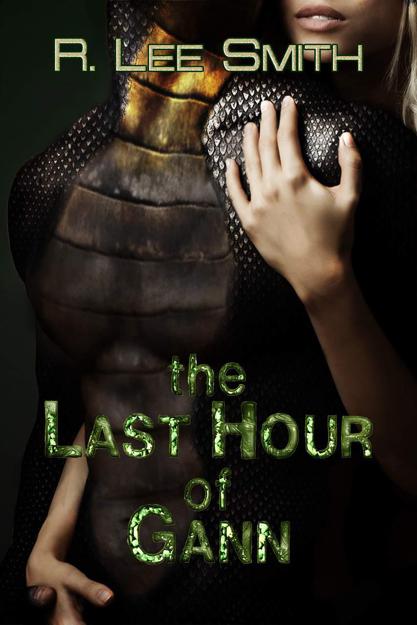

The Last Hour of Gann

THE LAST

HOUR

of

GANN

Copyright © 2013

by R. Lee Smith

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, but not limited to, photocopying or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author.

This book is a work of fiction.

Names, places, locales and events are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, places or events are purely coincidental.

Also by R. LEE SMITH:

Heat

The Lords of Arcadia Series

:

The Care and Feeding of Griffins

The Wizard in the Woods

The Roads of Taryn MacTavish

The Army of Mab

Olivia

The Scholomance

Cottonwood

COMING SOON

Pool

BOOK

I

AMBER

T

he eviction notice was hanging on the door when they got back from the hospital. The time stamp said 1:27 am, six minutes after Mary Shelley Bierce’s official time of death, an hour and twenty-eight minutes before her two daughters sitting in the waiting room had even been informed.

Amber sent Nicci in to bed while she stood out in the hall and read. The eviction gave them thirty days to either vacate or sign under the terms of the new lease, a copy of which was attached. Amber read them. Then she folded up the notice and slipped it into her pocket. She made herself a pot of coffee and sipped at it while watching the news. She thought. She said hello when Nicci woke up and that was all. She went to work.

The funeral was held three days later, a Tuesday. The insurance company covered the cost, which meant it was a group job, and although it was scheduled ‘between the hours of eight and eleven,’ the other funerals apparently dragged long and then there was lunch and so it was nearly two in the afternoon before Mary’s name was called and the cardboard case with her label pasted on the side slid by on the belt and disappeared into the oven. Nicci cried a little. Amber put her arm around her. They got a lot of dirty looks from the other mourners, even though it had only been sixteen years since Measure 34 had passed—Zero Population Growth, Zero Tolerance—and they had both been born by then.

Amber was used to getting dirty looks when she went out with Nicci. Sometimes siblings could pass themselves off as cousins or, even better, as just friends, but not the Bierce girls. Even with different fathers, they were each their mother in miniature and

the three years between them had an oddly plastic quality: in the right light, they could be mistaken for twins; in the wrong light, Amber had occasionally been addressed as Nicci’s mother. Part of that was the size difference—Nicci was, as their mother used to be, fine-boned and willowy below that round, cherubic face, while Amber was pretty much round all over—but not all of it. “You were just born old, little girl,” as her mom used to say. “You were born to take care of things.”

She tried to take it as a compliment. The only part of Mary Bierce that knew how to be a mother had been cut out

years ago and tossed in a baggie with a biohazard stamp on the side. The parts that were left after that didn’t give a damn about homework or lunches or scrubbing out the toilet once in a while. Someone had to be the responsible one and if Amber wasn’t actually born knowing that, she sure learned it in hurry.

* * *

There could have been a lot more than two children at the funeral if it hadn’t been for Measure 34. Mary Bierce (known to her clients as Bo Peep for her curly blonde hair, big blue eyes and child-sweet face, a name she was quick to capitalize on with frilly panties and ribbons and the intermittent plush sheep) had never been the careful sort. Amber had been putting out cigarettes, sweeping up broken bottles, and making sure the door was locked since she was six; she knew damned well that her mom wasn’t going to lose a good tip by insisting her clients wore a condom when she was working. Bo Peep had been to the aborters three times that Amber knew of and there had probably been others, but that all ended with the Zeros and Measure 34. One day, she went off for her regular monthly shots and came staggering home three hours later wearing a diaper. She sort of collapsed onto the sofa, sprawled out like she was drunk, only she wasn’t loud and laughing the way she ought to be. Her mouth had hung open slightly and there was some kind of gooey paste caked at the corners of her lips. All her makeup had been wiped away and none too gently; she looked haggard and sick and dead. Nicci—easily frightened under normal circumstances and utterly terrified by this slack-faced stranger who looked like their mom—started crying, and once she did, Mary Bierce burst out into huge, wet sobs also. She lay spread out over the sofa with her legs wide open and that plastic diaper showing under her skirt while her daughters hugged each other and stared, but all she seemed capable of saying was one nonsensical word.

“Spay

ed!” their mother wept, over and over, until she was screaming it. Screaming and digging at her stomach so hard that one of her bubblegum-pink fingernails broke right off. “Spayed me!

Those motherfuckers spayed me

!”

At last, in a kind of desperation to quiet everybody down before one of the neighbors had them written up again, Amber climbed up on the kitchen counter and brought down a bottle of her mom’s black label. She poured a juice glass for Mary and, after a moment’s uneasy deliberation, a sippy-cup for Nicci and made th

em both drink. Within an hour, they were both asleep, but her mom kept crying even then, in a breathy, wailing way she couldn’t quite wake up for, and all she could say was that word.

Spayed.

Later, of course, she had plenty to say—about Measure 34 and the Zero-Pop zealots who passed it, about the insurance company and their fine print policies, and about men. It always came back to the men.

“They’ll spay the hookers, sure they will,” she’d sneer at some point. “But do they ever talk about neutering the fucking johns? Oh no! No, they’re still selling Viagra on the fucking TV, that’s what they’re doing! Let me tell you something, babies, what I do is the most honest work in the world because all women are whores! That’s how men see it and if that’s how they see it, little girl, that’s how it

is

!”

And Amber would nod, because sometimes if you agreed enough early on, the real shouting never got started, but privately she had her doubts. Privately she thought, even then at the age of eight and especially as she got older and Bo Peep Bierce grew more and more embittered, that it didn’t prove a whole lot to say that men thought all women were whores when the only men you saw in a day were the ones…well, buying a whore. If you want to hang with a better class of man, Amber would think as she nodded along with her mother’s rants, quit whoring.

Not that you could quit these days. But it had still been her choice to start.

And these probably weren’t the most respectful thoughts to be having at your mother’s funeral. Amber gave Nicci’s sh

aking shoulders a few more pats and tried to think of good things, happy memories, but there weren’t many. Her mind got to wandering back toward the eviction and the Manifestors. It had better be today, she decided, listening to Nicci cry.

After the funeral. But today.

* * *

She didn’t say anything until they got back to the apartment. Then Amber sat her baby sister at the kitchen table and put two short stacks of papers in front of her. One was the eviction notice, the new lease, and a copy of their mother’s insurance policy. The other was an inform

ation packet with the words

Manifest Destiny

printed in starry black and white letters on the first page.

“Please,” said Nicci, trying to squirm away. “Not right now, okay?”

“Right now,” said Amber. She sat down on the other side of the table, then had to reach out and catch her sister’s hand to keep her from escaping. It was not a gentle grip, but Amber kept it in spite of Nicci’s wince and teary, reproachful look. Sometimes, the bad stuff needed to be said. That was the one thing Mary Bierce used to say that Amber did believe.

“We’re going to lose this place,” Amber said

bluntly. “No matter what we do—”

“Don’t say that!”

“—we’re going to lose it.”

“I can get another job!” Nicci insisted.

“Yeah, you can. So can I. And they’ll be two more full-time shifts at minimum wage under that fucking salary cap because we dropped out of school. And that means that the most—the absolute most, Nicci—that we can make between us will be not quite half what we’d need for the new rent.”

“What…? N-no…” Nicci fumbled at the papers on the table, staring without comprehension at the neat, lawyerly print on the new lease. “They…They can’t

do that!”

“Yes, they can. They did.

Maybe they couldn’t raise Mama’s rent, but they can sure do it to us.”

“How do they expect us to pay this much every month?”

“They don’t. They expect to evict us. They want to get a better class of person in here,” she added with a trace of wry humor, “and I can’t say I blame them.”

“But…But where are we supposed to go?”

“They don’t care,” said Amber, shrugging. “And they don’t have to care. We do. And we’ve only got about four weeks to figure it out, so you really need to—” She broke it off there and made herself take a few breaths, because

stop whining

wasn’t going to move the situation anywhere but from bad to worse. “We need to think,” she finished, “about what we can do to help ourselves.”

Nicci gave her a wet, blank stare and moved the papers around some more. “I don’t…Where…What do you want to do?”

Amber picked up the brochure and moved it a little closer to her sister’s trembling hands. “I went to see the Manifestors.”

Nicci stared at her. “No,” she said. Not in a tough way, maybe, but not as feebly as she’d been saying things either. “Amber, no!”

“Then we’re going to have to go on the state.” She had a pamphlet for that option, too. She tossed it on the table in front of Nicci with a loud, ugly slap of sound. More a booklet than a pamphlet, really, with none of the pretty fonts and colorful pictures the Manifestors put in their own brochure. “Read it.”

“No!”

“Okay. I’ll just run down the bullet points for you. To begin with, it’ll take six to eight weeks before we’re accepted,

if

we’re accepted, so we’ll still lose this place. However, once we’re homeless, there shouldn’t be any trouble getting a priority stamp on our application to move into a state-run housing dorm, so there’s that.”