The Hunter From the Woods (17 page)

Nearing nightfall, Sofia was a hospital ship without a doctor.

Beauchene had guided his girl back into the smoke and fire to rescue survivors. They’d pulled from the sea fourteen badly burned men and six more who could at least walk. The sharks were indeed already returning to the sea what had walked on land. There was no sign of Manson Konnig’s body. It was going to be a long trip, the rest of the way to England, and there would surely be more canvas shrouds lowered over the side. For some of those burned scarecrows, it would be the merciful thing.

Eight

Javelin

crewmen were found hiding aboard

Sofia

, one of them in the closet of the second of V. Vivian’s unused staterooms. Another was hiding down a ventilation funnel. A third had to be shot because he attacked Olaf Thorgrimsen with a pocketknife.

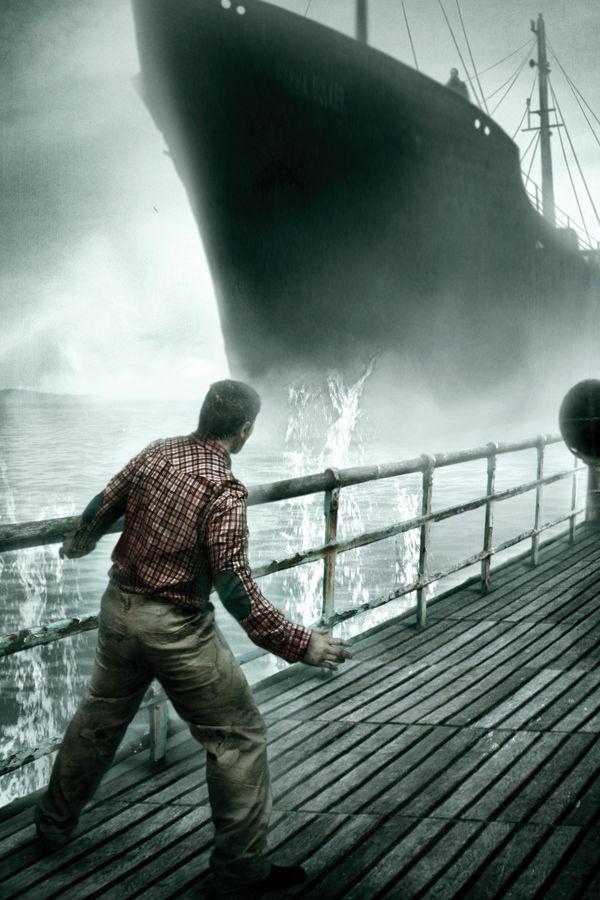

Sofia

was a mess. With the crumpled bow that had crossed her eyes, she could barely make four knots. Multiple leaks forward had been contained and the pumps were at work, but she was badly injured. Rough weather, Beauchene told Michael at a meeting in the mess hall, could bring the sea rushing in through the patches and now they had not a single lifeboat.

Javelin

’s heat had scorched the portside of

Sofia

’s superstructure and blackened her gunwales. The torpedo’s detonation had burst the eardrums and the resultant shockwave had broken the bones of more than one man. Every porthole on the ship had been either blown inward or cracked.

One thing could be said for Paul Wesshauser, in Beauchene’s opinion. The skinny bastard knew how to pack a long dick.

Michael suggested the fans ought to be turned on in the fertilizer hold.

Beauchene and Michael took a walk around the singed deck near seven o’clock. The captain carried his Thompson and Michael his revolver, because two hours ago another

Javelin

crewman had been found curled up under a tarpaulin. Most of

Sofia

’s lamps that still worked had been turned on. The crew was being fed and food was being prepared for the wounded prisoners, who’d been put into one of the forward holds. A dependable Pole had been named first mate and was manning the helm. A radio SOS had gone out and received a reply, and

Sofia

was meeting with the British freighter

Arthurian

for medical help and supplies around ten. Then the Russian, a good day’s work done, went to eat his dinner and get some sleep.

Sofia

’s smashed nose headed west. Above the sea, stars filled the sky.

“She’s not pretty but she’s tough,” Beauchene told Michael as they walked. “I think we’ll make it all the way.

If

we have a calm sea. And

if

those patches hold. Ah, maybe we can get better equipment from your British friends, eh?” He didn’t wait for an answer. “Come on,

mon ami

,” he said, and he reached up to clap Michael on the shoulder. “I’ve got another bottle.”

They climbed the scorched stairs to the wheelhouse, Michael following the captain. A few low lamps burned on the bridge. The first thing the two men saw was that the wheel was unmanned and

Sofia

was just beginning to drift off-course. The second thing was that the dependable Pole lay on the boards on his face with blood on the back of his sandy-haired head.

The third thing they saw was a ragged and burned figure standing in the corridor.

It still had a red goatee. The ebony boots were not now so glossy.

It also held a Luger, and it fired that weapon twice.

Gustave Beauchene cried out and clutched at his left side. He fell to his knees as the Luger trained upon Michael Gallatin.

Michael had no time to draw his own weapon. He propelled himself forward as the Luger barked and a bullet whistled past his left ear.

He hit the ruins of Manson Konnig in the midsection with his shoulder and drove the man back even as he grasped and held the gun hand. The Luger fired again, the bullet thunking into the ceiling. Konnig suddenly showed his strength and tremendous power of will by striking Michael a hard blow between the eyes with his free fist and then swinging him bodily around as his knees buckled. Michael crashed through the door onto the dirty carpet of Beauchene’s cabin.

Dazed, Michael saw the gun rise up again and flung himself aside as a bullet dug splinters from Beauchene’s desk. He got his own weapon out and fired a shot, which went wild over Konnig’s right shoulder. Konnig stood in the doorway, his teeth bared in the dark and melted face, and fired once more as Michael crawled under the protection of the desk. Then Michael lifted the entire desk up and heaved it at Konnig, who retreated into the corridor as papers flew about him and dirty plates clattered against the opposite wall.

A bolt was pulled back.

Konnig’s head swivelled to the right.

Gustave Beauchene, blood blotching his shirt at left side and left shoulder, was aiming his submachine gun. He had a crooked grin on his gray face.

“I’ve come,” he gasped, “to remove the garbage.”

He opened fire.

Michael saw the bullets start at Konnig’s belly and stitch upward along the chest and into the face. Konnig danced a dead man’s jig. A chunk of his head vanished in a red spray. The Luger fired once more from the nerveless fingers, the slug going into the floor.

Beauchene kept firing to the end of the clip, and then Konnig crumpled like a rag doll that had been held over a campfire by a bad little boy.

Konnig’s body twitched and twisted, but without much of a head there was not much of a brain therefore he was strictly yesterday’s news.

He was red all over.

The body was still. Beauchene lowered his Thompson, clutched at his wounded side again and then he too dropped. Michael emerged from the cabin and went directly to the captain’s aid. He tore the shirt open to look at the wounds. Three crewmen alerted by the noise of gunfire, among them Dylan Custis, came rushing into the wheelhouse and gathered around Michael and the captain.

“For Christ’s sake,” Beauchene asked them, “what’s the fucking fuss?” He blinked heavily, struggling to focus. “Haven’t you ever seen a man who needs a

drink

?”

p

It was a sunny morning when

Sofia

made harbor in Dover. The lines were thrown and secured, the anchor was dropped, and the ugliest ship that had ever crossed under the view of Dover Castle was safe. The gangplank went down, and the journey was done.

Several black trucks and ambulances were waiting, as well as two polished black sedans. Another crew came on to unload the cargo. The cranes moved and the hoists rattled. Blinking in the English sun, the men walked off

Sofia

carrying their duffel bags and strode off along the pier either alone or in groups: Olaf Thorgrimsen, soon to be bound back to Norway on another ship, and Dylan Custis, eager to visit his wife in Croydon; the engineers, electricians, mechanics, carpenter and welder; the able seamen and the ordinary seamen; the men of many nations but now the rather proud owners of one citizenship.

The freighter trash.

Marielle Wesshauser and her family had been met by some men she knew must be important. One of them was very tall and boyish-looking, though he was probably in his late forties. He had silvery-blonde hair and pale blue eyes. He had a high forehead, so he must be smart. Freckles were scattered across his cheeks and the bridge of his crooked nose. He talked quietly to her father and kept eye-contact. He seemed very cool and collected. She’d seen that same man speaking to Captain Beauchene on deck not long ago, and he’d spoken that very same way. Afterward, he and Captain Beauchene had shaken hands and then Marielle had watched the Frenchman wander around the ship. It seemed he was touching everything he could, as if saying goodbye to someone he’d once loved.

But she understood now that one had to look ahead. Always ahead. And that one had to keep working at life. Working at it, all the time. Working and working, like Vulcan at his forge.

For how else would anything beautiful be created?

They were leaving now, she and her family. The important men wanted to put them in one of the black sedans and take them to a hotel in London. That would be very much fun, Marielle thought. It would be very exciting, to walk around in London.

But first…

She searched and searched. Then she searched some more.

She looked everywhere.

But the gentleman was gone.

“Come on, Marielle! It’s time!” said her father, who offered her his hand as usual to negotiate any precarious path, such as the gangplank.

But she decided she didn’t need his hand today. Today she felt the sun on her face, and today she felt so light.

Because Billy was standing at the bottom, waiting for her, and when he saw her he smiled and came up to meet her halfway.

The

Wolf

and the

Eagle

One

“Buckle up, Major.”

The major was already buckled up.

“Short flight today, sir.”

“If you say so,” said Michael Gallatin, who occupied the rear seat of the RAF Westland Lysander aircraft. He was wearing his khaki British Western Desert Force uniform, sun-bleached and dusty, consisting of a sweat-damp short-sleeved shirt, shorts, gray knee-socks and tan-colored ankle boots. Around his neck and into his collar was tucked a dark blue scarf. It was meant to keep out the chafing grit that could lead to not only great mental distress but to serious infection, particularly if the flies got their diggers in the wound. His officer’s cap was the same color as the Libyan wasteland, the hue of the endless sand and the countless stones. Crammed into the space under his boots was his kitbag. It held a change of clothes, his canteen, his shaving accoutrements and his dependable American Colt .45 automatic. He wore his insignia of rank at a slight angle, which did him no good with superior officers but earned the silent approval of those below; in any case, the superior officers had been informed to leave him alone by the letter he carried from a very important man in London.

“Weather’s fine for flyin’ this mornin’, sir,” said the young Cockney pilot, whose sidelong grin displayed his crooked front teeth. He was enjoying an obvious moment of mirth concerning his rather nervous passenger. “No reason to worry.”

“Who’s worried?” Michael fired back, a little too quickly. In the North African desert in mid-August a clear sky could never be called upon to lift the spirits. It might be cloudless but it was often a pale milky color more white than blue, as if that cruel sun had burned all the beauty even out of Heaven. “You just tend to the flying,” Michael said, and told himself to relax. Easier told than done. He didn’t relish flying very much; it was a combination of his distrust—one should not call it

fear

, of course—of confinement and heights, and the whole idea of sitting in a sputtering machine many thousands of feet above the earth seemed even more unnatural to him than a sea voyage.