to a small town in Anhui Province, later relocating to Nanking, where they lived for thirteen years.

Buck began writing in the 1920s, and published her first novel,

East Wind: West Wind

in 1930. The next year she published her second book,

The Good Earth

, a multimillion-copy bestseller later made into a feature film. The book was the first of the Good Earth trilogy, followed by

Sons

(1933) and

A House Divided

(1935). These landmark works have been credited with arousing Western sympathies for China—and antagonism toward Japan—on the eve of World War II.

Buck published several other novels in the following years, including many that dealt with the Chinese Cultural Revolution and other aspects of the rapidly changing country. As an American who had been raised in China, and who had been affected by both the Boxer Rebellion and the 1927 Nanking Incident, she was welcomed as a sympathetic and knowledgeable voice of a culture that was much misunderstood in the West at the time. Her works did not treat China alone, however; she also set her stories in Korea (

Living Reed

), Burma (

The Promise

), and Japan (

The Big Wave

). Buck’s fiction explored the many differences between East and West, tradition and modernity, and frequently centered on the hardships of impoverished people during times of social upheaval.

In 1934 Buck left China for the United States in order to escape political instability and also to be near her daughter, Carol, who had been institutionalized in New Jersey with a rare and severe type of mental retardation. Buck divorced in 1935, and then married her publisher at the John Day Company, Richard Walsh. Their relationship is thought to have helped foster Buck’s volume of work, which was prodigious by any standard.

Buck also supported various humanitarian causes throughout her life. These included women’s and civil rights, as well as the treatment of the disabled. In 1950, she published a memoir,

The Child Who Never Grew

, about her life with Carol; this candid account helped break the social taboo on discussing learning disabilities. In response to the practices that rendered mixed-raced children unadoptable—in particular, orphans who had already been victimized by war—she founded Welcome House in 1949, the first international, interracial adoption agency in the United States. Pearl S. Buck International, the overseeing nonprofit organization, addresses children’s issues in Asia.

Buck died of lung cancer in Vermont in 1973. Though

The Good Earth

was a massive success in America, the Chinese government objected to Buck’s stark portrayal of the country’s rural poverty and, in 1972, banned Buck from returning to the country. Despite this, she is still greatly considered to have been “a friend of the Chinese people,” in the words of China’s first premier, Zhou Enlai. Her former house in Zhenjiang is now a museum in honor of her legacy.

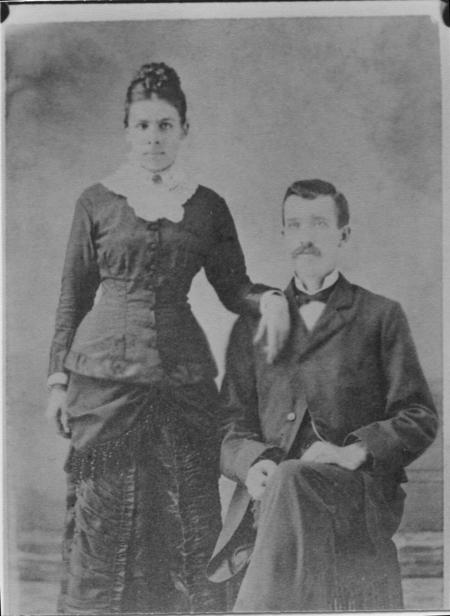

Buck’s parents, Caroline Stulting and Absalom Sydenstricker, were Southern Presbyterian missionaries.

Buck was born Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker in Hillsboro, West Virginia, on June 26, 1892. This was the family’s home when she was born, though her parents returned to China with the infant Pearl three months after her birth.