The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn (39 page)

Read The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn Online

Authors: Alison Weir

Tags: #General, #Historical, #Royalty, #England, #Great Britain, #Autobiography, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Biography And Autobiography, #History, #Europe, #Historical - British, #Queen; consort of Henry VIII; King of England;, #Anne Boleyn;, #1507-1536, #Henry VIII; 1509-1547, #Queens, #Great Britain - History

T

HE

R

OYAL

C

HAPEL OF

S

T

. P

ETER AD

V

INCULA,

SHOWING THE SO-CALLED SCAFFOLD SITE

“The Queen’s head and body were taken to a church in the Tower.”

I

NSIDE

S

T

. P

ETER AD

V

INCULA

: A

NNE

B

OLEYN IS

BURIED BENEATH THE ALTAR PAVEMENT

“God provided for her corpse sacred burial,

even in a place as it were consecrate to innocence.”

M

EMORIAL PLAQUE SAID TO MARK THE LAST RESTING PLACE OF

A

NNE

B

OLEYN

It is more likely, however, that her body lies beneath the slab

commemorating Lady Rochford.

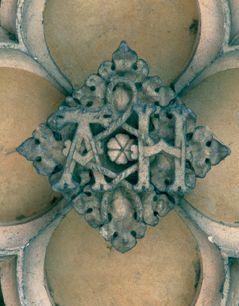

C

ARVED INITIALS OF

H

ENRY

VIII

AND

A

NNE

B

OLEYN IN THE VAULTING ABOVE

A

NNE

B

OLEYN’S

G

ATEWAY

, H

AMPTON

C

OURT

P

ALACE

This carving was overlooked in the

rush to replace Anne’s initials with

Jane Seymour’s.

Q

UEEN

E

LIZABETH

I’s

RING OF

c. 1575,

WITH ITS PORTRAIT OF

A

NNE

B

OLEYN

It is possible that Elizabeth secretly

commissioned a written defense of

her mother.

More Accused than Convicted

More Accused than ConvictedA

s yet, in accordance with the normal procedure in sixteenth-century treason cases, none of the accused were given full details of what was alleged against them in the indictments that had been drawn up, nor given any notice or means to prepare a defense. The first time they would hear the formal charges and any depositions, or “interrogatories,”

1

made by the witnesses was when they were brought into court, and then they would have to defend themselves as best they could, without benefit of any legal representation, which was forbidden to those charged with treason. They could not call witnesses on their own behalf—it is doubtful if many people would have dared come forward, anyway, to dispute a case brought in the name of “our sovereign lord the King”—and there was no cross-examination. All they could do was engage in altercation with their accusers. The law was heavily weighted against those suspected of treachery, and the outlook for Anne and the men accused with her was dismal. As Cardinal Wolsey once acidly observed, “If the Crown were prosecutor and asserted it, justice would be found to bring in a verdict that Abel was the murderer of Cain.”

2

It was to the further disadvantage of the accused that the law provided for a two-tier system of justice. Commoners had to be tried by the commissioners of oyer and terminer who brought the case against them, yet

those of royal or noble birth had to be tried in the court of the High Steward by a jury of their peers. Therefore there had to be two trials, and because of the practical difficulties involved—not least of which was the fact that the commissioners had to be present at both—they could not be held concurrently. Thus the outcome of the first trial would inevitably prejudice that of the second.

3

On Friday, May 12, Anne’s uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, was appointed Lord High Steward of England, a temporary office only conferred on great lords for the purpose of organizing coronations or presiding over the trials of peers, who were customarily tried in the court of the High Steward, which he himself convened. In this capacity, Norfolk would act as Lord President at the trials of the Queen and Lord Rochford.

Norfolk was at Westminster Hall that day as one of the commissioners who assembled there at the special sessions of oyer and terminer at which Norris, Weston, Brereton, and Smeaton were to be judged. As commoners, they would be tried separately from the Queen and Lord Rochford, who, by virtue of their high rank, had the right to be tried by their peers. All but one of the judges of the King’s Bench had been summoned to court, as well as a special jury of twelve knights, and they were joined by the members of the grand juries who had been appointed on April 24. Among them were the Lord Chancellor, who was “the highest commissioner,” and several lords of the King’s Council,

4

including Sir William FitzWilliam, who had been instrumental in obtaining confessions from Smeaton and Norris, and the Queen’s father, Thomas Boleyn, Earl of Wiltshire.

5

Chapuys heard that he was “ready to assist with the judgment,”

6

probably with an eye to his political survival. It may be significant that Edward Willoughby, the foreman of the jury, was in debt to William Brereton; Brereton’s death, of course, would release him from his obligations.

Other members of the jury were unlikely to be impartial. Sir Giles Alington was another of Sir Thomas More’s sons-in-law, and therefore no friend to the Boleyns, for many held Anne responsible for Sir Thomas’s execution. William Askew was a supporter of Lady Mary; Anthony Hungerford was kin to Jane Seymour; Walter Hungerford, who would be executed for buggery and other capital crimes in 1540, might well have needed to court Cromwell’s discretion; Robert Dormer was a conservative who had opposed the break with Rome; Richard Tempest was a creature of Cromwell’s; Sir John Hampden was father-in-law to William

Paulet, comptroller of the royal household; William Musgrave was one of those who had failed to secure the conviction for treason of Lord Dacre in 1534, and was therefore zealous to redeem himself; William Sidney was a friend of the hostile Duke of Suffolk; and Thomas Palmer was FitzWilliam’s client and one of the King’s gambling partners.

7

Given the affiliations of these men, and the unlikelihood that any of them would risk angering the King by returning the wrong verdict, the outcome of the trial was prejudiced from the very outset.

8

Legal practice apart, securing the conviction of the Queen’s alleged lovers was evidently regarded as a necessary preliminary to her own trial, while such a conviction would preclude the four men, as convicted felons, from giving evidence at any subsequent trial,

9

and the Queen from protesting that she was innocent of committing any crimes with them. Above all it would go a long way toward ensuring that her condemnation was a certainty. This, more than most other factors, strongly suggests that Anne and her so-called accomplices were framed.

The four accused were conveyed by barge from the Tower to Westminster Hall, where they were brought to the bar by Sir William Kingston and arraigned for high treason.

10

This vast hall had been built by William II in the eleventh century and greatly embellished by Richard II in the fourteenth. Lancelot de Carles, an eyewitness at all the trials, was at pains to describe the process of indictment, and “how the archers of the guard turn the back [of their halberds] to the prisoner in going, but after the sentence of guilty, the edge [of the axelike blade] is turned toward their faces.”

There is no surviving official record of the trials that took place on that day, only eyewitness accounts, which are frustratingly sketchy.

11

The accused were charged “that they had violated and had carnal knowledge of the Queen, each by himself at separate times,”

12

and that they had conspired the King’s death with her.

13

This was the first time the charges had been made public, or revealed in detail to the defendants, and the effect must have been at once sensational and chilling.

When the indictments had been read, the prisoners were asked if they would plead guilty or not, but only Mark Smeaton pleaded guilty to adultery,

14

confessing “that he had carnal knowledge of the Queen three times,”

15

and throwing himself on the mercy of the King, while insisting he was not guilty of conspiring the death of his sovereign. In the justices’

instructions to the Sheriff of London, to bring his prisoners to trial, which were dated May 12, 1536,

16

Smeaton’s name was erased, as if, having confessed, he was no longer thought worthy of examination,

17

so he was probably not subjected to questioning in court. The other three men, Norris included, pleaded not guilty,

18

and the jury was sworn in.