The Jewel That Was Ours (13 page)

Read The Jewel That Was Ours Online

Authors: Colin Dexter

In the Oxford Story Gift Shop, the group had stayed quite some time,

examining

aprons, busts, chess-sets, Cheshire cats, cufflinks, games, gargoyles, glassware, jewellery, jigsaws, jugs, maps, pictures, postcards, posters, stationery, table-mats, thimbles, videos - everything a tourist could wish for.

'Gee! With

her

feet, how Laura would have loved that ride!' remarked Vera Kronquist. But her husband made no answer. If he were honest he was not wholly displeased that Laura's feet were no longer going to be a major factor in the determination of the tour's itineraries. She was always talking about lying down; and now she

was

lying down. Permanently.

'Very good,' said Phil Aldrich as he and Mrs Roscoe and the Browns emerged through the exit into Ship Street.

'But the figures there - they weren't nearly as good as the ones in Madame Tussaud's, now were they?'

‘No, you're quite right, Janet,' said Howard Brown, as he gently guided her towards Cornmarket and back towards The Randolph.

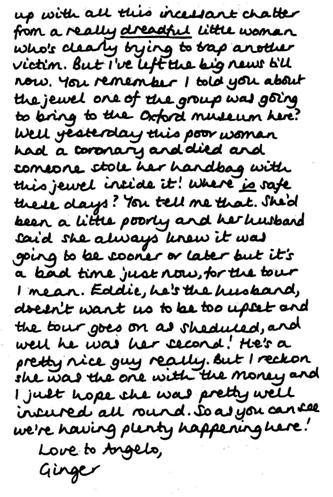

When, five days later, Mrs Georgie Bonnetti received her sister's interesting letter, she was a little disappointed (herself a zealous Nonconformist) that with neither cartridge from the double-barrelled rifle had her sister succeeded in hitting the saintly founder of Methodism. (The unbeliever Morse would have been rather more concerned about the other four mis-spellings.)

Clever people seem not to feel the natural pleasure of bewilderment, and are always answering questions when the chief relish of a life is to go on asking them

(Frank Moore Colby)

After his

in situ

briefing outside Balliol, Downes left the scene of the barbarous burnings and strolled thoughtfully along to Blackwells. An hour and a quarter (Ashenden had suggested) for The Oxford Story; then back to The Randolph where he and Sheila Williams and Kemp (the man would always remain a surname to Downes) had agreed to hold the question-and-answer session with the Americans. Downes sometimes felt a bit dubious about 'Americans'; yet like almost all his colleagues in Oxford, he often found himself enjoying actual Americans, without those quotation marks. That morning he knew that as always some of their questions would be disturbingly naive, some penetrating, all of them

honest.

And he approved of such questions, doubtless because he himself could usually score a pretty point or two with answers that were honest: quite different from the top-of-the-head comments of some of the spurious academics he knew. People like Kemp.

After spending fifty minutes browsing through the secondhand books in Blackwell's, Downes returned to The Randolph, and was stepping up the canopied entrance when he heard the voice a few yards behind him.

'Cedric!'

He turned round.

'You must be deaf! I called along the road there three or four times.'

'I

am

deaf - you know that.'

'Now don't start looking for any sympathy from me, Cedric! What the hell! There are far worse things than being deaf.'

Downes smiled agreement and looked (and not without interest) at the attractively dressed divorcee he'd known on and off for the past four years. Her voice (this morning, again) was sometimes a trifle shrill, her manner almost always rather tense; but there were far worse things than . . .

'Time for a drink?' asked Sheila - with hope. It was just after eleven.

They walked together into the foyer and both looked at the noticeboard in front of them:

HISTORIC CITIES TOUR ST JOHN'S SUITE

11.30 a.m.

'Did you hear me?' continued Sheila. 'Pardon?'

'I said we've got almost half an hour before—'

'Just a minute!' Downes was fixing an NHS hearing-aid to his right ear, switching it on, adjusting the volume - and suddenly, so clearly, so wonderfully, the whole of the hotel burst into happily chattering life. 'Back in the land of the living! Well? I know it's a bit early, Sheila, but what would you say about a quick snifter? Plenty of time.'

Sheila smiled radiantly, put her arm through his, and propelled him through to the Chapters Bar: 'I would say "yes", Cedric. In fact I think I would say "yes" to almost anything this morning; and especially to a Scotch.'

For a few delightful seconds Downes felt the softness of her breast against his arm, and perhaps for the first time in their acquaintanceship he realised that he could want this woman. And as he reached for his wallet, he was almost glad to read the notice to the left of the bar: 'All spirits will be served as double measures unless otherwise requested.'

They were sitting on a beige-coloured wall-settee, opposite the bar, dipping occasionally into a glass dish quartered with

green olives, black olives, cocktail onions, and gherkins - when Ashenden looked in, looked around, and saw them.

'Ah - thought I might find you here.'

'How is Mr Stratton?' asked Sheila.

'I saw him at breakfast - he seems to be taking things remarkably well, really.'

'No news of

...

of what was stolen?'

Ashenden shook his head. 'Nobody seems to hold out much hope.'

'Poor Theo!' pouted Sheila. 'I must remember to be nice to him this morning.'

'I, er,' Ashenden was looking decidedly uncomfortable: 'Dr Kemp won't be joining us this morning, I'm afraid.'

'And why the hell

not?

’

This from a suddenly bristling Sheila.

'Mrs Kemp rang earlier. He's gone to London. Just for the morning, though. His publisher had been trying to see him, and with the presentation off and everything—'

'That was this

evening’

protested Downes.

'Bloody nerve!' spluttered Sheila. 'You were here, John, when he promised. Typical! Leave Cedric and me to do all the bloody donkey-work!'

'He's getting back as soon as he can: should be here by lunchtime. So if - well, I'm sorry. It's been a bit of a disappointment for the group already and if you . . .'

'One condition, John!' Sheila, now smiling, seemed to relax. And Ashenden understood, and walked to the bar with her empty glass.

The tour leader was pleased with the way the session had gone. Lots of good questions, with both Sheila Williams and Cedric Downes acquitting themselves

magna cum laude,

especially Downes, who had found exactly the right combination of scholarship and scepticism.

*

*

*

It was over lunch that Sheila, having availed herself freely of the pre-luncheon sherry (including the rations of a still-absent Kemp), became quite needlessly cruel.

‘Were you an undergraduate here - at Arksford, Mr Downes?'

'I was here, yes. At Jesus - one of the less fashionable colleges, Mrs Roscoe. Welsh, you know. Founded in 1571.'

'I thought Jesus was at Cambridge.'

Sheila found the opening irresistible: 'No, no, Mrs Roscoe! Jesus went to Bethlehem Tech.'

It was a harmless enough joke, and certainly Phil Aldrich laughed openly. But not Janet Roscoe.

'Is that what they mean by the English sense of humour, Mrs Williams?’

'Where else would he go to do carpentry?' continued Sheila, finding her further pleasantry even funnier than her first, and laughing stridently.

Downes himself appeared amused no longer by the exchange, and his right hand went up to his ear to adjust an aid which for the past few minutes had been emitting an intermittent whistle. Perhaps he hadn't heard . . .

But Janet was not prepared to let things rest. She had (she knew) been made to look silly; and she now proceeded to make herself look even sillier. 'I don't myself see anything funny in blasphemy, and besides they didn't have colleges in Palestine in those days.'

Phil Aldrich laid a gently restraining hand on Janet's arm as Sheila's shrill amusement scaled new heights: 'Please don't make too much fun of us, Mrs Williams. I know we're not as clever, some of us, as many of you are. That's why we came, you know, to try to learn a little more about your country here and about your ways.'