The Information (9 page)

(The Uncertainty in Our Writing, the Inconstancy in Our Letters)

In such busie, and active times, there arise more new thoughts of men, which must be signifi’d, and varied by new expressions.

—Thomas Sprat (1667)

♦

A VILLAGE SCHOOLMASTER AND PRIEST

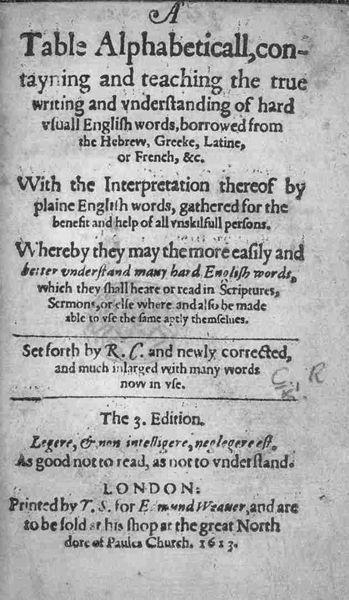

made a book in 1604 with a rambling title that began “A Table Alphabeticall, conteyning and teaching the true writing, and understanding of hard usuall English wordes,” and went on with more hints to its purpose, which was unusual and needed explanation:

♦

With the interpretation thereof by plaine English words, gathered for the benefit & helpe of Ladies, Gentlewomen, or any other unskilfull persons.

Whereby they may the more easily and better understand many hard English wordes, which they shall heare or read in Scriptures, Sermons, or elsewhere, and also be made able to use the same aptly themselves.

The title page omitted the name of the author, Robert Cawdrey, but included a motto from Latin—“As good not read, as not to understand”—and situated the publisher with as much formality and exactness as could be expected in a time when the

address

, as a specification of place, did not yet exist:

At London, Printed by I. R. for Edmund Weaver, & are to be sold at his shop at the great North doore of Paules Church.

CAWDREY’S TITLE PAGE

Even in London’s densely packed streets, shops and homes were seldom to be found by number. The alphabet, however, had a definite order—the first and second letters providing its very name—and that order had been maintained since the early Phoenician times, through all the borrowing and evolution that followed.

Cawdrey lived in a time of information poverty. He would not have thought so, even had he possessed the concept. On the contrary, he would have considered himself to be in the midst of an information explosion, which he himself was trying to abet and organize. But four centuries later, his own life is shrouded in the obscurity of missing knowledge.

His

Table Alphabeticall

appears as a milestone in the history of information, yet of its entire first edition, just one worn copy survived into the future. When and where he was born remain unknown—probably in the late 1530s; probably in the Midlands. Parish registers notwithstanding, people’s lives were almost wholly undocumented. No one has even a definitive spelling for Cawdrey’s name (Cowdrey, Cawdry). But then, no one agreed on the spelling of most names: they were spoken, seldom written.

In fact, few had any concept of “spelling”—the idea that each word, when written, should take a particular predetermined form of letters. The word

cony

(rabbit) appeared variously as

conny, conye, conie, connie, coni, cuny, cunny

, and

cunnie

in a single 1591 pamphlet.

♦

Others spelled it differently. And for that matter Cawdrey himself, on the title page of his book for “teaching the true writing,” wrote

wordes

in one sentence and

words

in the next. Language did not function as a storehouse of words, from which users could summon the correct items, preformed. On the contrary, words were fugitive, on the fly, expected to vanish again thereafter. When spoken, they were not available to be compared with, or measured against, other instantiations of themselves. Every time people dipped quill in ink to form a word on paper they made a fresh choice of whatever letters seemed to suit the task. But this was changing. The availability—the solidity—of the printed book inspired a sense that the written word

should be

a certain way, that one form was right and others wrong. First this sense was unconscious; then it began to rise toward general awareness. Printers themselves made it their business.

To spell

(from an old Germanic word) first meant to speak or to utter. Then it meant to read, slowly, letter by letter. Then, by extension, just around Cawdrey’s time, it meant to write words letter by letter. The last was a somewhat poetic usage. “Spell Eva back and Ave shall you find,” wrote the Jesuit poet Robert Southwell (shortly before being hanged and quartered in 1595). When certain educators did begin to consider the idea of spelling, they would say “right writing”—or, to borrow from

Greek, “

orthography

.” Few bothered, but one who did was a school headmaster in London, Richard Mulcaster. He assembled a primer, titled “The first part [a second part was not to be] of the Elementarie which entreateth chefelie of the right writing of our English tung.” He published it in 1582 (“at London by Thomas Vautroullier dwelling in the blak-friers by Lud-gate”), including his own list of about eight thousand words and a plea for the idea of a dictionary:

It were a thing verie praiseworthie in my opinion, and no lesse profitable than praise worthie, if some one well learned and as laborious a man, wold gather all the words which we use in our English tung … into one dictionarie, and besides the right writing, which is incident to the Alphabete, wold open unto us therein, both their naturall force, and their proper use.

♦

He recognized another motivating factor: the quickening pace of commerce and transportation made other languages a palpable presence, forcing an awareness of the English language as just one among many. “Forenners and strangers do wonder at us,” Mulcaster wrote, “both for the uncertaintie in our writing, and the inconstancie in our letters.” Language was no longer invisible like the air.

Barely 5 million people on earth spoke English (a rough estimate; no one tried to count the population of England, Scotland, or Ireland until 1801). Barely a million of those could write. Of all the world’s languages English was already the most checkered, the most mottled, the most polygenetic. Its history showed continual corruption and enrichment from without. Its oldest core words, the words that felt most basic, came from the language spoken by the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, Germanic tribes that crossed the North Sea into England in the fifth century, pushing aside the Celtic inhabitants. Not much of Celtic penetrated the Anglo-Saxon speech, but Viking invaders brought more words from Norse and Danish:

egg, sky, anger, give, get

. Latin came by way of Christian

missionaries; they wrote in the alphabet of the Romans, which replaced the runic scripts that spread in central and northern Europe early in the first millennium. Then came the influence of French.

Influence

, to Robert Cawdrey, meant “a flowing in.” The Norman Conquest was more like a deluge, linguistically. English peasants of the lower classes continued to breed

cows

,

pigs

, and

oxen

(Germanic words), but in the second millennium the upper classes dined on

beef

,

pork

, and

mutton

(French). By medieval times French and Latin roots accounted for more than half of the common vocabulary. More alien words came when intellectuals began consciously to borrow from Latin and Greek to express concepts the language had not before needed. Cawdrey found this habit irritating. “Some men seek so far for outlandish English, that they forget altogether their mothers language, so that if some of their mothers were alive, they were not able to tell, or understand what they say,”

♦

he complained. “One might well charge them, for counterfeyting the Kings English.”

Four hundred years after Cawdrey published his book of words, John Simpson retraced Cawdrey’s path. Simpson was in certain respects his natural heir: the editor of a grander book of words, the

Oxford English Dictionary

. Simpson, a pale, soft-spoken man, saw Cawdrey as obstinate, uncompromising, and even pugnacious. The schoolteacher was ordained a deacon and then a priest of the Church of England in a restless time, when Puritanism was on the rise. Nonconformity led him into trouble. He seems to have been guilty of “not Conforming himself” to some of the sacraments, such as “the Cross in Baptism, and the Ring in Marriage.”

♦

As a village priest he did not care to bow down to bishops and archbishops. He preached a form of equality unwelcome to church authorities. “There was preferred secretly an Information against him for speaking diverse Words in the Pulpit, tending to the depraving of the Book of Common Prayer.… And so being judged a dangerous Person, if he should continue preaching, but infecting the People with Principles different from the Religion established.” Cawdrey was degraded from

the priesthood and deprived of his benefice. He continued to fight the case for years, to no avail.

All that time, he collected words (“

collect

, gather”). He published two instructional treatises, one on catechism (“

catechiser

, that teacheth the principles of Christian religion”) and one on

A godlie forme of householde government for the ordering of private families

, and in 1604 he produced a different sort of book: nothing more than a list of words, with brief definitions.

Why? Simpson says, “We have already seen that he was committed to simplicity in language, and that he was strong-minded to the point of obstinacy.” He was still preaching—now, to preachers. “Such as by their place and calling (but especially Preachers) as have occasion to speak publiquely before the ignorant people,” Cawdrey declared in his introductory note, “are to bee admonished.” He admonishes them. “Never affect any strange ynckhorne termes.” (An

inkhorn

was an inkpot; by

inkhorn term

he meant a bookish word.) “Labour to speake so as is commonly received, and so as the most ignorant may well understand them.” And above all do not affect to speak like a foreigner:

Some far journied gentlemen, at their returne home, like as they love to go in forraine apparrell, so they will pouder their talke with over-sea language. He that commeth lately out of France, will talk French English, and never blush at the matter.

Cawdrey had no idea of listing

all

the words—whatever that would mean. By 1604 William Shakespeare had written most of his plays, employing a vocabulary of nearly 30,000, but these words were not available to Cawdrey or anyone else. Cawdrey did not bother with the most common words, nor the most inkhorn and Frenchified words; he listed only the “hard usual” words, words difficult enough to need some explanation but still “proper unto the tongue wherein we speake” and “plaine for all men to perceive.” He compiled 2,500. He knew that many were derived

from Greek, French, and Latin (“

derive

, fetch from”), and he marked these accordingly. The book Cawdrey made was the first English dictionary. The word

dictionary

was not in it.

Although Cawdrey cited no authorities, he had relied on some. He copied the remarks about inkhorn terms and the far-journeyed gentlemen in their foreign apparel from Thomas Wilson’s successful book

The Arte of Rhetorique

.

♦

For the words themselves he found several sources (“

source

, wave, or issuing foorth of water”). He found about half his words in a primer for teaching reading, called

The English Schoole-maister

, by Edmund Coote, first published in 1596 and widely reprinted thereafter. Coote claimed that a schoolmaster could teach a hundred students more quickly with his text than forty without it. He found it worthwhile to explain the benefits of teaching people to read: “So more knowledge will be brought into this Land, and moe bookes bought, than otherwise would have been.”

♦

Coote included a long glossary, which Cawdrey plundered.

That Cawdrey should arrange his words in alphabetical order, to make his

Table Alphabeticall

, was not self-evident. He knew he could not count on even his educated readers to be versed in alphabetical order, so he tried to produce a small how-to manual. He struggled with this: whether to describe the ordering in logical, schematic terms or in terms of a step-by-step procedure, an algorithm. “Gentle reader,” he wrote—again adapting freely from Coote—

thou must learne the Alphabet, to wit, the order of the Letters as they stand, perfectly without booke, and where every Letter standeth: as

b

neere the beginning,

n

about the middest, and

t

toward the end. Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with

a

then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with

v

looke towards the end. Againe, if thy word beginne with

ca

looke in the beginning of the letter

c

but if with

cu

then looke toward the end of that letter. And so of all the rest. &c.