The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron (22 page)

Read The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron Online

Authors: Howard Bryant

Henry joined Jacksonville, part of the notorious South Atlantic League, as a second baseman in 1953. Along with Felix Mantilla and Horace Garner, he would integrate the league while winning MVP honors.

A staple of the segregated era: black players living in a boarding house in the Negro section of town. White players on the Braves resided at a resort hotel in Bradenton, Florida, during spring training, while Henry, Charlie White (center), and Bill Bruton (right) lived at the home of Lulu Mae Gibson.

During his early years, no player would have as much of an impact on Henry as Bill Bruton (second from right). Bruton taught a young Henry Aaron how to dress, how to tip, places to avoid on the road, and, most important, how to begin pressing Braves management to end the segregationist practices during spring training. From left: Jim Pendleton, Charlie White, Bruton, and Henry Aaron.

Few teams in history ever boasted as powerful a trio in the middle of the batting order as did the Milwaukee Braves, with Henry hitting fourth, between Eddie Mathews (center) and Joe Adcock. Henry loved Mathews, but he and Joe Adcock were never close. Henry believed Adcock to be the most racist member of the Braves. It was Adcock who was responsible for the saddling Henry with the unflattering nicknames “Stepin Fetchit,” “Snowshoes,” and “Slow Motion Henry.”

While baseball focused on his rivalry with Willie Mays, it was Jackie Robinson after whom Henry patterned his career, and Robinson who inspired Aaron to be a person of import following his retirement. Aaron always remembered that Robinson was never offered a job by Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley (right) when he left the game, and he resolved to cultivate relationships with the game’s power brokers.

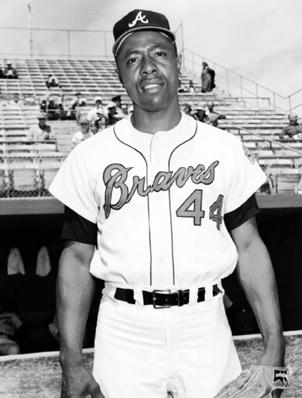

Fresh off of winning his first batting title, Henry arrived in Bradenton for spring training in 1957. By season’s end, he would hit a pennant-winning home run, win the World Series, and secure the Most Valuable Player award for the only time in his career.

On Henry’s first trip to Boston, in May 1957, he and Ted Williams posed before a charity exhibition game at Fenway Park between the Braves and the Red Sox. It was Williams, the curmudgeonly perfectionist, who was both taken by Henry’s accomplishments and perplexed by his unorthodox hitting style. “You can’t hit for power off your front foot,” Williams often said. “You just can’t do it.”

The Wrist Hitter: Perhaps no player in the history of the game would be as celebrated for his lightning-quick wrists as Henry Aaron. “You might get him out once,” Don Drysdale once said, “but don’t think for a minute you’re going make a living throwing the ball past by Henry Aaron.”

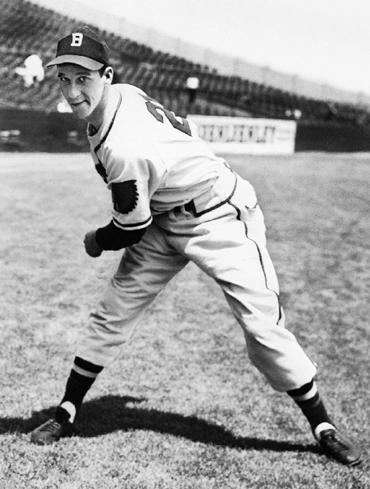

Warren Spahn won 363 games and was the unquestioned leader of the Braves pitching staff. Spahn was a decorated World War II veteran, awarded the Purple Heart and Bronze Star. Along with Henry and Eddie Mathews, Spahn would be elected to the Hall of Fame, but while Henry and Spahn shared mutual respect, Spahn’s irreverence and unprogressive racial attitudes made for a professional but sometimes uneasy relationship.

Henry at home with Barbara, a young Gaile, and infant Lary. The Aarons lived on North 29th Street, in the segregated Bronzeville section of Milwaukee. As Henry’s celebrity increased, the family became the first and only black family allowed to move to the suburb of Mequon, a source of pride and tension on both sides of the roiling civil rights movement in the city.

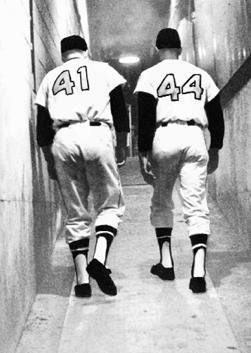

No set of teammates hit more home runs than Eddie Mathews (left) and Henry Aaron, or better symbolized the glory days of baseball in Milwaukee. After the 1965 home finale, the two walk up the runway at County Stadium for the final time before the club moved to Atlanta.