The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust (36 page)

Read The Liberators: America's Witnesses to the Holocaust Online

Authors: Michael Hirsh

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Holocaust, #Psychology, #Psychopathology, #Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Nurse Charlotte Chaney married her late husband, Bernie, in 1944. A few months later she went to Europe with the 127th Evacuation Hospital, which eventually was assigned to care for survivors of Dachau. In one of her letters home she wrote, “Our job was to separate the living, the half-living and the dead.”

The prisoners who were outside the barracks were apparently those in the best physical condition. It’s when she went into the buildings that she was confronted with the ultimate in horror on bunks stacked three high. “We’d walk into a barrack, and there you saw what it was. They were like skeletons, so close together. We started to go in and clean out. We took them over to where the German GIs stayed, it was on the other side of the camp, and the Army came in with beds and linens, and we would delouse them. We had sprays, we shaved them, put on clean clothes. We had to do it for some of them. We set up like a triage, and then we realized we were going to need help, lots of help, because there were so many people there.”

When the Americans first came to Dachau, they reported that as many as three hundred or four hundred inmates died each day. Chaney remembers fifty to one hundred dying daily, for several days. Their job was to separate the living from the half-living from the dead. “We couldn’t stop to even think, because there’s so many hundreds and hundreds of people. There were children there that we tried to get to. And then to feed these people, we couldn’t give them regular food right away, we had to start off with a gruel because their digestive systems were shot, you know? And even if we gave them a crust of bread, they would hide it under their pillow. We’d try to tell them, ‘You’ll get more, you don’t have to do that anymore.’ But …” her voice trails off, her eyes misting, the scene playing over in her mind.

The fact that she spoke Yiddish helped somewhat in communicating with her patients, many of whom were suffering from typhus and TB. To try to avoid succumbing to the diseases they were treating, the doctors and nurses wore long gowns and masks, had their heads wrapped, and wore rubber gloves. And they were regularly sprayed with DDT powder.

The odor is still with her. “It was a distinctive smell or odor that you got—you know, if you walk into a room with a lot of people that are ill, they have a distinctive odor. This was ten times worse.”

Their priority was to get the inmates out of the barracks and into the rapidly expanding hospital as quickly as possible. “We would just get ‘em out of there, get ‘em cleaned up, put them in clean beds, and start giving them food, gradually increasing the diet. Those that couldn’t even eat gruel were given IV feedings. And that was all that we could do at the time. We worked practically day and night.” She says the nurses were overwhelmed, “always, every day. There were so many, and the children. These kids with the bloated bellies from starvation.”

She saw the bones and the bodies behind the crematorium that the Germans had not had time to bury and was there when they brought civilians from Munich to dig graves. They were asked, “Didn’t you see anything? Didn’t you smell anything? Didn’t you see the smoke? Nothing.”

And then they went to see the boxcars, the death train.

Sitting in her Hollywood, Florida, apartment sixty-four years later, holding the boxes of letters she wrote home from the war, she knows that she’ll never forget her experiences at Dachau, and she doesn’t want others, especially today’s children, to forget either. “It’s always in the back of my head, even when I go out and speak to schools, to the children, I try to make them understand what happened, and to this day, we still don’t know—because for people to follow a crazy man, you know, he should have been put away.”

And God? She questions where God was. “If there was a God above, why did this happen? To let this happen—my belief in God went way down. Even to this day, I still can’t understand. They say there is somebody up there looking after everybody. I say, how? In the Holocaust, there was nobody, nobody.”

Shortly after the 127th Evac had set up operations at Dachau itself, arrangements were being made to transport some inmates in dire need of medical care to the 120th Evac, which had moved from Buchenwald to Cham, a town about a hundred miles northeast of Dachau. Within days the 120th was treating more than nine hundred former prisoners hospitalized in five different buildings.

Len Herzmark, who was a medic, not a doctor, has one very precise memory of his time with the unit at Cham. “I had a patient whose hands were paralyzed for whatever reason, and while we were working the inspector came through from Army headquarters somewhere, a medical inspector, just wanted to look at what we were doing—you know, visited with some of the patients and so on. And after he left, this one patient who had the paralyzed hands, he said, ‘Did the doctor give you any recommendation for my paralysis?’ And I knew that this guy wasn’t really paralyzed, you could tell, you know? So I said ‘Yes,’ and I’d probably be shot for this today, but I got a syringe of saline, sterile saline solution, and I gave him an injection, a muscular injection in the back between the shoulder and elbow, the muscle there. And you know, the next day, he was folding blankets. I cured him.”

Two days after the liberation of Dachau, the 45th Infantry Division’s Leonard “Pinky” Popuch, who after the war became Leonard S. Parker, an acclaimed architect who designed the Minneapolis Convention Center, the State of Minnesota Supreme Court Building, and the U.S. Embassy in Santiago, Chile, wrote a nine-page letter to his family at home in Milwaukee. In a bold hand, he assured them of his safety and assessed his life and the world around him. “I am still well and trusting in God. A little tired and worn out perhaps, and maybe a little older, now, than my 22 years—but well, never-the-less.”

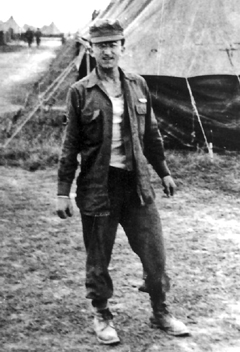

Leonard “Pinky” Popuch, later Leonard Parker, sang Yiddish songs to the Jewish Dachau inmates, who had a difficult time believing there were Jewish soldiers in the U.S. Army

.

He’d last written when his company was at Nuremberg. Now he wrote, “Many times since I have come overseas, while miserable in a wet foxhole, or sweating out a Jerry artillery barrage, or lying out in the rain pinned down by enemy small arms fire, I have asked myself what it is all about. Why am I here—why! why! why!”

Dachau answered his questions, and he tried to help his family understand. He described the death train and the bodies and said, “We took no German prisoners that day … they are no better than swine and we treated them as such. We saw and smelled the crematorium where they cremated the dead bodies after removing the shoes and any other valuables the people might possess … we heard from the lips of the prisoners themselves as to how they were beaten and starved and made to work anywhere from 12 to 18 hours in one day. We listened to countless stories of cruelty and the inhumanity of the Nazis and it made one want to tear the eyes out of the next German soldier you saw.”

He went on to describe the first prisoner he heard speak—of all things, a U.S. Army captain who had parachuted into France before D-Day and been captured by the Gestapo and sent to Dachau. And he wrote about the prisoners who kissed the Americans, crying for joy:

They fell on the ground at our feet and kissed our boots and grabbed our hands and kissed them, and these suffering, crying Jewish people yelled,

“Dank gott was ze haben gekumen—yetzt zenen mir frie”

[Thank God you came—now we are free].” There were women, children and men alike—those that were able to walk—all crying, half mad with happiness.

A Jewish man came up to me and asked me if it were true that there were Jewish soldiers in the American army. When I told him that I was a Jewish “unteroffizier” he nearly went mad. Soon I had about 50 Jewish men and women around me hugging and kissing me. They were starved also for “das Yiddishe giest” [Jewish spirit], and I wanted so much to make them happy. I sang some “chazonish shticklach” [Jewish cantorial music] for them, and all, “A Yiddishe Mama.”

I saw firsthand the things that I have heard about and which I had never quite believed. Now, I know what this war is all about. Now I know why we are fighting. To me, all the suffering and misery I’ve had to put up with these past 8 months has been well worthwhile. Just to see the joy on the faces of these tortured, suffering people repaid all of us that saw, a thousand fold…. I’m proud to be one of the many who finally helped free those poor souls who have been through a hell that the decent mind cannot imagine possible here on God’s own earth….

… I wanted to let you know of how our people have suffered and that we’re (I mean the Americans) are bringing light in their hearts and maybe in the homes they may have again some day. I have hopes that you’ll feel as I feel, that the anxiety and worry and heart suffering you are going thru is for something. To stamp out the poison Hitler and his kind have spread over the world.

I will write again when I can. I love you all and miss you very much.

Still your same devoted Sammy.

CHAPTER 14

THEY’RE KILLING JEWS-WHO CARES?

THEY’RE KILLING JEWS-WHO CARES?

MAY 2, 1945

AMPFING, GERMANY

52 miles east of Dachau

35 miles southeast of Moosburg

C

oenraad Rood lay in the hole in the ground the Germans had assigned to him and roughly a dozen others when he had arrived at the Waldlager V concentration camp five days earlier. There were only two facts the twenty-eight-year-old Dutch Jew thought relevant at that moment: the Americans were coming, and he would not live to see them.

Just three days earlier, those Americans—the tankers and infantrymen of the U.S. Army’s 14th Armored Division—had liberated Stalag VII-A, the POW camp at Moosburg near the Isar River, freeing an astounding 110,000 Allied prisoners of war.

Nathan Melman was part of a mechanized cavalry reconnaissance platoon attached to the 48th Tank Battalion when Moosburg was liberated, and the twenty-three-year-old enlistee from Trenton, New Jersey, was one of the first Americans into Waldlager V—it means Forest Camp 5—at Ampfing. The 48th didn’t even know the place existed until they stumbled across strange-looking people in striped uniforms. Melman was driving a jeep convoying with a couple of tanks and armored cars traveling down a dirt road through the woods when they happened upon the camp.

He recalls some shooting, but mostly, he says, the Germans “were trying to get the hell outta there, and the prisoners, as weak as they were, they got hold of”—he pauses briefly, then continues, “I think there were five Germans they captured that were guards, and two of them must’ve been so mean and rotten that as weak as the prisoners were, they beat them to death with their bare hands.” This happened after the Americans arrived. “And the other three, they told us they were half decent, not to hurt them, so we let those three go. They just left the bodies of these two lying near the front gate, and when the officers told them, ‘We let you kill them, we didn’t stop you. Now pick them up and take them some place and bury them, we don’t want them laying there.’ Bury them? They all lined up, the ones that were able to walk, and they urinated on them.”