The Jaguar Smile (13 page)

Authors: Salman Rushdie

Amidst these barbed tales of old Managua, I remembered another instance in which Cardenal had adapted an old poem to a new purpose. He had drafted a poem about the death of Sandino, and the fact that his grave was unknown. Then, in 1954, an attempt to capture Anastasio Somoza García, the then dictator, ended in failure. One of the conspirators, Pablo de Leal, had his tongue cut out before being killed. It is said that another, Adolfo Báez Bone, was castrated. The main torturer was Anastasio Somoza Debayle, who would be the last dictator of the line. When Cardenal heard the news, he decided to make Báez Bone the subject of his poem instead of Sandino:

Epitaph for the Tomb of Adolfo Báez Bone

They killed you and didn’t say where they buried

your body,

but since then the entire country has been your

tomb,

and in every inch of Nicaragua where your body

isn’t buried,

you were reborn.

They thought they’d killed you with their order of

Fire!

They thought they’d buried you

and all they had done was to bury a seed.

When the guests had departed and the dust had settled, I asked Daniel Ortega a few more questions. First, though, he wanted to give me his views on

La Prensa

. ‘They can do anything they like, but they must not advocate support for Reagan and the Contra. That’s the mark. They went over it. What could we do? Put them on trial? That would have created too much negative attention. So all we could do was close the paper.’

I said: ‘I want to be clear about this. I’ve been told that the problem with

La Prensa

was CIA funding and control. But now you’re saying it was the editorial line.’

Ortega replied: ‘There’s a war on. In peacetime, if

La Prensa

wants to take CIA money, which it did, and push the US line, that’s fine. If it wants to attack the Frente, that’s also fine. But now it’s different. The enemy uses the paper.’ The internal front argument again. The fear of a repetition of Chile. Amongst all Nicaragua’s phantoms, I thought, there were two darker spectres. Edén Pastora, the skeleton in the cupboard; and Salvador Allende, who was possibly the most important political figure in Nicaragua, after Sandino, anyway.

I asked: ‘I’ve heard many people saying they think a US invasion is inevitable. What’s your view?’

Ortega: ‘There is a certain fatalism here about this. The situation at the frontier is very tense. Many things could trigger an invasion. For example, in March, we crossed over the Honduras frontier to attack Contra camps. The Honduras government knew we were there, they knew why, they said nothing. It was OK. But the US made a great fuss, moving their personnel and weaponry to the front at a time when we were already falling back. Finally the Honduras government did send us a protest, because of the intense US pressure on them to do so. Now the situation is worse than it was then, because soon, US advisers will be legally allowed to be present by the Congress. So if we shoot down a helicopter and a US citizen dies, it could be provocation. Actually, in March, a US citizen was killed, but since he was there illegally – illegally according to the Congress – Reagan couldn’t make anything out of it.

‘On the seventh anniversary we deliberately held the Acta at Estelí, to show our determination. After we repelled the two Contra forces that had massed on the frontier, the Honduras government was afraid that, as in March, we would go after them across the border, in “hot pursuit”. They actually contacted us to warn us that the US had decided that if we did, that was it, they would attack us. It was very clear. So it could happen at any time.’

I asked: ‘Now that the US is spending so heavily to “buy off” your neighbours, do you agree that you are gradually becoming isolated?’

Ortega: ‘It’s not so easy for the US to isolate us. The people of Central America know that a war here would spread, would become a Central American war. The US had been trying to persuade Honduras, Costa Rica and Salvador to break with us,

as you know, and they may succeed. But even Costa Rica, in spite of everything, still has reservations.’

I asked: ‘Who was responsible for the attack on the Contra in Tegucigalpa today?’

Ortega: ‘We think some guerrillas may have done it. But that fifty Contra leaders could meet so near the President’s house: this has disturbed the people of Honduras.’

I asked: ‘On the economy: considering the great pressure it’s under, how close is it to total collapse?’

Ortega: ‘In this special situation, war, we believe that the idea of collapse is not appropriate. You must understand that our people have never been used to great affluence, and minimum subsistence levels are being maintained. We are even slowly improving our agrarian and industrial base.’

I asked: ‘But with inflation at 500 per cent, a more or less total strike of investment capital, and a fiscal deficit that represents forty per cent of government spending, are you really saying you can survive indefinitely?’ The latest economic indicators were pretty terrible: figures released by the Economic Commission on Latin America showed a three per cent drop in gross domestic product, a five per cent fall in production in manufacturing industry, a vast trade gap. Cotton production had been badly hit by disease and weather and had fallen by nineteen per cent. Low world prices, as well as drought, had meant a reduced income from coffee, sugar and cotton exports (most of the coffee crop had been sold in advance, at 1985 rates, and had therefore missed out on the rise in coffee prices in 1986.)

Ortega gave a somewhat sheepish laugh. ‘Well, we have managed so far, and let’s say we hope to go on. We subsidize the price of a number of essential commodities, basic grains, oil, soap, beans, agricultural tools. All in limited quantities, of course. The rest of the prices, we have to let them rise, and

they have gone up enormously. But at subsistence level the inflation is controlled.’

I asked: ‘You make a great deal, understandably enough, of the Hague judgment. But many Western commentators play it down, setting the

La Prensa

closure and the expulsion of the priests against it, “balancing” it, so to speak. How can you hope to win the argument when, rightly or wrongly, the Western media simply don’t see the Hague rulings the way you do, and don’t give it the column-inches?’

Ortega replied: ‘We know there is a lot of sympathy for our case among the people of the United States and Europe. We have to continue to take our case to the people.’ More televised jogging, more chat-show politics. The twentieth century was a strange place.

It was one o’clock in the morning; time to leave. As I said goodbye to Rosario Murillo, she seemed already to be bracing herself for the Chinese takeaways of Manhattan. ‘The one thing I always look forward to in New York,’ she said bravely, ‘is the yoghurt.’

‘Really?’

‘Oh, yes. The wonderful yoghurt. It’s the only thing I miss.’

‘Enjoy it,’ I said, and wished them both good luck in New York. On the way out, I murmured to Rosario: ‘And don’t visit any opticians.’

After leaving, I was struck by the fact that, throughout the dinner, I had not seen Daniel Ortega actually eat anything. I had been right next to him, and he had turned away all the evening’s delicacies, even the turtle meat. (Which had been unexpectedly dense and rich, like a cross between beef and venison. The turtles, incidentally, were protected during the whole of their breeding season, and could only be caught in limited quantities for a few months of the year.)

I found out that he was known for this little habit, which could have been a sign of nervousness, or, more likely, an attempt to make himself seem a man apart, different from the crowd.

And perhaps, when nobody was looking,

el señor Presidente

would sneak into his kitchens and stuff himself in secret.

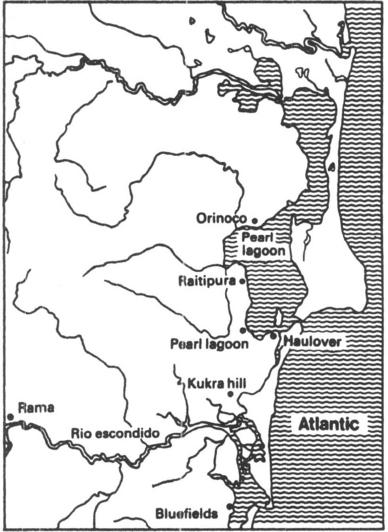

Map of Bluefields

12

THE OTHER SIDE

Rub me belly skin (O mama)

Rub me belly skin (O baby)

Rub me belly skin

With castor oil …

T

he music of Rundown, a local group, played at top volume on a ghetto blaster, welcomed me to Bluefields, on Nicaragua’s Atlantic coast.

Costeña

music, Nicaragua’s answer to calypso, reggae and ska, had been one of the main reasons why I’d become so determined to get over to Nicaragua’s other side. I had also formed an ambition to swim in the Caribbean – because the Atlantic coast was, of course, really the Caribbean coast, as the locals were quick to point out – and the Pacific on the same trip. I’d already had my swim in the Pacific, strolling into the warm, warm water at Pochomil beach near Managua, where once the Somoza gang would take its weekend dips; now for the

Mar Caribe

.

In Bluefields it was often difficult to remember I was still in Nicaragua. The west coast was, for the most part, racially homogeneous, but here, as well as

mestizos

, there were Creoles, three different Amerindian tribes, and even a small community of Garifonos who shouldn’t have been there at all, according to the textbooks, but up in Belize. And that wasn’t the only difference. The majority of the inhabitants here were not Catholic, but belonged to the Moravian church. And a large proportion of them were English-speaking, to boot.

The culture of Bluefields felt distinctly West Indian, but it was more or less totally cut off from contact with the rest of the Caribbean – excepting Cuba. It wasn’t very closely in touch with the Pacific coast of Nicaragua itself, come to that. In Bluefields you couldn’t receive Nicaragua’s ‘Sandinista Television’, so you watched the Costa Rican programmes instead. It could take you all day to get a phone connection to Managua, and even then you might not manage it. There was no road link between the coasts. The few air flights filled up weeks in advance, and the only other route involved travelling 100 kilometres on a slow ferry down the Río Escondido (the ‘Hidden River’ that used to shelter pirate ships in the Days of Yore) as far as the township of Rama, where the 300-kilometre road from Managua came to an abrupt halt. The ferries had been frequent targets for the Contra. About a month before my visit they had burned the penultimate boat. The banks of the river were thickly jungled, and the ferries were sitting ducks; but the people, having no option, continued to use the route.

What would happen when the Contra burned the last boat? The only answer I ever got to this question was a fatalistic shrug. To live in Bluefields was to accept remoteness, just as it was also to accept rain. It was one of the wettest places I had ever been in. ‘May is sunny,’ people said, but that was cold comfort in July.

Apart from music and swimming, I was taken to Bluefields by a desire to find out if the revolution still felt, over there, like a new sort of conqueror. The inhabitants of the vast Atlantic coast province of Zelaya (only about 200,000 of them in almost half the country’s land area, almost all of it covered with virgin jungle and criss-crossed by inland waterways) had not had much to do with the making of the revolution. As a matter of fact, throughout the country’s history, the two coasts had not had much to do with one another at all. The Pacific coast had been a Spanish colony, but even though Columbus had landed in 1502 on the spot where Bluefields now stood, it had been the British who established, in 1625, the Protectorate of Mesquitía. Their subjects were mainly Amerindians: the Mosquitos or Miskitos, the Sumos and the Ramas. The British set up a puppet Miskito ‘kingdom’. These Miskito ‘monarchs’, often educated in the British West Indies or even in Britain, were based in the village of Pearl Lagoon to the north of present-day Bluefields. The Miskitos repressed the Sumos and Ramas so thoroughly that, today, barely a thousand Ramas (and not many more Sumos) were still alive. When I heard this, I realized that my mental picture of the Miskitos as a ‘pure’ tribal people whose ancient way of life had been disrupted by the Sandinistas, might need a little revision.