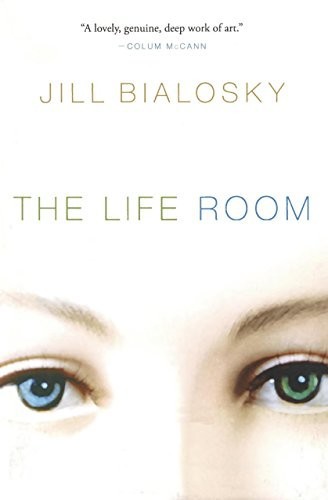

The Life Room

Authors: Jill Bialosky

Copyright © 2007 by Jill Bialosky

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Excerpts from this book were previously published in

Bomb

and

Open City

.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Bialosky, Jill.

The life room/Jill Bialosky.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Self-realization—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3552.I19L54 2007

813'.54—dc22 2006038236

ISBN

978-0-15-101047-9

ISBN

978-0-15-603432-6 (pbk.)

e

ISBN

978-0-544-59916-1

v1.1214

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, organizations, and events are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

“Where am I? What am I doing? Why?”

—From

Anna Karenina

by Leo Tolstoy

1

She had been born with different colored eyes. One blue and the other green. When she looked at herself in the mirror, she felt as if she were split down the center, divided, as if one part of her were competing with the other. She had heard that if a person has dissimilar eyes at birth, it is quite possible that the two eyes were subjected to different pressures within the womb.

Tonight she felt as if her blue eye was telling her to go to Paris and her green eye was telling her not to go. She had just been invited to give a paper on Tolstoy at an international conference on world literature at the Sorbonne and, of course, she had to go; it was an honor, something she had long hoped for. She loved the exhilaration that followed after presenting a paper. She imagined herself walking through the Parisian city streets and sitting in cafés, hearing stimulating lectures by academics she admired. She imagined she’d find both the quiet time and the inspiration she needed to begin turning the paper she had written on

Anna Karenina

into a full-length study. The thought of going filled her with guilty pleasure. But she did not want to think about leaving her family behind. She could not bear being separated from them. She knew it was irrational, yet she often experienced feelings that on one level seemed irrational and on another felt perfectly reasonable. Now she was in bed, glad that Michael had drifted off. She hadn’t told him yet about Paris, not because she chose to keep secrets. She only wanted to keep her trip to herself for as long as possible, to revel in her accomplishment privately. She didn’t want her own thoughts to escape before she’d had a chance to digest them.

Eleanor listened to the creaks in the wood, the bang of the radiator. The boys were sound asleep in the room across the hall from them, and Michael was breathing in lightly, making a whistling sound through his nose. Suddenly, Eleanor was so frightened by the thought of leaving them that she couldn’t move. She said to herself,

It’s okay. Nothing is going to happen to the boys or Michael if you go away. They’ll be here waiting. Go see your boys

. She rose from the bed and moved into the room where the boys slept and slipped in next to Noah, the youngest, and held him. She fell asleep again, and when she awoke it was dawn. She crept down the drafty hall, folded her body underneath the sheet in the bed next to her husband, and fell back to sleep.

First it was Noah she heard rustle in the bed across the hall, the patter of his bare feet on the wood as he turned the corner to the bathroom, the creak of the toilet seat lifting—he remembered this time. She heard his small feet running back into his bedroom. Light began to filter through her open window, and the morning released its crisp smell into the air. It was the weekend, and time had slowed down just a morsel, so that she could feel everything around her more intensely. She watched the light slowly strengthen in the room, the colors of the walls shimmering. Soon she heard Noah and Nicholas. They were whispering in their beds, no doubt hatching a plan.

Michael was turned into the corner of the antique bed, the sheets reaching across his broad shoulders. She felt his hand reach across her middle. It was warm and she allowed him to pull her against him. She had awoken to his particular smell for over twelve years. And each morning she took it in newly, never tiring of the comfort and warmth of his body beside her. She nestled her head into the back of his neck. He wasn’t quite awake, and it was in this half-conscious state that he always wanted to hold her first, as if he needed her body to rouse him before he took in any more of the world. This desire to see life through her eyes was what she found so endearing about him from the first day they met. She remembered how he had wanted to share every minute with her, so that going to the store to shop for dinner was an adventure. He took her by the hand through the aisles to the most secluded spot in the store where he could embrace her, until they felt an urgent desire to return to either her studio apartment or his. It did not matter whether they had much in common to talk about. She was in awe of all the ways in which he was different from her, so that together they seemed to make a neat package of contradictions.

If only she could hold this moment of reflection longer and stop time from moving forward. She was already aware of how quickly the morning would be consumed by the obligations that awaited her, but when the boys flew into the room, bounding on top of the bed with their plastic swords and reenacting a duel from

Star Wars

, she laughed. Michael continued to feign sleep while they poked him with their swords, then came to life in a roar. The boys came tumbling down on top of them, forcing Eleanor and Michael to make room for them.

“I was invited to Paris,” she whispered, curling up against Michael’s sleep-filled body after the boys had run out of their bedroom with their swords. To release her anxiety, she told Michael about her paper’s acceptance in a voice intimate and private, wanting him to share in her enthusiasm.

“That’s terrific,” he said, turning over to look at her, “But Paris? For how long? Are you sure you want to go so far away without us?”

His reaction deflated the excitement she had been carrying around with her for nearly twenty-four hours and made her more anxious. In his reaction she read her own fears. She explained the significance of being asked to participate in the conference, how it would be an added asset to her vita, an important place to make connections. She did not want to tell him that lately—when she’d learned a colleague had just published a new book or someone she knew had gotten tenure—she felt panicked, as if time was racing by without her.

“But it’s not something you have to do?” Michael said, yawning.

“If you don’t want me to go, just say it,” she said, rising from her pillow. She nearly hated this part of him that could not fully accept that she had ambitions separate from his. She had wanted him to encourage her to go, to tell her that they’d be fine without her, that it was an honor she couldn’t refuse. “I haven’t gone away for more than a weekend conference since Nicholas was born.”

“Of course I want you to go.” He pulled her closer to the warmth of his body as if claiming power over her. “If leaving us is what you want to do.”

“I don’t want to leave you.”

“I know,” Michael said, his voice still not quite awake.

Michael Gordon was a heart surgeon affiliated with a research hospital. He acted rather than pondered. He went in and fixed things. He cut open the chest, parted the walls of the thoracic cavity, inserted tubes to initiate heart-lung bypass, and then placed grafts into the blocked arteries. Often, after the boys were in bed, he looked at biopsies of animal heart muscle for a research project he was involved in on the regeneration of damaged hearts. Other times he reviewed laboratory results and images of carotid studies.

They had met at a wedding of mutual friends. Eleanor was an assistant professor at Columbia and Michael was doing his residency. They ended up in the lobby of the Plaza, both having ducked out before the dancing (they were at the age where it was depressing to be at a wedding if you were unattached), and shared a cab. “I noticed your eyes at dinner,” Michael said. His were surrounded by tortoiseshell glasses. Eleanor had grown used to people staring at hers. The two different colors had a hypnotic effect, as if people wanted to be drawn in closer, to see more when they looked at her. Or perhaps people were drawn to the unfamiliar. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a person with that particular mutation. It’s always been textbook.” He looked at her more closely Sometimes the bluer eye seemed softer, other times the green eye, so that it was often difficult to read her.

He had walked Eleanor to the door of her building, and they continued talking on the front steps. “Why did you want to be a heart surgeon?” She studied his cleanly shaven face, catching a whiff of his expensive cologne. She noticed his pressed Brooks Brothers suit and conservative tie; his stiff, practical leather shoes. She was used to academics, writers, and artists, who dressed more casually. She studied him more closely. His fingernails were cut short and square. His hands were rough from washing and scrubbing. He spoke in short sentences. He listened. He was tall and broad and athletic looking. His thick brown hair was slicked back off his face. He had nice sideburns, perfectly in line with his jawbone. He was handsome in a boyish way. It was 95°, one of those saunalike August days in New York. “Don’t you want to undo your tie?” she said, looking at him as sweat dripped down his face. She had the urge to mess him up.

He told her about his training, how he had learned to distance himself from the organs in the body, to view them as pathology specimens. But once he’d held a still-beating heart in his hand. “The heart is the only organ that functions outside the body. It contains its own spontaneous activity. That’s why poets and philosophers have proclaimed it the place in the body where we feel things.” Sitting on the stoop, they were at eye level, but she could not quite see into his eyes through the lenses of his glasses, and this troubled her. He tucked his hand inside the lip of her blouse above her breast and rested it over her heart. It was beating so strongly she thought it was pulsing out of her chest into his hand. “This is what I do,” he said. “This is what I take care of.”

Every day there was something new to admire about him. Some people are perpetually late and others are perpetually on time. He was always at the proposed meeting place precisely when he said he would be there. He was a man of his word. He was organized and focused. He knew exactly what he wanted out of life. His constitution was as structurally sound as a building. She found in his presence that her inner clock began to steady. She didn’t have to try to numb herself so that she would not feel so deeply. Michael was easy and soothing. He didn’t question her constantly or demand so much of her attention. She felt she had more room to be herself. He liked to run, sometimes five or six miles in the park, and when he returned he was more energetic than when he had left. She wondered what he thought of when he ran, what absorbed his attention when it wasn’t the activity at hand. Once she asked, and he said he counted his paces. They married a year after they’d met. They settled into their life together, and Eleanor learned to adjust to his practical, more reserved nature. It wasn’t that he didn’t look for the underside, it was that he put his feelings in perspective. His disposition had the effect of balancing out Eleanor’s moodiness, but she found herself keeping some of her thoughts to herself. Sometimes she wished he would let go and be more spontaneous and adventurous.