The Judgment of Paris (56 page)

T

HE BOMBARDMENT OF Paris by the Prussians lasted for almost three weeks. Some 400 shells fell on the city each evening as the Prussians fired their guns after ten o'clock at night in order to starve the besieged Parisians of sleep as well as food. Since the bulk of the artillery was positioned on the heights of Châtillon, five miles south of where the Seine flowed through the center of Paris, virtually all of the mortars fell on the Left Bank. "The Prussian shells have already reached as far as the Rue Soufflot and the Place Saint-Michel," Manet wrote to his wife a week after the bombardment started.

1

The Chapel of the Virgin in Saint-Sulpice was struck by a mortar. So were the Gare d'Orleans, with its balloon factory; the Jardin des Plantes, where a collection of orchids was destroyed; and a school in the Rue de Vaugirard, where a single shell killed five young children.

Residents of the Left Bank hastily fled across the river, clutching a few meager possessions and looking, as Gautier observed, like "a migration of Indians carrying their ancestors rolled in bison skins."

2

Gautier himself was in the firing line, having fled from his house in Neuilly to what he thought was the greater safety of the Faubourg Saint-Germain. Both Manet and Meissonier, however, occupied securer quarters on the Right Bank, more than a mile away from where the nearest shells had fallen. Even so, the noise was deafening. "The cannonade was so heavy during the night," Manet wrote to Suzanne, "that I thought the Batignolles was bombarded." Three days later he added, plaintively: "The life I am leading is unbearable."

3

The Prussian guns finally fell silent on January 27, when the Government of National Defense agreed to an armistice. The Siege of Paris had lasted a total of 130 days. "Holding out was no longer possible," Manet wrote to Suzanne. "People were starving to death and there is still great distress here. We are all as thin as rails."

4

The armistice was officially signed at the Palace of Versailles on the twenty-eighth, where less than two weeks earlier another ceremony had taken place. The south German states of Bavaria, Baden and Württemberg had agreed to join the German Confederation, which thereafter became known as the Deutsches Reich, or German Empire, a federal state governed by Wilhelm. This unification of Germany was celebrated on January 18 as Wilhelm was proclaimed Emperor, or Kaiser, in a ceremony staged—humiliatingly for the French—in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. "That really marks the end of the greatness of France," despaired Edmond de Goncourt after reading of Wil-helm's coronation in a newspaper.

5

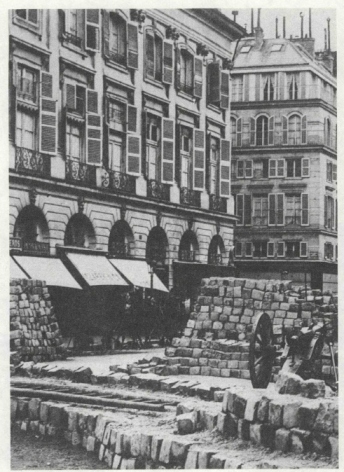

Rue

Castiglione during the siege of Paris, 1871

Manet observed the end of the siege by treating himself to a choice cut of beef—for which he paid seven francs a pound—and cooking

a pot-au-feu,

the nourishing dish of boiled beef and vegetables ("but naturally with no vegetables," he complained)

6

known as

le plat qui fait la France

("the dish that made France"). He then began preparations for the 400-mile journey south to the Pyrenees for a reunion with Suzanne, his mother and Léon. His joy at being able to see his family again was tempered by the sad news, received early in February, that Frédéric Bazille, the great friend of Claude Monet, had been killed at the end of November while serving with the Zouaves. Dying a few months short of his thirtieth birthday, Bazille was tragically denied the chance to further explore his brilliant talents.

Meissonier had a much shorter journey to make, but he too was in mourning as he left Paris. He arrived at the Grande Maison, sometime early in February, suffering from "the bitterest sorrow I have ever felt."

7

A young friend and protégé, Henri Regnault, winner of the Prix de Rome in 1866 and of gold medals at the Salons of 1869 and 1870, had been killed in a disastrous sortie by the National Guard at Buzenval, seven miles west of Paris, on January 19. Meissonier, who spoke to the young painter on the night before his death, had seen in Regnault the future of French art. He had personally recovered his body from the muddy battlefield and then a few days later delivered the funeral oration. His words were inspirational: "Let us work again," he had exclaimed. "The time is short. We have no eternity in which to re-create our country."

8

But the young man's death left him consumed by a furious hatred for the Prussians. He was therefore displeased in the extreme to discover, upon returning to Poissy, that the Grande Maison had been turned into a barracks for Prussian soldiers. Sixty of them had been living in the house since the start of the siege, with no plans to depart. Meissonier thereby found himself compelled to share his accommodation with the despised enemy.

Other unpleasant surprises awaited Meissonier's return. Though he had been able to save Blocus and Lady Coningham from the slaughterhouse, one of his horses had been appropriated by the Prussians, who had furthermore taken, and presumably butchered, his cows. Several of his other horses had been requisitioned by the French army; among them was Bachelier, the gray stallion that had appeared in so many of his paintings and sketches. He never saw Bachelier again, and sometime after his return to Poissy he inscribed on one of his 1865 sketches of the animal the words: "My poor Bachelier, taken by the Army of the Loire, 27 January 1871."

9

One of the few consolations for Meissonier as he returned to Poissy was a reunion with Elisa Bezanson, by then thirty years old, still unmarried, and still completely devoted to him. And, for what seems to be the first time, he began a painting that featured her. To escape from the Prussians occupying his house, Meissonier shut himself away in his studio and, in the words of the critic Jules Clarétie, "threw upon the canvas the most striking, the most vivid, the most avenging of allegories."

10

Having begun sketches for

The Siege of Paris

while staying with Francis Petit, he portrayed the tall, robust Elisa as the figure of Paris standing enveloped, in the words of Clarétie, "in a veil of mourning, defending herself against the enemy, with her soldiers and her dying grouped around a tattered flag." Victims of the siege lay sprawled at her feet—soldiers, National Guardsmen, women, children, a horse—while a Prussian eagle, with "wan and haggard Famine" at its side, hovered in the air above them. "I will put all our sufferings, all our heroism, all our hearts—my very soul into it," declared Meissonier, who described the painting as an act of revenge against the conquering Prussians.

11

Passionate he may have been about his new work, but Meissonier approached

The Siege of Paris

(plate 7A) with his typical painstaking devotion. He made a wax model for the dying horse, while for the figure of Henri Regnault, whom he depicted leaning against the allegorical figure of Paris, he borrowed the greatcoat which the painter had been wearing when he was shot in the head. And likewise for the figure of Brother Anselme, one of the Brothers of the Christian Doctrine whose job was to retrieve bodies from the field of battle, he borrowed the black gown worn by the cleric when he was killed by a Prussian bullet.

12

The Siege of Paris

recalls

The Last Day of Corinth.

Tony Robert-Fleury's triumph from the 1870 Salon. But it also evokes Meissonier's own earlier work,

Remembrance of Civil War,

the painting (so admired by Delacroix) that had been removed from the 1850 Salon on orders from the government because its "omelette of men" showed the horrors of warfare in such scarifying detail.

The Siege of Paris

emphasized, even more than

Friedland,

Meissonier's turn from his lucrative but—in light of recent political events—irrelevant musketeer subjects to a style of painting that would be grander in both physical scale and emotional impact. This was no time, he claimed, "to paint little figures."

13

Artistic monumentality was, he believed, the order of the day. "I want to execute this painting large as life!" he said of

The Siege of Paris,

even going so far as to entertain hopes of executing it as a mural: "Who knows? Perhaps this is the picture that will be in the Panthéon some day."

14

But Meissonier still had a very long way to go before he could project his noble vision on such elevated walls, since the sketch over which he labored in the months following his return to the Grande Maison measured—in typical Meissonier fashion—less than a foot square.

Manet was reunited with Suzanne, his mother and Léon on February 12 1871, five months after he had bade them farewell. Oloron-Sainte-Marie, where the family had spent their exile, was an old wool town, famous for manufacturing berets, that perched on a wooded bluff overlooking the junction of two swift-flowing rivers. Suzanne seems to have spent much of her time there arguing with her mother-in-law. The two women had never enjoyed cordial relations, and their enforced exile only led to further mutual aggravation. According to Eugénie Manet, Suzanne had written dozens of letters to Édouard during the siege, documenting "a thousand complaints about me. . . . Her jealousy was always there, against me!"

15

Luckily for Manet, none of these missives made it through the Prussian blockade.

Manet did not remain for long in Oloron-Sainte-Marie. After less than two weeks in the Pyrenees he made the no-mile trip north to Bordeaux, where, craving the sea rather than the mountains for his recuperation, he arranged the rental of a villa on the coast. Bordeaux was, temporarily at least, France's new seat of government, with the National Assembly having convened in the city's Grand Théâtre following national elections in the first week of February

*

These elections showed the divisions between Paris and much of the rest of the country. More than 400 of the 768 seats were won by monarchists—deputies who wished to restore to the throne of France one of the two Pretenders, either the Comte de Chambord (the grandson of King Charles X) or the Comte de Paris (the grandson of King Louis-Philippe). The voters of Paris, on the other hand, had elected a number of deputies with strong republican and socialist credentials, such as Victor Hugo, Henri Rochefort and Louis Blanc, the man who coined the phrase "to each according to his needs." The brother of the art critic Charles Blanc, he was known in England, to which he had been exiled by Napoléon III, as the "Red of the Reds."

16

Adolphe Thiers, likewise elected in Paris, was named "chief of the executive power of the French Republic" and given the authority to negotiate the terms of the surrender with Otto von Bismarck. These terms proved extremely harsh. On February 26, hours before the armistice was due to expire, Thiers agreed to cede most of Alsace and part of Lorraine to the Germans; to pay an indemnity of five billion francs; to permit 500,000 German troops to remain on French soil until this indemnity was paid; and to allow the Germans a victory parade through the streets of Paris. When Thiers presented the treaty for ratification in the National Assembly two days later, many deputies, especially the socialists and republicans elected in Paris, were outraged by what they saw as a betrayal by Thiers and a humiliation by Bismarck. Manet was equally unimpressed with Thiers. After witnessing the proceedings of this new National Assembly, he wrote biliously to Félix Bracquemond about "that little twit Thiers, who I hope will drop dead one day in the middle of a speech and rid us of his wizened little person."

17

The crushing terms of the treaty were ratified on the first of March.

Manet was reunited in Bordeaux with Émile Zola. Since escaping to Marseilles in September, Zola had launched a newspaper,

La Marseillaise,

which he intended to serve as a voice of the proletariat. However, this organ ceased publication in December when, ironically, the printers struck for higher wages, an action that Zola, turning strike-buster, tried unsuccessfully to overcome by engaging a team of cut-rate printers from Aries. With his career as a newspaper proprietor thwarted, he began cultivating plans to secure for himself the post of Subprefect for Aix-en-Provence, and to that end he had gone to Bordeaux to lobby officialdom. He was offered a lesser plum, Subprefect of Quimperlé in Brittany, which he imperiously declined as being "too far away and too grim."

18

Eventually he accepted the post of secretary to an elderly and reputedly senile left-wing deputy in the National Assembly. He was also reporting on the National Assembly for

La Cloche

and fretting about the refugees occupying his apartment in Paris. "Are there any broken dishes?" he wrote to a friend in Paris. "Has anything been ransacked or stolen?"

19