The Indian Clerk (8 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

He is just arriving at the Trinity gates when Norton catches up with him. "Hello, Hardy," he says—and the Indian wraith evaporates.

"Heading home?" Hardy asks.

Norton nods. "I've been walking. The meeting left me full of agitated energy. I couldn't go to bed . . . I mean, I couldn't

go to sleep yet."

He winks. He is not good-looking. More and more, the older he gets, does he resemble a monkey. Still, Hardy smiles at the

invitation.

"You might come up for a cup of tea," he says, ringing the bell. Norton nods assent. Then they are quiet, lost in a silence

in which there lingers an embarrassed silt of compromise, of settling for what's available in the absence of what's desired.

Footfalls sound in the gloom, an impish, spiteful Cupid beats a drum, and Chatterjee—the real Chatterjee, decked out in his

Corpus Christi robes—comes marching down Trinity Street, his heels beating out a rhythmic tap against the pavement. As he

nears, his features merge into focus: ski-slope nose, lips turned up in a subtle smile, eyebrows that nearly join, but not

quite. He passes so close that Hardy can feel the rushing of his robes, breathe in their smell of wardrobes. Then he's gone.

He doesn't even meet Hardy's eye. The fact is, Chatterjee has no idea who he is.

It is at this instant that the porter arrives. Thinking them two undergraduates out after hours, he starts to give them a

tongue-lashing—until he recognizes Hardy. "Good evening, sir," he says, holding the gate open, his face a bit red, if truth

be told. "A pleasant night out?"

"Pleasant enough, thank you. Goodnight."

"Goodnight, sir. Goodnight, Mr. Norton."

"Goodnight."

Great Court is empty at this hour, vast as a ballroom, the lawn gleaming in the moonlight. Sometimes Hardy thinks of his Cambridge

life as being divided into quadrants, much like the lawn of Great Court. One quadrant is mathematics, and Littlewood, and

Bohr. The second is the Apostles. The third is cricket. The fourth . . . In truth, this is the quadrant he is most reluctant

to define, not from squeamishness—on the contrary, he has little patience for the attempts that Moore and others make to dress

the matter up in philosophical vestments—but because he doesn't know what words to use. When McTaggart speaks of the higher

sodomy, he tries to draw a veil over the physical, about which Hardy feels no shame. No, the bother is when the quadrants

touch—as they are touching now, Norton at his side, the two of them heading toward New Court surreptitiously even though there

is nothing outwardly suspect in his inviting a friend to his room for a cup of tea that he knows will never be brewed.

They climb the stairs and he opens the door. Rising from Gaye's blue ottoman, Hermione arches her back, raises her tail in

greeting. "Hello, puss," Norton says, bending over to stroke Hermione, as Hardy presses his fingers against his neck, trying

to remember the last time he stroked human skin, and not a cat's fur. He tries to remember, and he can't.

W

HEN LITTLEWOOD disappears from Cambridge, which he frequently does, it is usually to go down to Treen, in Cornwall, where

he stays with the Chase family,

or, more precisely, with Mrs. Chase and her children. Their father—Bertie Russell's doctor—lives in London, coming down to

Treen once a month or so. About the understandings Littlewood has come to with Mrs. Chase, or Dr. Chase, or both, Hardy knows

better than to enquire. Certainly such arrangements are not unheard of: Russell himself appears to have arrived at one with

Philip Morrell, with whose wife, Ottoline, he is having an affair he can never quite keep secret. Indeed, the only sufferer

in that situation appears to be Russell's own wife.

Littlewood has no wife. Both of them are fated to die bachelors, Hardy suspects: Littlewood because Mrs. Chase will never

leave her husband, Hardy for rather more obvious reasons. This, he thinks, is why they can work with each other so much more

easily than either can work, say, with Bohr, who is married. It isn't only a question of the occasional, unannounced, late-night

visit; they also know when to leave each other alone. The married, he has noticed, are forever trying to persuade Hardy to

join their fellowship. They live to advertise that brand of conjugal domesticity to which they have pledged themselves. It

wouldn't be possible to collaborate with a married man, because a married man would always be noticing—questioning—that Hardy

himself isn't married.

Littlewood never questions Hardy. Nor does he mention Gaye. He is a man who has little patience with those rules that delimit

what one is and isn't supposed to talk about. Even so, he has to admit that he's just as glad that Hardy prefers not to share

with him what Mrs. Chase calls "the gory details." Much easier, if not to defend, than at least to explain Hardy as an abstraction,

especially when Jackson—the wheezy old classicist whose inexplicable fondness for him Littlewood feels as a sort of rash or

eczema—puts his mouth to his ear at high table and whispers, "How can you stand working with him? A normal fellow like you."

Littlewood has a canned answer to this kind of inquiry, which he gets often. "All individuals are unique," he says, "but some

are uniquer than others." He'll only go further if the inquirer is someone he trusts, someone like Bohr, to whom he describes

Hardy as a "nonpracticing homosexual." Which, so far as he can ascertain, is perfectly accurate. Aside from Gaye—whose relationship

with Hardy Littlewood could not begin to parse—Hardy, from what he can tell, has never had a lover of either sex; only periodic

episodes of besottedness with young men, some of them his students.

Mrs. Chase—Anne—thinks Hardy tragic. "What a sad life he must lead," she said to Littlewood this past weekend in Treen. "A

life without love." And though he agreed, privately Littlewood couldn't help but reflect that such a life must not be without

its advantages—he, a man who often finds himself contending with a surfeit of love: Anne's, and her children's, and his parents',

and his siblings'. There are moments when all this love chokes him, and during these moments he regards Hardy's solitude as

an enviable alternative to the overpopulated lives for which his married friends have volunteered; the abundance of wives,

children, grandchildren, sons- and daughters-in-law, mothers- and fathers-in-law; the murk of demands, needs, interruptions,

recriminations. Whenever he goes to visit these friends in the country, or has supper with them at their Cambridge houses,

he returns to his rooms full of gratitude, that he can climb into his bed alone and wake up alone—but knowing that, come the

next weekend, he will not be alone. Perhaps this is why the arrangement with Anne suits him so well. It is a thing of weekends.

The first Friday in March, as is his habit, he goes to Treen. Rain keeps him indoors most of Saturday and Sunday. On Monday

it's still raining; at the station, he learns that somewhere along the line a bridge has flooded, diverting his train, which

arrives two hours late. This leaves him stuck at Liverpool Street for two hours. By the time he gets back to Cambridge, it's

too late for dinner, still raining, and he's been traveling all day. He curses, throws his bags down on his bedroom floor,

picks up his umbrella, and heads over to the Senior Combination room. Shadowed figures lurk in the paneled gloaming. Jackson,

greeting him with a nod, points with his drink to a corner of the room where, much to his surprise, he glimpses Hardy sitting

upright in a Queen Anne chair, hands on his knees. At the sight of him, Hardy bolts up and hurries toward him.

"Where were you?" he asks in a hiss.

"The country. My train was delayed. What's the matter?"

"It's come."

Littlewood stops in his tracks. "When?"

"This morning. I've been looking for you all day."

"I'm sorry. Look, what does it say?"

Hardy glances toward the fire. A small group of dons has clustered there to smoke. Until Littlewood walked in, they were talking

about Home Rule in Ireland. Now they're silent, ears cocked.

"Let's go to my rooms," Hardy says.

"Fine, if you'll give me a drink," Littlewood says. And they turn around and leave. The rain is coming down in sheets. Hardy

has forgotten his umbrella, and Littlewood must hold his over both of them. It makes for an uncomfortable intimacy, if one

that only lasts the minute or so that it takes to walk over to New Court. Opening the door to his staircase, Hardy pulls away,

clearly as relieved to be separated as Littlewood is. He shakes out his umbrella and drops it in the Chinese ceramic jar that

Littlewood remembers from the old days, when Hardy shared a suite with Gaye on Great Court.

"I've only got whiskey," Hardy says, leading him up the stairs.

"That will do splendidly." Hardy opens the door to his suite.

"Hello, cat," Littlewood says to Hermione, but when he bends down to pat her head, she runs away.

"What's the matter with her? I was only trying to be friendly."

"You treat her as if she's a dog." Hardy pulls the letter from his pocket. "Well, at least one thing's as I suspected," he

says. "I'm not the first he's written to."

"No?"

"Oh, do take off your coat. Sit down. I'll get the whiskey."

Littlewood sits. Hardy pours the whiskey into two somewhat dirty glasses, hands one to Littlewood, then reads aloud.

" 'Dear Sir, I am very much gratified on perusing your letter of the 8th February 1913.1 was expecting a reply from you similar

to the one which a Mathematics Professor at London wrote asking me to study carefully Bromwich's Infinite Series and not fall

into the pitfalls of divergent series.' That's Hill, I expect. Anyway: ‘I have found a friend in you who views my labours sympathetically.

This is already some encouragement to me to proceed with my onward course.'"

"Good."

"Yes, but now comes the worrisome part. I find in many a place in your letter rigorous proofs are required and so on and you

ask me to communicate the methods of proof. If I had given you my methods of proof, I am sure you will follow the London Professor.

But as a fact, I did not give him any proof but made some assertions as the following under my new theory. I told him that

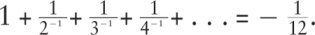

the sum of an infinite number of terms of the series: 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + . . . = -1/12 under my theory.'"

"Yes, that was in the last one, too."

"If I tell you this you will at once point out to me the lunatic asylum as my goal. I dilate on this simply to convince you

that you will not be able to follow my methods of proof if I indicate the lines on which I proceed in a single letter.'"

"He's hedging. Maybe he's afraid you'll try to steal his stuff."

"That's what I thought, too. But then there's this: 'So

what I now want at this stage is for eminent professors like you to recognize that there is some worth in me. I am already

a half-starving man. To preserve my brains I want food and this is now my first consideration.'"

"Do you think he's actually starving?" Littlewood asks.

"Who knows? What does twenty pounds a year buy in Madras? And here's how it ends: 'You may judge me hard that I am silent

on the methods of proof. I have to reiterate that I may be misunderstood if I give in a short compass the lines on which I

proceed. It is not on account of my unwillingness on my part but because I fear I shall not be able to explain everything

in a letter. I do not mean that the methods should be buried with me. I shall have them published if my results are recognized

by eminent men like you.' And then there are—what?—ten pages of mathematics."

"And?"

"Well, at least I've worked out what he's up to with the damn 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = -1/12."

"What?"

"I'll show you." With a quick sweep of the cloth, Hardy wipes his blackboard clean. "Essentially, it's a matter of notation.

His is very peculiar. Let's say you decide you want to write 1/2 as 2

-1

. Perfectly valid, if a little obscurist. Well, what he's doing here is writing 1/2

-1

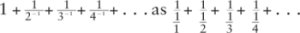

as 1/1/2, or 2. And then, along the same lines, he writes the sequence , which is of course 1+2+3+ 4 + . . . So what he's really saying is

, which is of course 1+2+3+ 4 + . . . So what he's really saying is "

"

"Which is the Riemannian calculation for the zeta function fed with - 1."

Hardy nods. "Only I don't think he even knows it's the zeta function. I think he came up with it on his own."

"But that's astounding. I wonder how he'll feel once he finds out Riemann did it first."

"My hunch is that he's never heard of Riemann. Out in India, how could he? They're behind England, and look how far England

is behind Germany. And of course, since he's self-taught, it makes sense that his notation would be a little—well—off."

"True, except that he seems to

know

it's off. Otherwise why put in the bit about the lunatic asylum?"

"He's toying with us. He thinks he's great."

"Most great men do."

A silence falls. Gulping his whiskey, Littlewood regards Hermione. Her gaze—predatory and accusatory and bored—disconcerts

him. The fact is, he's no more comfortable here, in Hardy's territory, than Hardy is in his. The cat makes him nervous, as

do the bits of decorative frippery, the ottoman with its hairy fringe and the bust on the mantelpiece. Gaye, it appears.

Putting down his glass, he takes the letter from where Hardy's dropped it; stands up. "Do you mind if I follow tradition and

borrow this?" he asks.

"Be my guest. Likely you'll have more luck than I have."

"I don't see why."

"You're the one who was senior wrangler."

Littlewood raises his eyebrows.

What brought that on?

"Show it to Mercer then," he says, handing the letter back—a little surprised by his own vehemence.

Hardy looks as if he's just been slapped. But Littlewood has already turned away from him, to Hermione. "Goodbye, cat," he

says.

She ignores him.

"Sometimes I think she's deaf."

"She is deaf."

"What?"

"A recessive gene. Most white cats are deaf."

"Oh, of course," Littlewood says. "Of course you'd have a deaf cat. I should have guessed."

He moves toward the door, and Hardy reaches out his hand to stop him. "I'm sorry," he says. "I didn't mean to offend, or .

. . Look, just take the letter."

"I'm not offended. Just perplexed. That you should bring up a thing like that. Is it really such a sore spot? Still?"

"Of course not. I just—"

"And you can't think it matters to

me.

I hate the damn thing as much as you do."

"I know. I misspoke. A poor effort at a joke. Please, take the letter."

He holds it out like an offering. Reluctantly Littlewood accepts it. Hardy looks humbled, and Littlewood's umbrage melts.

Poor fellow! "Very good, sir," he says, to show there are no hard feelings, and mimics a military salute. "Goodnight."

"Goodnight," Hardy replies, his voice chilly and wistful. He shuts the door.

Littlewood is still young enough that, when he's alone and going downstairs, he bounds, taking the steps two at a time. Right

now he's thinking about Mercer—not Mercer as he is today, but as he was when they were both coaching for the tripos. Back

then, Mercer only spoke when spoken to. When he was writing, his head bobbed over the paper with metronomic regularity. Littlewood

will be the first to admit that Mercer's strange mode of concentration, his apparent obliviousness to everything around him,

unnerved him in a way that the stunts perpetrated by his more competitive fellows—gestures

meant

to distract—never did. And what in Mercer could possibly have appealed to Hardy? Not that he wants to hear the gory details

of the case, which in this instance probably aren't even details of sex, but rather of infatuation, which is somehow worse.

Littlewood knows, because he's been on the receiving end of infatuation: the hours the poor devils spend trying to "read"

a smile, or interpret a pat on the shoulder, or discern the secret import of the loan of a pencil. Schoolgirl nonsense. And

the notes: "Although we have never spoken, and I am no doubt invisible to you, may I risk offense by remarking on the pleasure

I have taken, so many mornings, watching you bathe . . ." Still, he'd be curious to hear how things started with Mercer, and

why they soured.