The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (26 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

The mention of ravioli in the caliscioni recipe brings up the second important development that was happening in Sicily at the same time: pasta. Grain-based gruels had long been common in the region, such as the Byzantine Greek gruel called

makaria

( ) eaten as a funeral food (from the Greek

) eaten as a funeral food (from the Greek

makarios

[ ], “blessed”). But dough products closer to true pasta were also an old custom in many parts of the Mediterranean. As far back as the first century

], “blessed”). But dough products closer to true pasta were also an old custom in many parts of the Mediterranean. As far back as the first century

BCE

,

the Greeks ate a dish made from sheets of fried dough called

laganum

, which by the fifth century had become

lagana

, layers of boiled dough alternating with stuffing (says Isidore of Seville)—the ancestor of modern lasagne. But it was

in the eastern Mediterranean that true dried pasta existed

, most commonly eaten in soup or as a sweet dish. We know that the word

itria

was used for both dried and fresh noodles in Aramaic in Palestine in the fifth century (the word appears in

the fifth-century Jerusalem Talmud

), and in the tenth century

itriyah

was an Arabic word for dried noodles

that were bought from a grocer.

It was thus in Sicily

that modern dried durum wheat pasta developed out of these Mediterranean dried noodles. Durum wheat is harder and higher in protein than common wheat, producing firm, elastic dough whose long life makes it easy to store and hence trade great barrels of it by ship. Sicily had been the breadbasket of the Roman Empire because of its durum wheat production, and this hard local wheat was so successfully combined with the Arab noodle traditions that by 1154,

Muhammad al-Idrisi, the Moroccan-born geographer

of Roger II of

Sicily, writes that Sicily was the center of dried pasta production for the whole Mediterranean, sending it by shiploads to Muslim and Christian countries. Different regions used different words for pasta, among them

tria

(from Arabic

itriyah

),

lasagne

, and

vermicelli

(“little worms”). (The idea that Marco Polo introduced pasta to Italy from China is a myth that grew accidentally out of a humorous piece from 1929 in a Minnesota trade publication called the

Macaroni Journal

; by the time Polo returned from China in 1296, pasta had been a major export commodity for almost 150 years.)

By 1200 noodles had branched north from Sicily, carried by both Jews and Christians, and in fact our first evidence for the word

vermicelli

is from France, where

the eleventh-century French scholar Rashi

(or possibly a commentary from one of the medieval Tosafist rabbis that followed him) uses the Yiddish word

vermiseles

, derived via old French

vermeseil

from Italian

vermicelli

, to describe dough that was either boiled or fried.

Vermiseles

soon evolved to

vremzel

and to the

modern Yiddish word

chremsel

, the name of a sweet doughy pancake now most commonly made of matzo-meal and eaten at Passover.

The pasta and the almond pastry traditions merged in Sicily, resulting in foods with characteristics of both. As we saw above, early pastas were often sweet, and could be fried or baked as well as boiled. There is a kind of duality to many recipes from this period, which exist in both a savory cheese version and a sweet almond milk or almond-paste version that was suitable for the vast number of fast days (Lent, Fridays, and so on) that populated the medieval Christian calendar, when neither meat nor dairy could be eaten.

The almond pastry caliscioni, for example, had both almond and cheese versions. In fact, both versions still exist today. The almond descendant is called

calisson d’Aix

in Aix-en-Provence, where it is now a candy made of marzipan and dried fruit, iced with egg white and sugar. Calissons have been in Provence for a while;

the seer Nostradamus

(in his day job as an apothecary) published an early recipe for

callisson

in

1555, in between prophecies. As for the cheese descendant of caliscioni, you’ve likely eaten it; now called

calzone

, it is a kind of pizza stuffed with cheese and baked or fried.

Out of this culinary morass arises, circa 1279, the word

maccarruni

, the Sicilian ancestor of our modern words

macaroni

,

macaroon

, and

macaron

.

We don’t know whether

maccarruni

came from Arabic

, derives from another Italian dialect word (several dialect words have a root like

maccare

meaning something like “crush”),

or even comes from the Greek

makaria

.

But like other dough products of the period, it’s probable that the word

maccarruni

referred, perhaps in different locations, to two distinct but similar sweet doughy foods: one resembling gnocchi (flour paste with rosewater, sometimes egg whites and sugar, served with cheese), the other very much like a slightly fluffier marzipan (almond paste with rosewater, egg whites, and sugar).

The earliest recorded examples of maccarruni (or its descendant in Standard Italian,

maccherone

) refer to a sweet pasta. Boccaccio in his

Decameron

(around 1350) talks about maccherone as a kind of hand-cut dumpling or gnocchi eaten with butter and cheese. (Incidentally, this idea of lumpy gnocchi alternating with clumps of butter and cheese as metaphors for a hodgepodge of Italian and Latin was

the origin of the phrase “macaronic verse.”

) The fifteenth-century cookbook of Martino tells us that

Sicilian maccherone was made of

white flour, egg whites, and rosewater, and was eaten with sweet spices and sugar, butter, and grated cheese.

Now back to almond sweets, which by the 1500s had spread beyond Sicily and Andalusia to the rest of modern-day Italy and from there to France and then England. In 1552, in

a list of fantastical desserts in Rabelais’

Gargantua and Pantagruel

, we find hard written evidence that the word

macaron

meant a dessert. Shortly thereafter the name appears in English as

macaroon

(most sixteenth- and seventeenth-century French

words ending in –

on

are spelled with –

oon

when borrowed into English, like

balloon

,

cartoon

,

platoon

).

What did this sweet taste like?

Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery

, a handwritten cookbook that the first First Lady’s family had brought to the New World, contains the first known recipe. It was

probably written in the early 1600s

(notice the archaic spelling):

Take a pound & halfe of almonds, blanch & beat them very small in a stone morter with rosewater. put to them a pound of sugar, & y

e

whites of 4 eggs, & beat y

m

together. & put in 2 grayns of muske ground with a spoonfull or 2 of rose water. beat y

m

together till y

r

oven is as hot as for manchet, then put them on wafers & set them in on A plat. after a while, take them out. [y

n

when] y

r

oven is cool, set [y

m

in] againe & dry y

m

This recipe tells us that in the first half of the seventeenth century, the macaroon still had the rosewater and musk of its medieval Arab antecedent, lauz naj. We also see that macaroons were set on a wafer after baking, a historical remnant of the pastry shell of the earlier recipes.

naj. We also see that macaroons were set on a wafer after baking, a historical remnant of the pastry shell of the earlier recipes.

Even as this recipe was being written, however, modern French cuisine began to evolve out of its medieval antecedents, as cooks replaced imported medieval spices like musk with local herbs. The chef whose work is often considered

the turning point in this transition

was François Pierre de La Varenne, and the first completely modern recipe for macaroons comes from the 1652 edition of his cookbook,

The French Cook

, in which he eliminates orange water and rosewater from the earlier instantiations. He also eliminated the pastry shell; the only remnant of the former wafer is a piece of paper that the macaron sits on:

Macaron (“La maniere de faire du macaron”)

Get a pound of shelled almonds, set them to soak in some cool water and wash them until the water is clear; drain them. Grind them in a mortar moistening them with three egg whites instead of orange blossom water, and adding in four ounces of powdered sugar. Make your paste which on paper you cut in the shape of a macaroon, then cook it, but be careful not to give it too hot a fire. When cooked, take it out of the oven and put it away in a warm, dry place.

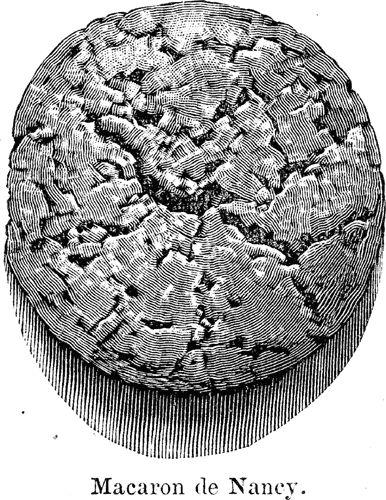

In France distinct variations for La Varenne–style macarons developed by the seventeenth century in places such as Amiens, Melun, Joyeuse, Nancy, and Niorts. In St.-Jean-de-Luz, a French Basque town just across the border from San Sebastian, Spain, we visited Maison Adam, the pâtisserie that claims to have supplied their golden-brown round “véritables macarons” to Anne of Austria when she came for the 1660 wedding of her son Louis XIV to the Infanta Maria Theresa of Spain. By the eighteenth century macarons were also commonly made in convents throughout France, both as a means of sustenance and, by selling them to the public, of financial support. After the French revolution, nuns who were ordered to leave their convents established macaron bakeries to support themselves in cities like Nancy, where the Maison des Soeurs Macarons is still in business, and Saint-Emilion, where

food writer Cindy Meyers writes

that the Fabrique de Macarons Blanchez bakery sells macarons according to the “Authentic Macaron Recipe of the Old Nuns of Saint-Emilion.”