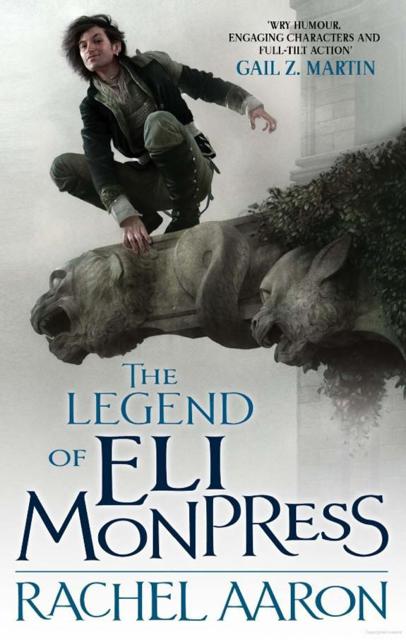

The Legend Of Eli Monpress

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-748-13058-0

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by Rachel Aaron

The Spirit Thief

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Orbit

Copyright © 2010 by Rachel Aaron

The Spirit Rebellion

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Orbit

Copyright © 2010 by Rachel Aaron

The Spirit Eater

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Orbit

Copyright © 2010 by Rachel Aaron

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

For Travis. All the really good ideas are his.

1

I

n the prison under the castle Allaze, in the dark, moldy cells where the greatest criminals in Mellinor spent the remainder of their lives counting rocks to stave off madness, Eli Monpress was trying to wake up a door.

It was a heavy oak door with an iron frame, created centuries ago by an overzealous carpenter to have, perhaps, more corners than it should. The edges were carefully fitted to lie flush against the stained, stone walls, and the heavy boards were nailed together so tightly that not even the flickering torch light could wedge between them. In all, the effect was so overdone, the construction so inhumanly strong, that the whole black affair had transcended simple confinement and become a monument to the absolute hopelessness of the prisoner’s situation. Eli decided to focus on the wood; the iron would have taken forever.

He ran his hands over it, long fingers gently tapping in a way living trees find desperately annoying, but dead

wood finds soothing, like a scratch behind the ears. At last, the boards gave a little shudder and said, in a dusty, splintery voice, “What do you want?”

“My dear friend,” Eli said, never letting up on his tapping, “the real question here is, what do

you

want?”

“Pardon?” the door rattled, thoroughly confused. It wasn’t used to having questions asked of it.

“Well, doesn’t it strike you as unfair?” Eli said. “From your grain, anyone can see you were once a great tree. Yet, here you are, locked up through no fault of your own, shut off from the sun by cruel stones with no concern at all for your comfort or continued health.”

The door rattled again, knocking the dust from its hinges. Something about the man’s voice was off. It was too clear for a normal human’s, and the certainty in his words stirred up strange memories that made the door decidedly uncomfortable.

“Wait,” it grumbled suspiciously. “You’re not a wizard, are you?”

“Me?” Eli clutched his chest. “I, one of those confidence tricksters, manipulators of spirits? Why, the very thought offends me! I am but a wanderer, moving from place to place, listening to the spirits’ sorrows and doing what little I can to make them more comfortable.” He resumed the pleasant tapping, and the door relaxed against his fingers.

“Well”—it leaned forward a fraction, lowering its creak conspiratorially—“if that’s the case, then I don’t mind telling you the nails do poke a bit.” It rattled, and the nails stood out for a second before returning to their position flush against the wood. The door sighed. “I don’t mind the dark so much, or the damp. It’s just that people

are always slamming me, and that just drives the sharp ends deeper. It hurts something awful, but no one seems to care.”

“Let me have a look,” Eli said, his voice soft with concern. He made a great show of poring over the door and running his fingers along the joints. The door waited impatiently, creaking every time Eli’s hands brushed over a spot where the nails rubbed. Finally, when he had finished his inspection, Eli leaned back and tucked his fist under his chin, obviously deep in thought. When he didn’t say anything for a few minutes, the door began to grow impatient, which is a very uncomfortable feeling for a door.

“Well?” it croaked.

“I’ve found the answer,” Eli said, crouching down on the doorstep. “Those nails, which give you so much trouble, are there to pin you to the iron frame. However”—Eli held up one finger in a sage gesture—“they don’t stay in of their own accord. They’re not glued in; there’s no hook. In fact, they seem to be held in place only by the pressure of the wood around them. So”—he arched an eyebrow—“the reason they stay in at all, the only reason, is because you’re holding on to them.”

“Of course!” the door rumbled. “How else would I stay upright?”

“Who said you had to stay upright?” Eli said, throwing out his arms in a grand gesture. “You’re your own spirit, aren’t you? If those nails hurt you, why, there’s no law that you have to put up with it. If you stay in this situation, you’re making yourself a victim.”

“But …” The door shuddered uncertainly.

“The first step is admitting you have a problem.” Eli

gave the wood a reassuring pat. “And that’s enough for now. However”—his voice dropped to a whisper—“if you’re ever going to live your life,

really

live it, then you need to let go of the roles others have forced on you. You need to let go of those nails.”

“But, I don’t know …” The door shifted back and forth.

“Indecision is the bane of all hardwoods.” Eli shook his head. “Come on, it doesn’t have to be forever. Just give it a try.”

The door clanged softly against its frame, gathering its resolve as Eli made encouraging gestures. Then, with a loud bang, the nails popped like corks, and the boards clattered to the ground with a long, relieved sigh.

Eli stepped over the planks and through the now-empty iron doorframe. The narrow hall outside was dark and empty. Eli looked one way, then the other, and shook his head.

“First rule of dungeons,” he said with a wry grin, “don’t pin all your hopes on a gullible door.”

With that, he stepped over the sprawled boards, now mumbling happily in peaceful, nail-free slumber, and jogged off down the hall toward the rendezvous point.

In the sun-drenched rose garden of the castle Allaze, King Henrith of Mellinor was spending money he hadn’t received yet.

“Twenty thousand gold standards!” He shook his teacup at his Master of the Exchequer. “What does that come out to in mellinos?”

The exchequer, who had answered this question five times already, responded immediately. “Thirty-one thousand

five hundred at the current rate, my lord, or approximately half Mellinor’s yearly tax income.”

“Not bad for a windfall, eh?” The king punched him in the shoulder good-naturedly. “And the Council of Thrones is actually going to pay all that for one thief? What did the bastard do?”

The Master of the Exchequer smiled tightly and rubbed his shoulder. “Eli Monpress”—he picked up the wanted poster that was lying on the table, where the roughly sketched face of a handsome man with dark, shaggy hair grinned boyishly up at them—“bounty, paid dead or alive, twenty thousand Council Gold Standard Weights. Wanted on a hundred and fifty-seven counts of grand larceny against a noble person, three counts of fraud, one charge of counterfeiting, and treason against the Rector Spiritualis.” He squinted at the small print along the bottom of the page. “There’s a separate bounty of five thousand gold standards from the Spiritualists for that last count, which has to be claimed independently.”

“Figures.” The king slurped his tea. “The Council can’t even ink a wanted poster without the wizards butting their noses in. But”—he grinned broadly—“money’s money, eh? Someone get the Master Builder up here. It looks like we’ll have that new arena after all.”

The order, however, was never given, for at that moment, the Master Jailer came running through the garden gate, his plumed helmet gripped between his white-knuckled hands.

“Your Majesty.” He bowed.

“Ah, Master Jailer.” The king nodded. “How is our money bag liking his cell?”

The jailer’s face, already pale from a job that required

him to spend his daylight hours deep underground, turned ghostly. “Well, you see, sir, the prisoner, that is to say”—he looked around for help, but the other officials were already backing away—“he’s not in his cell.”