The Last Princess (20 page)

Authors: Matthew Dennison

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty

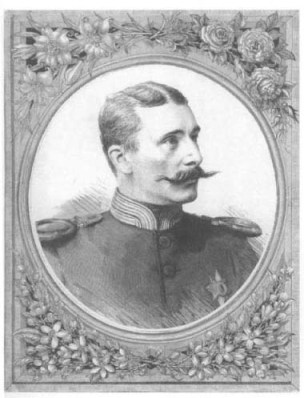

Being in love suited Beatrice—as this striking photograph of 1886 shows.

Public reaction to Beatrice's engagement to Prince Henry of Battenberg was muted – but Beatrice's happiness was hard won and she married for love. These full-page engravings of the couple were published in

The Graphic

on January 10 1885.

With her ‘quite simple’ dress, Beatrice wore the Queen's own wedding veil of Honiton lace. Henry, known as ‘Liko’, wore the white uniform of the Prussian Garde du Corps. The couple were attended by ten bridesmaids (including the future Tsarina of Russia and future queens of Norway and Roumania), all Beatrice's nieces—categorized by one MP as showing a ‘decided absence of beauty’.

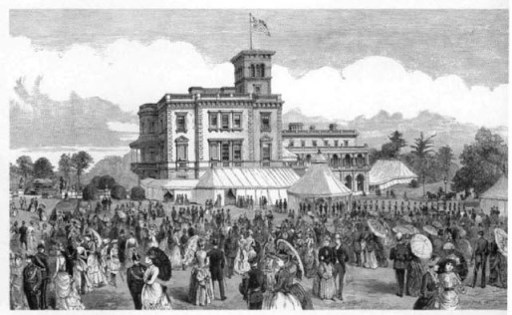

‘The scene at Osborne after the ceremony,’ reported The

Illustrated London News,

‘was that of a jubilant garden party’

Even when visiting what ought to have been gentler climates, the Queen embraced vagaries in the weather. Reporting on her five-week stay in the Provencal town of Grasse in 1891, the French weekly newspaper

Le Commerce

recorded: ‘Despite a chilly and rather disagreeable North wind, Her Majesty Queen Victoria goes out for long drives every morning in her little donkey-chair along the approaches to the Grand Hotel and in the immediate vicinity of the town.’

9

It was nothing, of course, compared with Balmoral, or Osborne at Christmas, and happily there was no room in the donkey-chair for Beatrice, though she would regularly be expected to walk alongside it, keeping her mother company on these sedate all-weather excursions.

The Queen's second daughter Alice had been married to Louis of Hesse for ten years when, on 6 July 1872, Sir James Clark wrote to her about her health. The princess, who would die at

the age of thirty-five, had complained for some time about her poor physical condition. During the Austro-Prussian war of 1866, her letters to her husband described her worsening rheumatism and neuralgia, tiredness, strain and headaches.

10

Helpfully, Clark's letter prescribed well-ventilated rooms and ‘steady perseverance in the use of the cold bath every morning’.

11

If the doctor appears to have been blind to the workings of cause and effect, it was a failing the Queen shared. She was neither unaware of nor unsympathetic to the sufferings Beatrice's rheumatism imposed, although she regarded its earliest manifestations as an inconvenience to herself rather than Beatrice—as, for example, when it threatened to cast a blight over the royal excursion to Loch Maree in September 1877: ‘Dear Beatrice suffered much from rheumatism, which was very vexatious.’

12

Beatrice herself took care that her infirmity did not become a preoccupation, forewarned by the example of her haemophiliac brother Leopold, who was regularly confined to his bed by mishaps arising from his condition or, more frustratingly, by the Queen's determination to prevent such mishaps. Unlike her sister Helena, Beatrice did not mollycoddle herself. Unlike the Queen, she was not prone to hypochondria. In January 1878, despite suffering from a cold that ultimately prevented her presence at dinner, Beatrice rode out in the morning with Mademoiselle Norele. The following New Year, Lady Waterpark's diary noted, ‘A wretched day, snow and wind. Miss Phipps went to skate with Princess Beatrice.’

13

Despite suffering from the cold and her preference for warm weather, Beatrice did not, as a young woman, allow this to curtail her activities. Partly, her pragmatic attitude arose in response to circumstances: her daily attendance on the Queen necessitated long periods outdoors regardless of the weather. Towards the end of her life the Queen suffered as much as her daughter from rheumatic pains and cramps, she had difficulty walking and her legs troubled her. But she continued to relish the cold. At Balmoral in November 1896 Marie Mallet confided to her diary, ‘The Queen quite apologized yesterday for enjoying the cold weather so intensely. “I always feel so brisk,” said she!

It is more than her daughters or Ladies do!’

14

As a child, Beatrice had joined her mother for tea at Frogmore on a day of such driving wind that even the doughty Queen was forced to sit under the Colonnade. As an adult, Beatrice was better able to resist her mother's whims, where resistance was compatible with the satisfaction of both. ‘The Queen insisted on sitting out last night on the Terrace,’ wrote Marie Mallet of an evening at Osborne in July 1898, ‘but mercifully the Princesses refused to run the risk of rheumatism and kept me with them.’

15

A stout heart and sense of duty were not enough to ease Beatrice's pain. In the summer of 1883, on the pressing advice of the Queen's doctors, she travelled to Aix-les-Bains in the South of France to take a cure. The timing was unfortunate. John Brown had been dead less than six months and the Queen herself was far from fully recovered from her fall at Windsor in the spring. She felt Beatrice's absence keenly, leaving her as it did temporarily bereft of either of her twin supports, without even Leopold to fall back on since his marriage the previous year. Her sympathy was roused for her favourite daughter, but most of the Queen's thoughts focused firmly on her return. To her old friend and occasional sparring partner Augusta of Prussia, since Prussia's defeat of Napoleon III raised to the rank of empress, the Queen wrote:

Beatrice's absence is very grievous and unpleasant and increases my depression and the horrible ever growing feeling of emptiness and bereavement which nothing can ever really remove. But recently she had been suffering a great deal from neuritis, especially in the hand and right arm, which was a great inconvenience to her in writing and especially in playing the piano, and before that she had it in her knee and foot too. So we thought it would be advisable to try a thorough cure for three weeks.

16

Beneath the tetchy self-pity of a woman unaccustomed to inconvenience is a genuine pang of longing for her absent daughter. The Queen was unused to being parted from Beatrice – she wrote to the Crown Princess, ‘Her absence is of course a great trial to me as for twenty-two years she has only been absent for ten days

once.’

17

The Queen missed Beatrice: their separation, albeit brief, brought home to her the extent of her dependence. The union the Queen described to the Crown Princess was, at twenty-two years, of longer duration than her marriage to the Prince Consort. Its temporary suspension was an unpleasant novelty. The Queen required Beatrice for emotional reasons, particularly in the wake of John Brown's death, but the demands of her unrelenting paperwork were equally exigent. Beatrice may have hoped that the thermal cure at Aix-les-Bains would lessen her aches and enable her again easily to play the piano; on the Queen's agenda was the ‘writing’ Beatrice undertook for her – letters, telegrams, and even copying in the case of letters she considered of special importance.

Beatrice's time away was not spent selfishly. At the end of August the Queen wrote to her eldest daughter from Osborne, ‘The heat is intense since Saturday, and tires me very much. I am however getting on and I hope “Charlotte” whom Beatrice swears by will finish the rest.’

18

The Queen's ‘Charlotte’ was Charlotte Nautet, a masseuse from Aix-les-Bains recommended by Beatrice. In future the Queen's doctor James Reid would arrange for Charlotte and her successor Marie Angelier to spend two- and three-week periods staying with the Queen, holding at bay her own rheumatic lameness through massage. For the Queen to claim Beatrice swore by Charlotte indicates that the princess derived some benefit from her cure at Aix-les-Bains, as does the fact that the visit was repeated in 1887, although on that occasion the Queen and Beatrice travelled together.

Her summer cure at Aix-les-Bains was not Beatrice's first experience of the South of France. Her brother Leopold had travelled there repeatedly for his uncertain health and, in 1882, the Queen chose Menton as the destination for her spring holiday. During that holiday Beatrice asked to visit Nice. The gunboat

Cygnet

was placed at her disposal to transport her. A foretaste of her trip to Aix-les-Bains, she made the short journey without her mother. Afterwards, leaving France on board the royal yacht

Victoria and Albert,

Beatrice awoke on the morning of her

twenty-fifth birthday to find herself being serenaded by the band of the 25 th Regiment of the French Army; it dedicated to her Meyer's march ‘Salut a la Princesse’.

Such courtesies, Beatrice understood, were paid to her not for herself but in recognition of her relationship to the Queen. Yet, little by little, they added to her growing sense of self. Since the Queen's lameness in the spring of 1883 she had embarked on a limited programme of public engagements deputizing for her mother. In March she presented prizes to the students of the Bloomsbury Female School of Art, and after her return from Aix-les-Bains and the court's removal to Balmoral, she visited Aberdeen to open a bazaar in aid of the Aberdeen Hospital for Sick Children and, in front of a crowd of several thousand, the Duthie Park, recently donated to the town. The ceremony took place on an early-autumn day of driving rain of a sort familiar to the illustrator of

The Graphic.

Planting a tree in the downpour, Beatrice charmed those around her with a joke that the weather would be good for the tree. Such appearances compounded the effect of her constant presence at the Queen's side and meant that Beatrice, the shyest of the Queen's children, was among the best known. She became a favourite of journals such as the

Illustrated London News,

which devoted many column inches to the Royal Family and, at the time of Beatrice's marriage, would review her recent history through the public's eyes: ‘So much interest has long been felt in Princess Beatrice, the Queen's youngest daughter and the last of her children, after the marriage of all her brothers and sisters, that we believe more popular sympathy was felt upon this occasion than at any other Royal Wedding since that of the Prince and Princess of Wales.’

19