The JOKE (18 page)

From this they conclude that the folk song is not an original artistic form. It is merely a derivative of formal music.

Now, that may have been the case in Bohemia, but the songs we sing in Moravia can't be explained in this way. Look at their tonality. Baroque music was written in major and minor keys. Our songs are sung in modes that court orchestras never dreamed of!

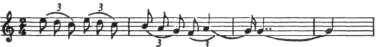

For example, the Lydian. The scale with the raised fourth. It always evokes in me nostalgia for the pastoral idylls of antiquity. I see the pagan Pan and hear his pipes: Baroque and Classical music paid fanatical homage to the orderliness of the major seventh. It knew no other path to the tonic than through the discipline of the

leading tone.

It was frightened of the minor seventh that stepped up to the tonic from a major second below. And it is precisely this minor seventh that I love in our folk songs, whether it belongs to the Aeolian, Dorian, or Mixolydian. For its melancholy and

pensiveness. And because it abjures the foolish scamper toward the key note with which everything ends, both song and life:

But there are also songs in tonalities so curious that it is impossible to designate them by any of the so-called ecclesiastical modes. They take my breath away: Moravian songs are, in terms of tonality, unimaginably varied. Their musical thought is mysterious. They'll begin in minor, end in major, hesitate among different keys. Often when I have to harmonize them, I just do not know how I am to understand the key.

And they are similarly ambiguous when it comes to rhythm. Especially the long-drawn-out ones that are not used for dancing. Bartok called them

parlando

songs. Their rhythm cannot be written down in our notation system. Or let me put it differently. From the vantage point of our notation all folk singers sing their songs in a rhythm that is imprecise and wrong.

How can that be explained? Janacek maintained that the complexity which makes it impossible for us to do justice to all the nuances of the rhythm is due to the various fleeting moods of the singer. It depended on where they were singing, when they were singing, how they felt when they were singing. The folk singer reacted in his singing to the color of the flowers, to the weather, to the sweep of the countryside.

But isn't that just a bit too poetic an explanation? During my first year at the university a professor told us of an experiment he had conducted. He'd asked several folk artists to interpret the same rhythmically indefinable song independently of one another.

Measuring the results on accurate electronic equipment, he ascertained that their singing was exactly the same.

The rhythmical complexity of the songs is therefore not due to any imprecision or imperfection or to the mood of the singer. It has its own mysterious laws. In one kind of Moravian dance song, for example, the second half of the measure is always a fraction of a second longer than the first half. Now, how can such rhythmic complexity be notated?

The metrical system used by formal music is based on symmetry. A whole note divides into two halves, a half into two quarters, a measure is divided into two, three, or four equal beats. But what to do with a measure that is divided into two beats of unequal length? For us today, our biggest headache is how to notate the original rhythm of Moravian songs.

One thing at least is clear. Our songs cannot be derived from Baroque music. Bohemian songs, maybe. Perhaps. Bohemia always had a higher level of civilization, and there was greater contact between town and country villagers and court. Moravia had its great houses too. But the world of the peasants was far more remote by reason of its primitiveness. Here, no country folk went to play in court orchestras. These conditions enabled us to preserve folk songs from the oldest of times. This explains why they are so enormously varied. They derive from different phases of their long, slow history.

So when you come face to face with the whole of our folk music culture, it's like having a woman from

The Thousand and One Nights

dancing before you and gradually throwing off veil after veil.

Look! The first veil. The cloth is rough and patterned with trite designs. These are the youngest songs, of the last fifty, seventy years. They came to us from the west, from Bohemia. Brought by the teachers who taught the children to sing them in our schools.

For the most part,

they are songs in major keys, of a common West European type, only slightly adapted to our rhythms.

And the second veil. Much more colorful. The songs of Hungarian origin. They came with the encroachment of the Magyar language into the Slavic regions of Hungary.

Gypsy groups spread them far and wide throughout the nineteenth century. Everyone knew them. Czardases and recruiting songs with that special syncopated rhythm.

As the dancer throws off this veil, there is another one! They are the songs of the native Slav population from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

But the fourth veil is even more beautiful. These are even older songs. They go back as far as the fourteenth century, when the Wal-lachians made their way to us across the Carpathians from the east and southeast. Their shepherd and brigand songs know nothing of chords and harmony. They are conceived purely in melodic terms, in archaic tonalities.

Pipes and fifes lend a special character to the melodies.

Once this veil has fallen away, there is no other beneath it. The dancer is dancing completely naked. These are the oldest songs of all. They stretch back into ancient pagan times. They are based on the oldest system of musical thought. On the system of four tones, on the tetrachord. Mowing songs. Harvest songs. Songs tightly bound up with the rites of the patriarchal village.

Bartok has shown that on this oldest of levels the songs of Slovakia, Moravia, Hungary, and Croatia resemble each other to the point of being indistinguishable. When you imagine this territory, the first grand Slavic dominion from the ninth century rises before your eyes, the Great Moravian Empire. Its borders were swept away a thousan4 years ago, yet they remain imprinted to this day in this most ancient stratum of folk songs.

The folk song or folk rite is a tunnel beneath history, a tunnel that preserves much of what wars, revolutions, civilization have long since destroyed aboveground. It is a tunnel through which I see far into the past. I see Rostislav and Svatopulk, the first Moravian princes. I see the ancient Slavic world.

But why go on speaking only about the Slavic world? Once we racked our brains to make sense of an enigmatic folk song text. It mentioned hops in some unclear connection with a cart and a goat. Someone is riding on a goat, someone else in a cart. Then hops are praised for their power of turning maidens into brides. The folk singer who sang it for us had no idea what it meant either. The tenacity of age-old tradition had preserved a combination of words now lacking all trace of intelligibility. In the end there turned out to be only one possible explanation: the ancient Greek Dionysian festival. A satyr on a billy goat and a god grasping his thyrsus wound round with hops.

Classical antiquity! I couldn't believe it. But then, at the university, I studied the history of musical thought. The structure of our oldest folk songs is indeed analogous to that of ancient Greek music. The Lydian, Phrygian, and Dorian tetrachords. The concept of the descending scale, whose final tone is the highest and not the lowest—the latter becoming the key tone only when music began to think harmonically. So our oldest songs belong to the same era of musical thought as the songs sung in ancient Greece. They preserve classical antiquity for us.

5

At supper tonight I kept seeing Ludvik's eyes turn away from me. And I felt myself clinging all the more to Vladimir. Suddenly I was afraid I'd been neglecting him. That I'd never really succeeded in drawing him into my world. After supper Vlasta stayed in the kitchen, and I went into the living room with Vladimir. I tried to tell him about folk songs. It didn't work. I felt like a schoolteacher. I wondered whether I was boring him. Of course, he sat there silently looking as if he were listening. He's always been a good boy.

But how can I tell what's actually going on in that head of his?

I'd been torturing him for quite a while with my lecture when Vlasta stuck her head into the room and said it was time for bed. What could I do? She was the heart and soul of the house, its calendar and clock.

We won't argue. Off to bed, my boy, good night.

I left Vladimir in the room with the harmonium. He sleeps there on the sofa with the metal legs. I sleep next door beside Vlasta in the marriage bed. I won't go to bed yet. I'd twist and turn and worry whether I was waking Vlasta. I'll take a breath of fresh air. It's a warm night. The garden of the old one-story dwelling where we live is full of old-fashioned rural smells. There's a wooden bench under the pear tree.

Damn Ludvik. Why did he show up today of all days? I'm afraid it's a bad omen. My oldest friend! This was where we used to sit as boys, under this very tree. I liked him from the start. When we first went to the same school. He had more brains in his little finger than the rest of us put together, but he never showed off. He couldn't have cared less about either school or teachers, and he enjoyed doing anything that was against the regulations.

Why did the two of us become such close friends? Kismet, most likely. We were both half orphans. Mama died in childbirth. And Ludvik's father, a bricklayer, was hauled off to a concentration camp by the Germans. Ludvik was thirteen at the time. He never saw him again.

Ludvik was the eldest son. And by then, he was also the only one, because his younger brother had died. After his father's arrest, mother and son were left alone. They barely managed to make ends meet. School fees were high. For a while it seemed he would have to quit.

But at the eleventh hour salvation came.

Ludvik's father had a sister who had married a rich local builder well before the war.

Afterwards she had lost almost all contact with her bricklayer brother. But when they took him away, her patriotic heart was suddenly inflamed. She told her sister-in-law that she would support Ludvik. She herself had only one somewhat backward daughter, and Ludvik with his talents made her envious. Not only did she and her husband assist him materially, but they invited him to their house daily. They introduced him to the cream of local society. Ludvik had to appear grateful to them, because his studies depended on their support. Well, he couldn't bear them. Their name was Koutecky, and from that time on we used it to refer to anyone pompous and pretentious.

Madame Koutecky looked down her nose at Ludvik's mother. She'd always felt her brother had married beneath him. Her brother's arrest did nothing to change her mind.

The heavy artillery of her charity was aimed at Ludvik and Ludvik alone. She saw in him her own flesh and blood and longed to make him over into her son. The existence of her sister-in-law she regarded as a regrettable mistake. She never invited her to her house.

Ludvik saw all this, gritting his teeth. He was ripe for rebellion. But his mother would beg him tearfully to be sensible.

That was one reason why he so liked coming to our place. The two of us were like twins.

Papa loved him almost more than he loved me. It made him happy to see Ludvik devouring the books in his library one by one. When I started playing in the jazz band, Ludvik wanted to play too. He bought a cheap clarinet at the open market and could hold his own on it in no time. We played jazz together and together joined the cimbalom band.

Towards the end of the war the Kouteckys' daughter got married.

Ludvik's aunt decided to make it a big event. She wanted to have five pairs of bridesmaids and groomsmen behind the bride and groom. She forced on Ludvik the duty of taking one of these roles, giving him the eleven-year-old daughter of the local pharmacist as a partner. Ludvik lost all sense of humor. He was embarrassed to play the fool at a wedding masquerade of provincial snobs. He considered himself an adult and was ashamed to offer his arm to a mere child. He was furious at being displayed as the Kouteckys' charity case. Furious at being forced to kiss the cross during the ceremony after everyone had slobbered over it. That evening he deserted the festivities to join us in our back room at the local inn. We'd been playing music, and now, gathered around the cimbalom, we were drinking and started to tease him. He lost his temper and proclaimed that he hated the bourgeois. Then he cursed the marriage ceremony and said he spat on the Church and was going to leave it.