The Illusion of Conscious Will (41 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

The idea that imagination becomes real is more difficult to apply to the case of unconscious channels. If the self is totally gone, submerged in a netherworld of mind and not even available to direct or execute the performance of the role-play, how could the pretending be done?

Who exactly

is doing the pretending? This question presupposes that there must always be a self, a subjective seat of consciousness, for the performance of a role or the creation of any virtual agent. But of course, this can’t be true. If there is always a self beneath any character we imagine and become, there should by extension also always be a self beneath the self. This suggests an infinite regress, a serious homunculus problem. To escape this conundrum, it is necessary to suppose that the person can perform actions without a self and that these can then be perceived as emanating from any virtual agent at all, including the self. In this view, the conscious will of a self is not necessary for creating voluntary action.

The transition from self to entity control that occurs in unconscious channelers seems to be a brief period when the person

assigns no author to action

. This transition appears quite unlike a normal waking state of consciousness and instead resembles sleep. It is useful to examine the phenomena of unconscious channeling of virtual agents in more depth, and it turns out much of the best descriptive evidence comes from studies of possession and trance states.

Possession and Trance

Many people have experienced spirit possession throughout history and around the world. To begin with, there is evidence for forms of possession and trance in the Hebrew and Greek roots of Western society. In 1 Samuel 10, for instance, God sent possessed prophets to Samuel who told him he too would be “overcome with the spirit of the Lord . . . and be turned into another man.” And in Greece the priestess Pythia at the Delphic oracle of Apollo went into trance to deliver her divinations. In medieval Europe, of course, there are many accounts of possession by devils, not to mention plenty of witchcraft (Bourguignon 1973; Oesterreich 1922). The stereotype of spirit possession in Western cultures stems largely from these archaic European examples viewed through the lens of a Christian account of possession. We can all bring to mind images of diabolical possession and exorcism from horror movies. But this is a stilted and unrepresentative stereotype.

10

In a sample of 488 societies, Bourguignon (1973) found that 90 percent exhibit institutionalized forms of altered states of consciousness, and 52 percent exhibit the specific case of trance with spirit possession. Most such possession occurs in religious contexts in which the spirit is benevolent and desirable, so the notion that such activity is satanic turns out worldwide to be a minority view (Lewis 1989).

The incidence of spirit possession has always been low in North America and Europe. Early groups such as the Shakers and the Quakers practiced forms of possession (by the Holy Spirit) as part of their worship (Garrett 1987), and there still exist significant minority religions (such as Pentecostal and Charismatic Catholic churches) that carry on such practices. But membership in such groups is small. The incidence of spirit possession is dramatically higher in certain societies of Africa, South America, and Asia. For example, spirit possession during trance is estimated to occur in 25 percent of the population of Malagasy speakers on the island of Mayotte off Southern Africa (Lambek 1988), in 50 percent of the !Kung bushmen of South Africa (Lee 1966), and in 47 percent of adult females among the Maasai of Tanzania, East Africa (Hurskainen 1989). Adherents of Vodoun (“voodoo”) in Haiti and of Santeria in Cuba include substantial proportions of the population, and the Afro-Brazilian religions Umbanda and Candomblé have upwards of 10 million adherents in Brazil (Brown 1986; Wafer 1991). In these religions, significant proportions of worshipers experience spirit possession as part of regular ceremonies. Any inclination we might have to write possession off as individual madness is seriously undermined by the sheer frequency of this phenomenon in some cultures. Seemingly, with the proper cultural support, almost anyone can become possessed.

10.

The stereotype of possession also usually suggests that people become possessed permanently or at least for lengthy bouts. Long-term possession is very rare, however, unlike possession trance, and is usually understood to be a form of mental disorder (Bourguignon 1976).

A typical example is the possession ritual in an Umbanda Pura ceremony in urban Brazil (described by Brown 1986). Meetings in the Umbanda church take place on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evenings at 8 o’clock. At first, the ceremony involves singing and hand-clapping that celebrates the Caboclo spirits (spirits of Amazonian Indians), and invites them to “come down and work.” The congregation moves around the small meeting hall in slow circle in a samba step. This may go on for half an hour or more, and then, “Mediums, as they become possessed, stop dancing, begin to perspire and often look slightly ill, sway, and then, bending over and giving a series of rapid jerks, receive their spirits. Upon straightening up, they have taken on the facial expressions, demeanor, and body motions characteristic of the particular spirit they have received. Caboclos wear stern, even fierce expressions and utter loud, piercing cries. They move vigorously around the dance floor in a kind of two-step, often dropping to one knee to draw an imaginary bow, and smoke large cigars, whose smoke will be blown over their clients as a form of ritual cleansing and curing” (Brown 1986, 81). Possessed mediums give

consultas,

consultations in which the members of the congregation seek the advice of the spirits for their problems. Ritual servants supply the Caboclos with fresh cigars and copy down recipes for herbal baths or other ritual preparations recommended to clients. These servants also help to interpret the advice of the spirits, which is often delivered in a ritual code language that is hard to understand. Later in the ceremony, possessions may occur by other classes of spirits, such as “old Blacks” (the wise and kindly spirits of slaves) or the spirits of children.

The behavior of the possessed has commonalities across cultures. The behavior depends, as in the Umbanda religion, on the particular spirit agent that is said to possess the host. There can be different classes of spirits possessing only certain people; in Northwest Madagascar, for instance, mass possession of school children during classes is blamed on “reckless and dangerous”

Njarinintsy

spirits, whereas older women experience possession by the more sedate

tromba

spirits (Sharp 1990). But, by and large, the possession involves a sequence much like that of trance channeling, in which the host may go limp or silent for a while or perhaps experience a period of convulsions or agitated movement. Brown (1986) notes in the Umbanda case that “in contrast to the extremely controlled possession states achieved by experienced mediums, possession, when it occurs among those inexperienced in controlling it, is often violent, and clients must be protected from injury to themselves or others” (83). When the spirit “gains control” of the host, some change in the host’s behavioral style typically signals the arrival of the new virtual agent (

fig. 7.4

). The possession may be fleeting or, in some cultures, may last many hours.

The induction of possession in the case of Umbanda also shares common features with induction in other cultures. Four such features are particularly worthy of note. They include a prior

belief

in the reality of the spirits, a socially sanctioned

ritual

in which one or more people are possessed in the presence of others, the use of a driving

rhythm

in the ritual, and the

interaction

of the spirit-possessed with other group members. Although different cultures add all sorts of twists to possession induction—some merely inducing trance without possession, others focusing on the induction in one person who is the spirit-master and healer of the group (in the practice of shamanism)—the characteristics of belief, ritual, rhythm, and interaction seem to be shared by many if not most spirit possession inductions (Boddy 1994; Goodman 1988; Lewis 1989; Locke and Kelly 1985; Price-Williams and Hughes 1994).

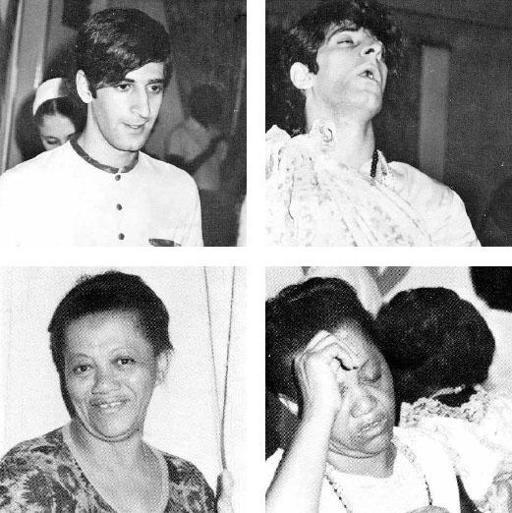

Figure 7.4

Before/after pictures of people being possessed by Coboclo spirits at an Umbanda ceremony. From Pressel (1973). Courtesy Esther Pressel.

The finding that people must have belief in the spirits comes as no surprise. We have already seen the importance of belief in action projection and the importance of transforming imagined agents into ones that are believed to be real for the creation of virtual agents. Belief in spirits is not just fanciful, but as emphasized by many anthropological commentators, it is strongly motivated. During possession, people suddenly have an ability to say and do things courtesy of the spirit that might otherwise be forbidden. Studying the Shango religion of Trinidad, Mischel and Mischel (1958) proposed that possession is widely learned because such release can be rewarding, allowing the expression of taboo impulses (“I spit on you and your cow”). Several anthropologists have suggested that this “alibi” theory might account for the finding that spirit possession occurs most often among people who are oppressed in their culture—usually, the women (Bourguignon 1976; Lewis 1989). The belief in spirits is not just the sharing of a fairy story, then, but instead is a useful fiction. Just as people might get drunk to excuse actions they are motivated to perform, they may urgently (yet perhaps unconsciously) want to believe in spirits to allow an avenue for the expression of thoughts and actions they might never be able to express otherwise.

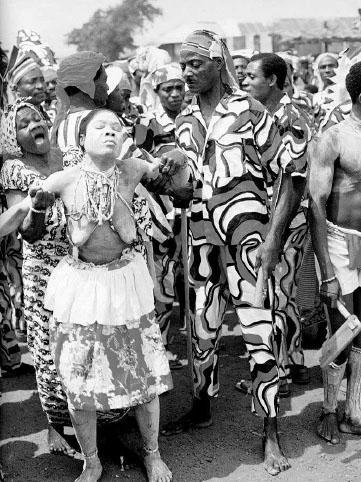

The form of the possession ritual is remarkably similar in many cultures. A group gathers, usually with some religious significance attached to their meeting and fully expecting that spirits will appear through some of those present. Dancing, singing, chanting, or listening to a speaker usually begin the ritual in a kind of group entrainment or co-action. This may last from a few minutes to many hours before the possessions begin, and then there may be simultaneous or sequential possessions in the group. The ritual may involve the use of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs and in different societies can include such features as preparatory rituals (e.g., fasting), special costumes (

fig. 7.5

), group rites of passage (e.g., marriage), and feats of bravery among the possessed or in preparation for possession (e.g., snake-handling, fire-walking).

Figure 7.5

A possessed priestess at an Akwambo festival in Ghana. From Cole and Ross (1977). Courtesy Herbert Cole.

Rhythm, in the form of music, drums, dancing, or chanting, is curiously customary in the production of trance. It is not absolutely essential, but it is a frequent accompaniment. A good example occurs in the “filling with the Holy Spirit” among Pentecostal church members in Southern Appalachia, a ritual that often culminates with many of the congregation performing glossolalia (speaking in tongues).

11

Abell (1982, 128-130) describes one such event:

[The Evangelist] begins to preach. As he speaks quietly and clearly, he begins to rock forward and then backward. . . . As his voice grows louder, it also becomes more rhythmic, corresponding to the shifting of his weight from one foot to the other. Gradually he begins to lift each foot as he shifts his weight and slams it down as his voice grows to the limits of human vocal intensity. . . . Many persons in the congregation begin to sway side by side or front to back, keeping time with his driving behavior. As the driving becomes more intense, persons close their eyes and begin to manifest rapid quivering of the head from side to side as they continue their backward and forward movement. Some people clap their hands or stomp their feet to the rhythm and semi-audibly praise God. Faces turn red and blue as jerks and quivers become manifest. . . . As [the Evangelist’s] driving behavior approaches its climax, a person may begin to speak in tongues, stand up and dance in the spirit, jerk and shiver, or stand up and shout. After a few minutes of acting out, [the Evangelist] starts again in his quiet, forceful voice. Each cycle from the quiet beginning to the thundering climax lasts from five to fifteen minutes.