The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA (29 page)

Read The Last Days of Richard III and the Fate of His DNA Online

Authors: John Ashdown-Hill

Appendix 5

DNA evidence relating to the putative remains of Margaret of York preserved in Mechelen, Belgium

The Mechelen Bones

During the twentieth century three sets of female remains were found in the former Franciscan church of Mechelen in locations which could potentially be interpreted as being consistent with the approximate site of the lost tomb of Richard III's sister, Margaret of York.

1

- remains found in 1936 (excavations led by Vaast Steurs)

2 - remains found in 1937 (excavations associated with the name of Maximilien Winders)

3 - remains found in 1955 (accidental discovery, subsequently examined by Professor François Twiesselmann).

4

The bones from the 1955 discovery were photographed at the time, and these bones were subsequently coated with varnish. As a result, they can still be relatively easily identified. It is not now possible to distinguish for certain which of the other female remains from Mechelen's Franciscan priory site were discovered in 1936, and which in 1937.

5

The Samples

On 27 April 2005, in the presence of M. Henri Installé (then archivist of the town of Mechelen), Professor Cassiman of the Catholic University of Leuven took samples of the female remains from the former Franciscan church of Mechelen as follows:

V812/1 Â Â right radius, left ulna and right humerus

V812/2 Â Â left humerus, right ulna, fibula and left femur

V812/3 Â Â a piece of left side lower jaw, right humerus, left femur and a metatarsus

The numbering of the samples corresponds to the numbering of the boxes in which the bones were then stored at the Mechelen Town Archives. V812/2 comprises varnished bones from the 1955 (Twiesselmann) discovery.

6

V812/1 and V812/3 are the remains excavated in the 1930s (Steurs; Winders). As has already been noted, it is not currently possible to state categorically which set of remains are the Steurs bones and which set the Winders bones.

Mitochondrial DNA Analysis of the Mechelen Bones

Professor Cassiman subsequently reported to the town of Mechelen that mtDNA analyses had been successfully carried out, yielding sequences, or partial sequences

7

for some, at least, of the samples taken from each of the three sets of remains (for details, see

Appendix 1

).

V812/1 and V812/3 (comprising the two sets of bones discovered in the 1930s) both yielded uncontaminated results. In the case of each of these skeletons, two distinct specimens had produced consistent and mutually confirmatory results which reveal that the mtDNA of V812/1 belongs to haplogroup V, while the mtDNA sequence of V812/3 belongs to haplogroup J.

Sample V812/2.7

8

also yielded âpure' results, but the remaining samples from V812/2 were contaminated.

9

Supporting evidence in favour of the âpure' sequence found in V812/2.7 was found in each of the other samples from V812/2. However, it remains uncertain whether this sequence is really that of V812/2 or whether it derives from the source of the contamination (possibly the varnish with which the bones had been treated â see above). If the mtDNA sequence yielded by sample V812/2.7 is indeed the mtDNA sequence of the person in question, then that individual belonged to haplogroup H, the most widespread group in Europe.

Comparison with the mtDNA sequence for Margaret of York

The DNA results from the Mechelen remains were compared with the mtDNA sequence of Mrs Joy Ibsen, descendant in an all-female line of Margaret of York's elder sister, Anne of York, Duchess of Exeter. The mtDNA sequence of Joy Ibsen was checked by Professor Cassiman, using cheek swabs (G3993-1.1 and G3993-1.2). Joy's mtDNA sequence belonged to haplogroup J.

10

This indicated that she was, in fact, related in the female line of descent to V812/3 (the individual whose bones were discovered at Mechelen in the 1930s by either Steurs or Winders). This is not particularly surprising, since it is known that Cecily Neville's mtDNA derives from her unknown maternal great grandmother, who quite probably came from the region of modern Belgium. However, Professor Cassiman's detailed examination of mutations in the nucleotide bases outside of the control region normally tested in mtDNA analyses revealed that Joy Ibsen's mutations were not identical to those of V812/3. There were four points of difference between the sequence of Joy Ibsen and that of V812/3,

11

suggesting that their relationship could be quite remote.

12

Moreover, since V812/3 exhibited mutations which Joy did not possess, V812/3 can neither be in, nor close to, Joy Ibsen's direct female ancestral line.

Conclusions

On the basis of this mtDNA analysis, neither skeleton V812/1 nor skeleton V812/3 can be the remains of Margaret of York. This outcome appears consistent with the results of carbon-14 dating tests, carried out on the Steurs and Winders bones in 1969â70, which indicated that these bones were too early in date to be those of the duchess.

13

In the case of skeleton V812/2 the DNA result is necessarily less definitive, due to contamination. The mtDNA sequence apparently revealed for this skeleton certainly does not correspond with Joy Ibsen's sequence. However, it remains uncertain whether the mtDNA sequence yielded equivocally by the V812/2 samples is really that of the skeleton itself. The apparent sequence may merely be the result of contamination. At the present time it is, therefore, impossible to state with absolute certainty that skeleton V812/2 cannot belong to Margaret of York.

In some ways, this is unfortunate. V812/2 is the set of Mechelen remains which some previously considered the most likely (of the three sets of bones found to date) to actually be the remains of Margaret of York.

14

The bones and hair of V812/2 seem to come from the reburial of a corpse which had been disturbed and parts of which had been lost. This hypothesis is not inconsistent with the presumed circumstances surrounding the destruction of Margaret of York's original tomb during the religious disturbances of the sixteenth century. It still remains desirable, therefore, to seek to clarify the position in respect of V812/2.

Summary of the Results of the DNA tests

N.B. only points of difference from the Cambridge Reference Sequence are noted here.

V812/1.1

(humerus) and

V812/1.2

(radius) both yielded:

16298 C; 72 C

V812/2. 7

(tibia) yielded

16354 T

;

263 G

;

315.1 C

This was the only clear set of results for V812/2. The other samples all yielded contradictory double readings in one or more positions.

V812/3.1

(tooth 1) and

V812/3.2

(tooth 2), both yielded:

16069 T

;

16126 C

;

16311 C

;

73 G

;

152 C

;

185 A

;

188 G

;

228 A

;

263 G

;

295 T

;

315.1 C

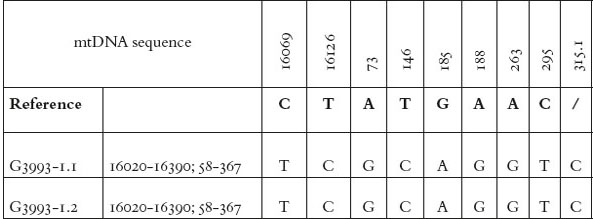

G3993-1.1

and

G3993-1.2

both yielded:

16069 T

;

16126 C

;

73 G

;

146 C

;

185 A

;

188 G

;

263 G

;

295 T

;

315.1 C

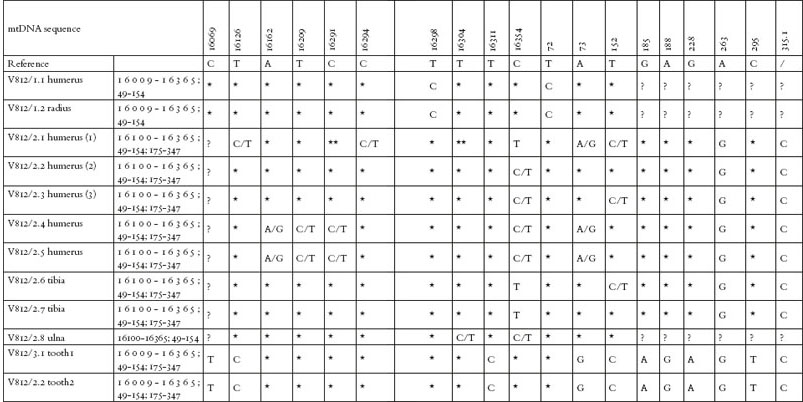

b. The following two tables set out Professor Cassiman's detailed results

T

ABLE

1: The mtDNA sequence of Richard III and his siblings.

The table shows the various positions in the sequence where a difference from an international reference sequence (âAnderson' or âCambridge Reference Sequence') of human mtDNA was observed.

/ = nucleotide not present in the reference sequence

? = sequence could not be determined

* = identical to the reference sequence

** = not possible to obtain confirmation even by the analysis of several DNA fragments G/A (&c) = the presence of two nucleotides

Appendix 6

Richard III's Epitaph

George Buck's Latin Text

George Buck's

History of the Life and Reigne of Richard the Third

is extant in two versions: a posthumous edition published in London in 1647, and reprinted in facsimile with an introduction by A.R. Myers at Wakefield in 1973

1

(hereinafter âBuck 1647'), and an earlier and more accurate text which dates from 1619, but which was not published until the twentieth century, in the edition by Kincaid

2

(hereinafter âBuck 1619'). The following (with one modification â where the text of Buck 1647 appears to give a grammatically more accurate reading)

3

is the epitaph as published in Buck 1619. The punctuation is modern.

4

Variant readings from Buck 1647, and from Sandford are supplied in the footnotes. The greater part of the Latin text of the epitaph is agreed by all the published sources, but there are a number of minor variations, making it somewhat difficult to establish a completely authoritative version.

5

Epitaphium Regis Ricardi

6

tertii, Sepulti apud

7

Leicestriam, iussu et sumptibus Sancti

8

Regis Henrici Septimi

9

Hic ego quem vario tellus sub marmore claudit

Tertius a iusta

10

voce Ricardus

11

eram.

Tutor eram patriae,

12

patruus

13

pro iure nepotis

Dirupta, tenui regna Britanna fide.

Sexaginta dies binis dumtaxat

14

ademptis

Aestatesque

15

tuli tunc

16

mea sceptra duas.

17

Fortiter in bello certans

18

desertus ab Anglis

Rex Henrice tibi septime succubui.

At sumptu pius ipse tuo sic ossa decoras

19

Regem olimque facis regis honore coli

Quattuor

20

exceptis iam tantum quinque

21

bis annis

Acta trecenta

22

quidem lustra salutis erant.

23

Anteque

24

Septembris undena luce Kalendas

25

Reddideram

26

rubrae

27

iura petita

28

rosae.

29

At mea, quisquis eris, propter commissa precare,

30

Sit minor ut precibus poena levata

31

tuis.

Buck's published âtranslation' of Richard III's epitaph

In the early nineteenth century the epitaph was reprinted in John Nichols'

History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester.

His text, complete with notes, appeared also in the additions Nichols made to Hutton's

The Battle of Bosworth Field

, second edition.

32

There, Nichols also supplied the following versified English translation, which he ascribed to Buck.

33

Although the translation is rather free (and indeed, sometimes inaccurate), hitherto this appears to have been the only published English version of the epitaph.

I who am laid beneath this marble stone,

Richard the Third, possessed the British throne.

My Country's guardian in my nephew's claim,

By trust betray'd

34

I to the kingdom came.

Two years and sixty days, save two, I reign'd;

And bravely strove in fight; but, unsustain'd

My English left me in the luckless field,

Where I to Henry's arms was forc'd to yield.

Yet at his cost my corse this tomb obtains,

Who piously interr'd me, and ordains

That regal honours wait a king's remains.

Th'year thirteen hundred âtwas and eighty four

35

The twenty-first of August, when its power

And all its rights I did to the Red Rose restore.

Reader, whoe'er thou art, thy prayers bestow,

T'atone my crimes and ease my pains below.

36