The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (52 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

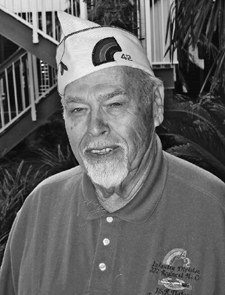

Frederick “Fritz” Krenkler

Though his wife stayed with him, Fritz Krenkler’s explosions destroyed his relationship with two of his three children. “Two of them to this day won’t have anything to do with me. Makes me very sad because it’s a big hurt. And my oldest girl has cancer, and that makes me sad. I carried a package—but we all carried a package. I was not alone, that’s the big thing. I was even not as bad as some of them.”

Half a century after the war, he finally found a private therapist who could help him—mostly, he says, by letting him rant and rave. The therapist told him to let it out. “And this was the thing that was bottled up much, much too long.”

What he hasn’t done is talk to his buddies, the guys he survived the war with, and tell them how therapy helped. As we sat in a corner at the Mobile, Alabama, hotel where the men of the Rainbow were having their reunion, Fritz said, “This has been very private—as a matter of fact, you’re one of the first strangers I’ve mentioned it to.”

I said. “You did it because I pushed.”

And he responded, “Whether you did or not, it’s because I wanted to answer.”

Or maybe because it took only sixty-three years for a stranger to ask.

It wasn’t called post-traumatic stress disorder in 1945, and, like the GIs who later returned from battlefields in Korea, Vietnam, the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq, the soldiers who came home from World War II, for the most part, just wanted to get on with their lives. Without official acknowledgment that combat messes with your head in a way that leaves invisible unhealed wounds, they were unlikely to seek help. And even sixty-five years later, they’re still having the occasional nightmare and flashback to their war years. But, as Harry Feinberg was forced to acknowledge, the ones who still survive have fewer buddies to call, to talk it through with. They know a soldier’s truth about war that those who’ve never been there will never know: a war doesn’t end just because some general signed a piece of paper. In some respects, for some, wars never end.

The postwar stories you’ve just read from the soldiers who fought in World War II are not meant to be perceived as museum library contributions—little pieces of oral history that have no present-day application. What these men have gone through, and are still going through, should be recognized by everyone, ordinary citizens and especially our elected officials, as part of the price that’s paid for going to war. The man or woman we send to war is not the same man or woman we get back. War is not that simple, that easy. If it didn’t change those who experience it, we should be very worried about the kind of young people our civilization is producing. What we must do as a nation to help our veterans readjust is learn to write the check to beef up postwar health services at the same moment as we dispatch the first planeload or shipload of soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, or coastguardmen.

Aside from letting your representatives in Congress and the president know how you feel about providing better-than-barely-adequate support for veterans, what’s the message for you, the nonveteran reading this book? It’s simple: if you know any veterans who have been lucky enough to come back from his or her war—whether World War II, one we are currently fighting, or any in between—do a good deed: ask them to tell you about their wartime experiences. If they hesitate, tell them you can handle what they have to say. And then pay close attention, really listen, no matter how difficult or emotional it becomes.

A memorial in the garden of the Hebrew Educational Alliance, a Denver Conservative synagogue, dedicated to the men of the 157th Infantry Regiment and to “all who liberated prisoners from Nazi concentration camps.”

If they turn you down once, ask again another day. Our veterans need to know that we support them, that we care. One of the best ways for an individual to do that is to explain that you want to know about their service to our country, that it’s important that we all know. It’s a demonstrably useful way to honor their service. No veteran should have to wait fifty years to be able to tell someone about it. You won’t regret that you asked.

And don’t put it off, especially with veterans of World War II. As Jim Bird, who was at Dachau with the 45th Infantry Division, warns, “Most of us are on the ‘slippery slope’ of life, and the leaves are falling every day.”

U.S. Army Signal Corps newsreel footage of the liberation of many concentration camps has been made available online at the Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Many of the scenes described in this book can be seen in this newsreel collection.

At the same site, you can access thousands of Holocaust-related photos from the National Archives as well as from private donors that the USHMM has digitized and made available in a searchable online catalog. Go to

www.ushmm.org/research/collections/search/

.

If you find the USHMM collections useful, you might want to consider making a contribution and/or becoming a member. Your financial support will help the USHMM continue this worthwhile work. You might also consider supporting Holocaust museums and educational centers situated elsewhere in the United States or the world.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to offer the largest possible measure of gratitude to the veterans who agreed to talk with me about the World War II experiences that brought them face-to-face with the Holocaust. Because they were willing to relive the unbelievable, future generations who, sadly, will not have the opportunity to hear from them directly will still have an opportunity to study the words of these courageous men and women who are America’s witnesses to the Holocaust.

Tracking down veterans who were at the camps would have been much more difficult without the assistance of a key group of veterans (and a few nonveterans), some of whom have done their own research and writing about the liberators. Special thanks go to David L. Israel, the author of

The Day the Thunderbird Cried

, Dan P. Dougherty, Curtis Whiteway, Melvin H. Rappaport, Robert Enkelmann, Dee Eberhart, Forrest Lothrop, Russel Weiskircher, Jim Bird, George Slaybaugh, Jan Elvin, Donna Bernhardt, Mark Miller, Glen E. Lytle, and Robert Humphrey.

Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.) Hugh Foster generously provided me a place to stay while I attended the reunion of the 80th Infantry Division at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, shared his expertise on the liberation of Dachau and on World War II military history, weapons, and tactics, personally guided me in researching World War II records at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and carefully reviewed the manuscript.

I wish to express my gratitude to Walter H. Chapman for generously granting me permission to publish his wartime drawings of Salzwedel, and to his wife, Jean, for her logistical assistance. Thanks, also, to Dee R. Eberhart for permission to use his poem “KZ Dachau,” and to Warren E. Priest for permission to use his poem “My First Encounter.”

Of invaluable assistance in finding documents, photographs, liberators, survivors, and/or essential facts and details were: Geoffrey Megargee, PhD, applied research scholar at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.; Frank R. Shirer, chief, Historical Resources Branch, U.S. Army Center of Military History at Fort McNair, D.C.; Lillian Gerstner of the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center, in Skokie; Dan Raymond, University of Illinois Library archive assistant in Urbana; Judy Janec, archivist at the Holocaust Center of Northern California, in San Francisco; Eleanora Golobic of American Field Service; Donna and Carl Phinney, Jr.; Gloria Deutsch of

The Jerusalem Post;

Baker Mitchell; and Theresa Lynn Ast, PhD, associate professor of history at Reinhardt College, whose encouragement and doctoral dissertation, “Confronting the Holocaust: American Soldiers Who Liberated the Concentration Camps,” provided a starting point for my research.

As she’s done for my previous books, Kathy Kirkland typed the interview transcripts, did an exceptional job of online research following leads generated by those interviews, and did her best to ensure that essential material was not overlooked.

Thanks to my information tech guru, Manuel Leyeza, who also served as my principal translator of German documents, and to my mother, Essie Hirsh, who was my go-to expert for Yiddish translations.

A select group of friends and relatives provided support, advice, and encouragement during the research and writing process, read early drafts, offered constructive criticism, and helped in other meaningful ways. They are Jon Eisenberg, Ira Furman, Todd Katz, Richard Greenwald, Peter Herford, Mike Farrell, Saryl Radwin, Leslie Sewell, Jennifer and Joel Weisberger, Rose and Robert Aronson, Richard and Laura Aronson, Sam Sola, and Jay Wolfson.

My agent, Matthew Bialer of Sanford J. Greenburger, Associates, was especially supportive of this project from the beginning, and was instrumental in shaping the proposal that ultimately resulted in this book. Thanks also to his assistant, Lindsay Ribar.

My editor, Philip Rappaport, and Bantam Dell’s publisher, Nita Taublib, expressed immediate enthusiasm for this project, and expended extraordinary effort to make it successful. I also want to thank the book’s designers, Casey Hampton and Barbara Bachman; the cover designer, Robbin Schiff; and the publicity department at Bantam Dell, especially its director, Theresa Zoro, and publicists Katie Rudkin and Diana Franco. Thanks also go to my editor’s assistant, Angela Polidoro; the copy editor, Lynn Anderson; the proofreaders, Maralee Youngs and Tita Gillespie; the cartographers, Mapping Specialists, Ltd.; and the production editor, Steve Messina.

Living with someone who has chosen to bury himself in the ugliness of the Holocaust for an intense, albeit limited, length of time, has its downside. And that is why I conclude these acknowledgments with particular thanks and love to the woman who, for more than forty years, has made me a better person, my wife, Karen.