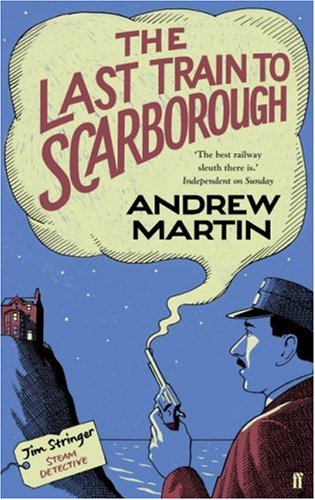

The Last Train to Scarborough

Read The Last Train to Scarborough Online

Authors: Andrew Martin

The Last Train

to Scarborough

Andrew Martin

First published in 2009

by Faber and Faber Limited

3 Queen Square London WCIN 3AU

Typeset by Faber and Faber

Limited

Printed in England by CPI

Mackays, Chatham

All rights reserved

© Andrew Martin, 2009

The right of Andrew Martin to be

identified as author of this work

has been asserted in accordance

with Section 77 of the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP record for this book

is available from the British

Library

ISBN 978-0-571-22969-7

For all the

people in the Quiet Carriage

I would like to thank, in no

particular order: Roy Lambeth of the Durham Mining Museum; the World Ship Society

and especially Mr Roy Fenton; Drene Brennan of the Postcard Club of Great

Britain; Dr E. M. Bridges of the Museum of Gas and Local History at Fakenham,

Norfolk; Tony Harden of the Railway Postcard Collectors' Circle; Andrew Choong,

Curator of Historic Photographs and Ships Plans at the National Maritime

Museum; Mr N. E. C. Molyneux of the National Rifle Association; Adrian Scales

of the Scarborough Railway Society; Sue Pravezer, QC; Clive Groome of Footplate

Days and Ways; Rod Lytton, Chief Mechanical Engineer at the National Railway

Museum and' Karen Baker, librarian at the Museum.

All departures from historical

fact are my responsibility.

Table of Contents

One

As

I awoke the thought came to me:'

Where has Scarborough got to?'

and it caused me a good deal of pain. I knew I was near coal - too near. I was

on

it. Or was it a great black beach, for I heard waves too?

There was darkness above as well as below, but not quite complete darkness

above, for I could make out thin strips of light. Each thought caused me a

blinding pain behind the eyes and I did not want any more to come.

I

inched a little way to the left, and the coal smell was stronger. It disagreed

with me powerfully, and I saw in my mind things to do with coal and burning as

the nausea came on: a locomotive moving coal wagons in an empty station that

ought to have been packed with holiday-makers; a man making coal-gas tar at

the works on the Marine Parade at Scarborough, and evidently doing it for his

own amusement, for he was the only man in the town. A storm approached across

the black sea behind him.

I

saw the booklet that gave directions for use of an incandescent oil lamp - it

gave sunshine at night through a red shade, one hundred and twenty candles -

and I saw smoke over Scarborough, and further general scenes of that sea-side

town in the hour before the lamps are lit: the funicular railway closed and not

working; the locked gate at the entrance to the underground aquarium and

holiday palace. I figured an orchestra locked inside there along with a troupe

of tumblers, and a magician who was the wonder of the age but nevertheless

troubled by a leaking kettle.

I

saw the harbour of the town with the boats at all angles, as though they'd been

dropped

in only moments before, and were still struggling to

right themselves.

I

saw a public house with a ship's figurehead on the front, a marine stores, the

sign reading 'All Kinds of Nets Sold' lashed by waves ... and nobody about. I

pictured the great hotel - I could not recall its name and knew it would cost

me pain to try and do so. I saw the high, windowless wall to the side, streaked

with rain - the place was a prison viewed from that angle. I heard a great

roaring of water on the other side of that wall. Flags flew from what might

have been flagpoles at the top or might have been masts, and in my mind's eye

the monstrous building slid away from the Promenade, and began bucking about on

the dark sea.

These

scenes were mainly without colour, but then some colour came, and it was wrong,

too bright, done by hand: a red baby in a sky-blue cot set in a yellow room.

That baby was on a post card - that was

its

trouble, and

at the thought my stomach lurched fruitlessly while the head-racking pain

redoubled. I moved on the coal and the same convulsion came again, only worse.

My stomach was trying to do something it could not do. I thought of a short

cigar taken from a cedar-wood box. It was a little dry. But what was dry? Box

or cigar? At any rate the room containing the cigar was too hot, yet how could

it be, for it was part of heaven? No, not quite heaven. A voice echoed in my

head: 'It's turned you a bit bloody mysterious, this Paradise place.' Paradise.

Somehow, a secret file was involved, a pasteboard folder containing papers

that everybody looked at, and yet it was secret. I saw a jumble of razor

blades, a fast-turning dial on what might have been a compass, but surely ought

not to have been. My mind could hold ideas and pictures but could not make the

connections between them.

I

looked up again at the light strips. I raised my arm towards them, and they

were a good way above the height of my hand. My arm wavered and fell; it was

not long enough, and that was all about it. I was perhaps underneath the

floorboards, in some species of giant coal cellar, and this notion came with a

new sensation: a fearful sense of eternal falling. Some of my memories were

coming back to me, and coming too fast. I closed my eyes on the great coal

plain and raced down, down, down.

Two

And

there in place of Scarborough was the city of York, or the outskirts thereof:

our new house, 'the very last one in Thorpe- on-Ouse', as our little girl,

Sylvia, used to say, the house that put off the beginning of open country. It

was evening - early evening, spring coming on; a kind of green glow in the sky,

and I sat in my shirt sleeves and waistcoat. They had been ploughing in the

fields around the village, but I'd not seen the work carried on, for I'd passed

all day in the police office in York station.

I

sat on the front gate with Sylvia, and our boy Harry. They both liked to sit up

high - well, it was high to them, Sylvia especially, and I had my arm around

her to stop her falling, which she didn't like. Not the falling I mean, but the

arm. She wanted to sit on the gate unsupported like Harry, who now pointed

along the lane, saying, 'Here he comes', and old Phil Shannon, who lit the

lamps in Thorpe-on-Ouse and at Acaster Malbis, was approaching on his push

bike, with the long lamplighter's pole held at his side. I fancied that it was

a lance, and Shannon a sort of arthritic knight on horseback. He leant

alternatively left and right as he pedalled, like a moving mechanism, some

species of clockwork.