The Knight in History (15 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

KNIGHTING; THE SPONSOR GIRDS ON BELT AND SWORD, WHILE OTHER PARTICIPANTS PRESENT THE SPURS.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, MS. 11843, F.1)

As often happened when knighting took place on the eve of battle, time cut short the ceremony in William’s case. Before the knights and barons of the army, he donned a new mantle, the gift of his sponsor, the lord of Tancarville, who girded on his sword and gave him the

colée

.

13

There followed his first battle, in which English and Norman knights successfully defended Drincourt. William, lance broken in the first charge, his horse wounded, flung himself into the hand-to-hand fighting through the streets while the townspeople cheered from their windows.

14

At the feast that night celebrating the victory, a knight commented on William’s performance: William, he said, had fought to deliver the town rather than to take prisoners for ransom or to seize horses and equipment. He had behaved, in other words, like the ideal rather than the real knight. Such behavior was admired, but only to a point. The earl of Essex reminded William that a knight could not afford to disdain booty. “Marshal,” he said, “give me a gift, for love and for recompense.” “Surely,” agreed William, “what?” “A crupper, or a horse collar.” “But God bless me, I have never owned one in my whole life.” “Marshal, what are you saying? Today you had forty or sixty, before my own eyes! Will you refuse me?” The assembled company burst out laughing.

15

A truce concluded, William returned to Tancarville poorer than he had left, for his horse had died of its injuries. He could only afford to replace him with a cheap packhorse, and even that only by selling his new robe.

16

But the lord of Tancarville, deciding that William had learned his lesson, soon presented him with a warhorse on the occasion of the announcement of a tournament near Le Mans.

17

In it, his first, William enjoyed a brilliant success.

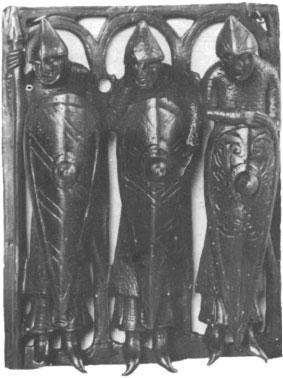

THE TOURNAMENT IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES CONSISTED OF A WAR-IMITATIVE MELEE RATHER THAN INDIVIDUAL JOUSTS.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, ADDIT. MS. 12, 228, F. 150B–151)

TWELFTH-CENTURY KNIGHTS CONTINUE TO WEAR LONG COATS OF MAIL AND CONICAL HELMETS AND TO CARRY KITE-SHAPED SHIELDS ROUNDED AT THE TOP IN A REPRESENTATION OF A BRONZE CASKET KNOWN AS THE “TEMPLE PYX.”

(BURRELL COLLECTION, GLASGOW MUSEUM)

The

History of William Marshal

is the major historical source for general information about the tournament before the thirteenth century, although presumably these occasions for sport and training date back to the eleventh century and even the tenth.

18

In William’s time and much later, the tournament did not involve individual jousting. Instead it consisted of a “melee” in which two sides fought a mock battle. Ground rules varied. Sometimes the knights vied for ransoms, arranged beforehand; sometimes the victors also captured horses, arms, and armor of the vanquished. In either case there was usually a prize for the knight who performed best. The two parties donned their armor in refuges at either end of the field, mounted, and galloped toward each other, lances couched. An unhorsed knight fought on foot with his sword. Armor was still light enough to permit this maneuver and to allow an unhorsed knight, provided he was not wounded, to rise from the ground. A hauberk weighed only twenty to thirty pounds, and even when pieces of plate armor were added, a knight carried no more than about forty pounds of iron, whose weight furthermore was well distributed.

19

The contest was not confined to the field; combatants ranged the countryside, which was supplied with refuges where they could rest and rearm. On occasion, foot soldiers joined in the melee. The fighting continued until dusk, when the knights assembled to award the prize and raise ransom money for their captive friends.

In his first tournament, William heeded the advice of his elders on looking out for himself. Overthrowing his first adversary, he seized his horse and exacted a pledge for ransom, then captured two more prisoners and confiscated their horses and equipment. By the tournament’s end, he had handsomely equipped himself and his retinue.

20

In William’s second tournament, which, with his lord’s permission, he attended alone, he unhorsed an opponent, successfully defended his prisoner against five other knights, and for his performance won a splendid warhorse from Lombardy.

21

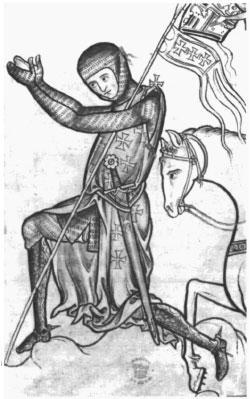

LATE TWELFTH-CENTURY ARMOR:

A CRUSADER WEARS A SURCOAT OVER MAIL, A ROUND HELMET, A MAIL COVERING FOR HIS NECK (VENTAIL) AND MAIL GAUNTLETS AND STOCKINGS.

(BRITISH LIBRARY, MS. 2A XXII, F. 220)

In the war-imitative spirit of the tournament, it was not regarded as unsporting for several knights to attack a single knight or to take prisoner a wounded man. William’s biographers record how at dinner during one tournament William caught sight of a knight of the opposing party who had fallen in the street and broken his leg. William “rushed outside, ran to the groaning knight, took him in his arms, armor and all, and carried him into the inn,” not to succor him, but to present him for ransom to his dinner companions with the words: “Here, take him to pay your debts!” The

History

applauds William’s knightly generosity on this occasion, as always, commenting that he “very willingly gave fine gifts and horses and

deniers

.”

22

TWELFTH-CENTURY TOURNAMENT:

KNIGHTS BATTLE AS LADIES WATCH. QUEEN GUINEVERE POINTS TO HER FAVORITE, LANCELOT.

(MORGAN LIBRARY, MS. 806, F. 262)

The mock battles were realistic enough to be dangerous, with numerous casualties, and even fatalities (one of William’s sons died in a tournament). Weapons were not blunted as in later practice. Violent behavior often overflowed into riot and even insurrection. Both the Church and lay authority strove to control such excesses.

Though the

History

pictures most of William’s tournaments as before masculine audiences, other sources suggest that already ladies attended, decked in the colors of their favorites and cheering them on with the “flirtatious behavior” ascribed by Geoffrey of Monmouth to the ladies of Camelot.

A colorful element of chivalry that grew out of the tournament soon after the First Crusade was the science and art of heraldry.

23

Helmets had grown more massive, with three forms becoming popular, round-topped, flat-topped, and conical, all fitted with a face guard with slits for vision and openings for ventilation. The evolution ultimately resulted in the “great helm,” a flat-topped cylinder completely enclosing the head and making the wearer unrecognizable with the visor closed.

24

Consequently identifying crests began to be added, becoming common in the thirteenth century along with insignia painted on shields and embroidered on surcoats or tunics (which were the original “coats of arms”). In time, as the insignia were elaborated into complex family histories, heraldry developed its own recondite vocabulary.

By the time William returned to England in 1167, his father and stepbrothers Gilbert and Walter had all died. The family estates and the office of marshal went to William’s remaining elder brother, John. Shortly after his return, William’s uncle, the earl of Salisbury, was summoned for an expedition to suppress a revolt in Poitou, part of the vast region of southwest France acquired by Henry II through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. William joined his uncle. In an ambush near Lusignan, southwest of Poitiers, his uncle was killed and William wounded and taken prisoner. He was ransomed by Queen Eleanor, and though the campaign was a failure, it thus brought William to the attention of the king.

25

In 1170, Henry II decided to crown his fifteen-year-old son Henry in the interest of preparing a peaceful succession without, however, relinquishing his own royal authority. The younger Henry was known henceforth to his English subjects as the Young King. To head his household and take charge of his military training, Henry II chose William Marshal.

26

The Young King was tall, fair-haired, and affable, and according to William’s biographers courteous, generous, and “the handsomest of all the princes in the world, whether Saracen or Christian.”

27

He was also a typical twelfth-century ruling-class youth, irresponsible, rebellious, pleasure-loving, spendthrift. His endless demands for money and power were accompanied by little taste or talent for administration.

28

In 1173 he quarreled violently with his father over the marriage settlement of his youngest brother, John, demanded Normandy, England, or Anjou as compensation, and sought the backing of his father-in-law, Louis VII of France, as well as that of the barons of England and Normandy. Fearing an attempt to depose him, Henry II started north from Limoges, where the quarrel had taken place, taking the Young King with him. At the castle of Chinon the younger Henry slipped away at night with his household. By this act of rebellion, he declared war against his father, and to fight it, arranged to be knighted. King Louis sent his brother and other barons to the ceremony, but the Young King chose William Marshal to gird on his sword and give him the ritual

colée

.

29