The Indian Clerk (18 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

"You see, Ramanujan," Neville says, "we English are basically cavemen. Given our druthers, we'd tear raw meat off the bone

with our teeth, and so when we eat vegetarian food, we try to create simulacra of the sorts of things we crave. Vegetable

goose, vegetable sausage, vegetable steak-and-kidney pie."

Appalled silence greets this menu. "What? Do you think I'm joking? I've had a look at Alice's cookbook, and all these are

bona fide recipes."

Ramanujan is blushing. A little smile has crept onto his face. Neville is chaffing him, Hardy sees, and he is enjoying it.

"Call the dish what you will," Mrs. Neville says, slicing into the lump. "All that it is is a vegetable marrow stuffed with

bread, sage, and apples and then baked."

Steam escapes from the first incision, carrying with it a strong whiff of cinnamon. A first slice is produced, plated, and

put before Ramanujan.

"There's just one thing I don't understand," Littlewood says, as the rest of the plates are handed round. "Why on earth would

a vegetarian want to eat imitation meat? I thought the whole point was . . . well. . .

not

to eat meat. To eat vegetables."

"Personally, I'd rather have this than a plate of cold boiled turnips," Neville says, tucking in. "Delicious, darling."

"Thank you, Eric. And what do you think, Mr. Ramanujan?"

"Very tasty, Madam," Ramanujan says—still ill at ease, Hardy can see, with the fork. Primitive implement, designed to pierce

flesh. Poor fellow. He must not be used to such flavors. Hardy himself is not used to such flavors. For him, the cloying sweetness

of the cinnamon only makes the mush of marrow more repulsive.

The meal concludes with sago pudding, after which the party returns to the sitting room for coffee—which, Hardy is pleased

to note, Ramanujan accepts with great enthusiasm. As Mrs. Neville proceeds to explain in her Baedeker voice, coffee is very

popular in Madras, even more popular than tea, though it's prepared in a different way: boiled with the milk and then sweetened.

They drain their cups, and with exaggerated apologies—perhaps this has been pre-arranged with Neville—she explains that she

has some "household matters to attend to" and leaves the room. Now, Hardy supposes, they are supposed to talk mathematics.

Good God, how awful! Even worse than the small talk! He wants to escape, and wonders if Ramanujan must feel the same way.

But then Neville asks Ramanujan a question about the zeta function, on which Ramanujan proceeds to expatiate, at first haltingly,

then with growing confidence. It seems that he has been shown Hardy's proof—just now published—that there are an infinite

number of zeros along the critical line.

Only now does Hardy have the presence of mind to really

see

him. The heavy-lidded eyes, dark and searching, glance out from beneath a massive, furrowed brow. The hair, though short,

is thick and luxuriant. Perhaps because Mrs. Neville is no longer present, he has unbuttoned his jacket, with the result that

he looks altogether more comfortable. He says that he's becoming interested in what he calls "highly composite numbers." Littlewood

asks what he means. "I suppose I mean," Ramanujan says, "a number that is as far from a prime as a number can be. A sort of

anti-prime."

"Fascinating," Littlewood says. "Could you give us an example?"

"24."

Hardy raises his eyebrows.

"None of the numbers up to 24 has more than

6

divisors. 22 has 4, 21 has 4, 20 has 6. But 24 has 8. 24 can be divided by 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, or 24. So I define a 'highly

composite number' as a number that has more divisors than any number that comes before it."

What a strange mind! What a strange, ranging mind!

"And how many of these numbers have you calculated?"

"I have listed every highly composite number up to 6,746,328,388,800."

"And have you drawn any conclusions about these numbers?" Neville asks.

"Well, yes. You see, you can work out a formula for a highly composite

N

—" He makes a grasping motion with his fingers, as if reaching for an invisible pencil, at which Neville stands and says,

"Hold on a minute." Then he goes out of the room and returns, a few seconds later, bearing a blackboard on legs and some chalk.

Awkwardly Ramanujan stands beside the blackboard. "Well," he says, "if we say

N

is a highly composite number, then the following formula can be written for N."

And he's off. At the blackboard, any self-consciousness he might feel about speaking English leaves him, just as Hardy's discomfort

evaporates. They're lost now, and when, an hour later, Alice Neville peers down from the top of the stairs, she sees four

men she hardly recognizes, speaking a language she cannot hope to understand.

A

LICE STROLLS DOWN the corridor and steps into the spare room, the door of which Ramanujan has left ajar. His trunk—dark leather,

barely scuffed—sits neatly packed on the floor. The surface of the bureau is empty, the washbasin clean. The bed appears not

to have been slept in. How is this possible? She feels under the blankets, and realizes that the sheets haven't been touched.

So has he slept on the floor? Or perhaps on top of the candlewick bedspread, the beige surface of which he smoothed upon waking?

No unfamiliar odor has penetrated the room, as if, in his modesty, Ramanujan has held back even the exhalations of his body.

She smells only the clean scent of the scrubbed wood floor and the cold spring air.

Earlier in the week, when she was preparing this room for Ramanujan, she found herself wondering what he would make of the

stiff, high bed, the varnished bureau, the walls unadorned except for a few Benozzo Gozzoli reproductions, picked up on their

honeymoon trip to Italy. Back in Madras, she knows, Ramanujan had no bed. Like most Indians, he and the other members of his

family slept on mattress rolls that could be folded up and put away during the day. Any spare piece of floor would serve as

a bedroom. And now here he is in England, where the trees are just coming into bud and, in order to sleep, he must climb up

onto a bed. What must he make of it all? Does the strangeness terrify him? Will he curl into himself? Hide from it? Or will

he find, in this strange, high bed, that a new Ramanujan—a version of himself that can only be born abroad, as some new version

of Alice was born in India—is, like the trees, just coming into bud?

She pushes the door to. Downstairs, the men's voices rise with excitement and impatience. No one is likely to interrupt her

as she opens the trunk, gazes at the neatly folded clothes and the notebooks lying atop them. In a toiletry kit—also new,

matching the trunk—she finds a hair brush, hair tonic, tooth powder, and a toothbrush. Feeling under the clothes, she fishes

out a book called

The Indian Gentleman's

Guide to English Etiquette,

a photograph of a young girl whom she assumes must be the wife, and a small, awkward brass object that, when she pulls it

free of its wadding of shirt, turns out to be a statue of Ganesha, the Hindu elephant god, god of success and education, of

new enterprises and auspicious starts, of literature. Ramanujan's Ganesha has a potbelly and wears a crown. In the first of

his four hands he holds a noose, in the second a goad, in the third a broken tusk to write with, and in the last a rosary.

His trunk curls around a sweet and to his right sits the rat that he rides as men ride horses.

Why doesn't Ramanujan take him out? Put him on the bureau next to the basin? Why doesn't he unpack his uncomfortable clothes,

and lay out his hairbrush and his tooth powder, and pull apart the bed so that he can lie between the sheets? She wishes she

could do these things for him. She knows that she dares not do these things for him. He likes her—that much is clear—but he

is too shy to show outward affection. And how can she force him to?

Very carefully, she returns the book and the statue of Ganesha back to the trunk, which she closes and clasps shut. Then she

sits on the bed, disrupting the perfect suavity of the spread. She thinks of the men downstairs, and for some reason, for

an instant, she feels as if she might die of loneliness.

Why does she care so much? Why does it matter to her, his being here in her house? Israfel wouldn't care.

She

would look forward to getting rid of him, getting him delivered to Trinity, after which she would clap her hands together

and say, "Well, thank goodness

that's

over." Only Alice is not Israfel, and so what she feels is grief.

Very gently she stands. She smoothes the wrinkles she has left in the bedspread—enough to create an effect of seemliness,

not enough so that Ramanujan will not know that someone has been sitting on his bed. Then she wanders back out into the corridor.

The sun is setting. The men keep talking. She should get them tea. She knows that. She should go downstairs, put some biscuits

on a plate, and get the water boiling. But she doesn't move.

R

AMANUJAN STAYS WITH the Nevilles for six weeks. There are regular dinners, to which a variety of Trinity luminaries are invited

so that they can lay eyes, at last, upon the "Hindoo calculator," as one of the newspapers has recently dubbed him. Russell

comes, as do Love, Barnes, Butler. One night Hardy is asked to bring Gertrude. By this point the horrid food at the Nevilles'

has become so much the stuff of gossip around Trinity that Hardy knows to dine Littlewood and his sister first, in his rooms,

so that when they are compelled to confront the latest aberration culled from Mrs. Neville's cookbook—vegetable trout, vegetable

shepherd's pie—they will be able to plead small appetites with impunity.

This night, though, a surprise awaits them. Rather than prepare some caricature of the flesh, Mrs. Neville announces that—thanks

to the recent arrival of certain spices ordered from London—she has prepared a vegetable curry. "In Mr. Ramanujan's homeland,

of course, we would eat with our fingers," she tells Gertrude. "But as I've explained to him, most English people are as uncomfortable

with this habit as he was, at first, with his fork. Now you've become quite the expert with our cutlery, haven't you, Mr.

Ramanujan?"

Ramanujan waggles his head. It took Hardy a while to get used to this curious gesture of his, a sort of hobbling from the

neck that, he has now come to understand, signifies a provisional yes. Make no mistake: Hardy feels nothing but gratitude

toward the Nevilles. They have cared for Ramanujan and made him feel at home, shown him how to navigate the byways of Cambridge

and the corridors of Trinity, fed him and bedded him and seem prepared to continue doing so for the duration of his stay.

That said, it rather annoys Hardy the degree to which they treat him, at least when others were present, as

theirs,

an intelligent pet ape in the process of being trained to act like a man. And look! Tonight, as a treat for the ape, we shall

dine on bananas! Well, perhaps that's too harsh. What's certain is that, in preparing a curry, Alice Neville is showing off

for Gertrude. For some reason it seems of paramount importance to Alice that she make a positive impression on Gertrude.

Hardy turns to glance at his sister. Her face registers no reaction whatsoever. There is no one in the world to whom he feels

closer than Gertrude, and yet, in certain fundamental ways, he cannot make sense of her. What does she think, for instance,

of the Nevilles' decor, which she takes in, as she takes in everything, coolly, without comment? Littlewood flirts with her

every time they meet. What can he see in her? She is bony and flat-chested and wears a brown sack of a dress, neither new

nor fashionable. So perhaps that's it—perhaps what attracts him is her absolute lack of self-consciousness. The same quality

drew Hardy to Littlewood once.

They sit down to eat. Rice is served from a ceramic bowl, the curry—which is soupy and yellowish, bobbing with bits of unidentifiable

vegetables—from a silver tureen. "Of course, Miss Hardy," Mrs. Neville says, "in Madras a curry of this sort would be far

more highly spiced. I've made certain modifications to suit the English stomach."

Indeed she has. If anything, the curry is blander than those versions of it that Hardy's mother, on occasion, prepared. That

said, it provides a welcome respite from vegetable goose. Indeed, he observes, Ramanujan himself is tucking into it with relish,

no doubt grateful even for this vague counterfeit of the food he is used to. And meanwhile Mrs. Neville natters on about Madras,

and the Indian way of eating—wrapping up the food in a sort of pancake—while Neville watches her, amused and serene. Ramanujan

says nothing; he only occasionally waggles his head. For it must be as clear to him as it is to Hardy that the performance

is really for Gertrude. Women are such unfathomable creatures, so conscious of one another as potential competitors, allies,

or prey! If you didn't know either of them, you might assume that Gertrude would be envious of Alice: Gertrude, the very embodiment

of the English spinster schoolteacher. And yet instead it is Alice who longs to win Gertrude's approbation. Why? Perhaps she

imagines that Gertrude is some paragon of cool wit and urbanity, the avatar of a world in which Alice, as it stands, would

feel hopelessly ill at ease. Nor does it matter that Gertrude is not that kind of woman at all, that in fact she would be

as intimidated by the Stephen sisters, or Ottoline Morrell, as Alice would. For Gertrude, to her credit, is good at games.

She knows that, once you're handed the ball, you run with it. And so, in Alice's presence, she plays the role that she has

been assigned. She is aloof and faintly condescending, ever refusing to bestow the kiss of approval for which Alice longs.

She withholds, and, in withholding, makes Alice curse herself for needing the love of a man even to know herself. Both women

watch Ramanujan closely. It's as if, for them, every facet of the Indian, even his genius, has an aroma as exotic and pungent

as the food Alice is describing. And does their gaze disconcert him, at least a little? He cannot be used to such attentions.

He is used to solitude.

Every morning, having been first breakfasted and dressed by Mrs. Neville to suit the weather conditions, he crosses the Cam,

walks across Midsummer Common, then takes King Street, Sussex Street, and Green Street to Trinity. Half an hour's walk, in

shoes that still blister his feet. For the rest of the morning, he and Hardy work together, usually just the two of them,

though sometimes Littlewood comes over. They work on Riemann. By now Hardy has established irrefutably that there is an infinity

of zeros along the critical line. But, as he told Miss Trotter, that does not mean that there is not, also, an infinity of

zeros

not

along the critical line. So really, Hardy has proven nothing; just made a step in the right direction.

The first job is to explain to Ramanujan why his own improvement on the prime number theorem is wrong. This turns out to be

something of a balancing act. On the one hand, Hardy needs to make him understand why his thinking was flawed, and, in particular,

to drive home the fact that accuracy to 1,000 integers, in mathematics, means nothing. On the other, he doesn't want to discourage

Ramanujan. He wants him to understand why his failure—and it is a failure—is in some ways more wonderful than any of his triumphs.

For the problem to which he dreamed his way in Kumbakonam is one that in Europe it took the finest mathematicians a century

just to articulate. And none of them—not Hadamard, not Landau, not Hardy—has solved it. Ramanujan may.

Unfortunately, he is impatient. He is itching to publish, he tells Hardy, so that he can show the men in Madras who encouraged

him that the time and money they spent was not wasted. And there is more to it than that, Hardy is sure. No human being, no

matter how spiritually evolved, is free of vanity. Even Ramanujan must dream of flaunting his success before those who failed

to value him, and, by doing so, making them feel as wretched as they made him feel. And not just the petty provincial bureaucrats

who took away his scholarships in Kumbakonam. The longing extends to Cambridge itself.

For instance, from early on—indeed, from the day he received Ramanujan's first letter—Hardy guessed that he was not the first

authority to whom Ramanujan had written. Now he asks, and receives verification that, well before he wrote to Hardy, Ramanujan

wrote to two of his Cambridge colleagues, Baker and Hobson. Neither took the trouble to reply.

The next morning Ramanujan wants to find out everything he can about Baker and Hobson. When and where do they lecture? If

he asks the porters at their colleges, can he find out where they live? Hardy tells him, though reluctantly. It's not that

he fears that Ramanujan would go so far as to confront these men, neither of whom he has met. He is far too shy. And yet Hardy

would not put it past him to slip newspaper announcements of his arrival in England under their doors.

Teaching him doesn't prove to be easy. The first two or three mornings Hardy spends trying to explain what a proof is, but

Ramanujan's attention keeps wandering. In many ways he is still the child making magic squares to amuse his school chums.

He won't focus, as Hardy would like him to, on Riemann; instead his mind moves in twenty directions at once, and though Hardy

tries to keep him on track, he dares not interrupt flights of associative fancy that might lead to unexpected discoveries.

One morning, for instance, they are talking about

n.

Hardy knows that during the lonely years he spent on his mother's

pial,

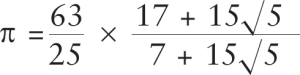

among the many formulae Ramanujan came up with were several intended to approximate the value of π.Some of these struck Hardy as quite remarkable, if for no other reason than because they were so peculiar; for instance:

Or:

Now Ramanujan is on to something more sophisticated. On his own, he has discovered that, by means of what are called modular

equations, it is possible to come up with new and incredibly rapid routes to

n:

series that converge with amazing speed, allowing the calculator, in a very short time, to write out the value of

n

to a very great distance. And where did he come up with these equations? To amuse himself, Hardy imagines him sleeping in

the Nevilles' guest room, imagines Namagiri—dark-skinned, in his mind's eye, with a Cleopatra fringe and painted cheeks and

thirty arms—patiently inscribing the formulae on his tongue. What a genius that goddess must be to be able to do what Moore

could not, to journey at her leisure into uncharted forests of the mind and return bearing jewels and treasure! There is a

path Hardy is beginning to discern, faint amid the foliage, leading from Ramanujan's flawed effort to improve on the Prime

Number theorem to the Riemann hypothesis and perhaps beyond. The question is, will his ambition help him or hinder him in

his navigation of that path? Or to put it another way: now that Ramanujan has crossed the ocean, will Namagiri follow?

So they pass their mornings, and then, in the afternoons, Ramanujan goes to lectures, or returns to the Nevilles' house, where

he does who knows what with Mrs. Neville until the sun sets, at which point there are those terrifying dinners, one or two

a week at least. What Mrs. Neville feeds Ramanujan when no guests are present Hardy dares not guess.

One night he proposes that he and Littlewood take Ramanujan to dinner at Hall. They pick him up at the Nevilles', walk away

with him as Mrs. Neville waves goodbye from the doorway, as forlorn as any mother sending her child off to school for the

first time. Neville meets them at Trinity, where a flurry of attention greets Ramanujan's arrival. For the first time he wears

his robe. Various men welcome him, and though it's not the usual thing—he isn't a fellow—he sits, on this occasion, between

Littlewood and Hardy at high table. Because the cook has been alerted to his vegetarianism, an unappetizing arrangement of

boiled potatoes, carrots, and turnips is placed before him, which he regards with suspicion. Who can blame him? Then again,

it's not for the food that he's come tonight.

Russell is across the table. He is avid to know Ramanujan's opinions—about Indian independence, about the suffrage movement,

about Home Rule in Ireland. To this interrogation Ramanujan appears unequal. His replies are flustered and hasty, especially

when suffrage comes up, as he doesn't even know the word. And how, after all, can he be expected to render an opinion on suffrage

when he comes from a country where most of the women cannot even read or write? It's not that Russell's baiting him, or teasing

him, it's just that he's off base. To Russell, Ramanujan is the very opposite of the exotic specimen that he is to Gertrude

and Alice: he's an emissary from another part of the world whose views Russell wants to solicit in the hope, no doubt, of

enlisting him in his own fledgling efforts to create a new England. Yet it's a useless effort, as Russell himself soon seems

to recognize, for he changes the subject. He asks about the work Ramanujan is doing.