The Hunt for the Golden Mole (6 page)

Read The Hunt for the Golden Mole Online

Authors: Richard Girling

The story of the Tennessee mice was told by an American psychologist, Harold A. Herzog, in the

American Psychologist

magazine. He drew the obvious conclusion. The moral judgements that humans make about other species âare neither logical nor consistent . . . The

roles

that animals play in our lives, and the

labels

we attach to them, deeply influence our sense of what is ethical.' In plainer language, we are prejudiced. Our attitudes to animals are determined by the labels we attach to them â

pet

,

food

,

pest

,

vermin

. Shuffle them around, and the result is almost viscerally disturbing. Pony-veal? Cat-traps? A dog-shoot? Moral duplicity is inescapable. A few months ago I paid a man to put ferrets down the rabbit holes in my garden, to flush out and snap the necks of the wild breeding stock. Later the same day, like a repentant Mr McGregor, I offered fresh carrots to my neighbours' pet rabbits. Afterwards, with a glass of good red burgundy in hand, I enjoyed a pie made from one of the ferreter's victims. There is no moral consistency in any of this; only a kind of self-interested pragmatism. At the very same time as I was developing my fascination with the Somali golden mole, I was laying traps for the all too common-or-garden local mole,

Talpa europaea.

The one is rare to the point of invisibility; the other abundant to the point of nuisance. Two similar species; two very different attitudes.

There is no reason to wonder, therefore, how it was that Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming made such distinctions between dog and wild beast. They were irrational, but they were not incomprehensible. And he was in good company. Back home in Europe and America, public interest in zoological exotica was such that showmen like P. T. Barnum and the Ringling Brothers could make fortunes from it. And science, too, had much to learn from the hunters' specimens. In its early years even the Zoological Society of London owned more dead animals than live ones, and museums of natural history throughout the world relied on the bullet to fill their display cases. With all due reverence, one recent writer describes the great Central and North Halls of the Natural History Museum in London as a âValhalla for British natural history'. Here stand memorials to the museum's first superintendent, Richard Owen, and to the secular gods Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. Owen, who loathed Darwin and all his works, stands gowned on his pedestal,

hands outstretched like a prophet in mid-sermon. Darwin himself sits cross-legged in his chair, hands in lap, as if resting from the burden of his own huge brain.

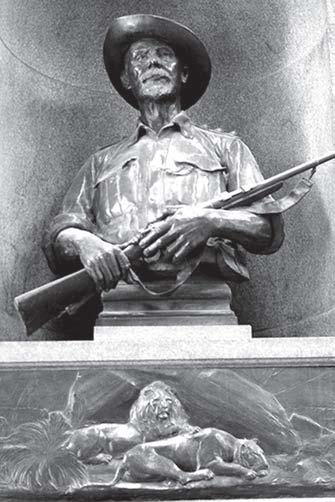

But there is another, more flamboyant figure, a man in a bush hat brandishing a rifle above a bas-relief of lions. This is the hunter, explorer and naturalist Frederick Courteney Selous (1851â1917), the real-life inspiration for Rider Haggard's fictional adventurer Allan Quatermain. The presence in Valhalla of a famous killer, arguably the deadliest white hunter ever to load a gun, is not an aberration. In honouring him with a bronze, the museum was simply acknowledging its debt. Men like Wallace and Darwin may have given the museum its

raison d'être

, but it was men like Selous who filled its display cabinets. His marksmanship in Africa provided the museum with jackals, hunting dogs, hyenas, lions, leopards, cheetahs, buffaloes, antelopes, gazelles, wildebeest, reedbucks, waterbucks, bushbucks, kudus, elands, elephants, giraffes, warthogs, hippos, zebras, rhinos and elephants. From elsewhere in the world came wolves, otters, lynxes, bison, goats, chamois, deer, moose and reindeer.

Alas for me, he never shot a Somali golden mole. More ominously in retrospect, neither he nor Gordon-Cumming ever killed a bluebuck

(Hippotragus leucophaeus)

. This was not by accident or because they thought it to be not worth the price of a bullet. In 1799, twenty-one years before Gordon-Cumming's birth and fifty-two years before Selous's, this large South African antelope, also known as the blaubuck or blaauwbock, had passed from the veldt into the history books â the first large mammal in historic times to be hunted to extinction.

M

en like Gordon-Cumming and Selous must have known something about the way species interacted, and have had some idea that the tiniest scraps of life at the bottom of the food chain were in some way important to the behemoths at the top. But they were showmen as much as naturalists, and their audiences were not much attracted by small and drab. Who would queue to see a mole? Who knew or cared anything about âecology' (the word did not even exist until coined by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel in 1866). People wanted drama â living colour and bold brushstrokes. Everything else could bide its time. Most species of golden mole were not described until after Gordon-Cumming's death, and

Calcochloris tytonis

had to wait until 1968. It may be commonplace now to talk about âbiodiversity', âecosystems' and âsymbiosis', but these are modern concepts built jigsaw-fashion over decades. The hunters saw only what was in front of them, one species at a time, biggest first. Who could be surprised that they showed little interest in anything smaller than a dik-dik?

Given the challenges of surviving the African climate, never mind the impossibility of heavy haulage through unmapped forests and plains, it is easy to understand why most of the trade was in heads, horns, tusks and skins. A man with an ox-cart and

a rifle â even one as resourceful as Gordon-Cumming or Selous â was not going to bring home a fully grown live hippopotamus. The Natural History Museum would have been nothing without marksmen and taxidermists. There is no irony, intentional or otherwise, in the elevation of Selous to its pantheon of heroes.

All the same, showmen knew very well that live action would sell better than static display, and zoos by definition needed life. There was a powerful incentive to âBring 'em back alive', as the twentieth-century Texan adventurer Frank Buck would put it in the title of his bestselling book. The problem was that wild animals did not travel well. What started out alive was more than likely to be delivered dead, and few of the survivors would last long in captivity. It was a vicious circle. The high mortality rate only increased the demand for replacements, thus inflating the prices and attracting the kind of entrepreneur for whom the scent of a fast buck was made no less sweet by the stench of corpses. But again we have to understand the spirit of the age. Men in the early nineteenth century did not inflict upon other species any cruelty they were not willing to inflict upon their own. The slave trade in the British Empire was abolished only in 1807, and slavery itself remained legal until 1833. Even during the lifetime of my grandfathers, in the 1890s, African and Arab slave traders were still resisting attempts to close them down. Despite the establishment of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1824, and of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1866, there were very few curbs, legal or moral, on the worldwide trade in birds and beasts.

The heightened sensitivity of the twenty-first century would have been as impossible for the nineteenth century to imagine as the loss of Victoria's empire. Our double standards might have struck them as absurd. On my way to see London Zoo's

okapi, I linger in the giraffe house, and I ask myself: What do I think about this? Where is my moral centre of gravity? I try to work out how I score. On killing for sport I have a clean sheet. Never done it; never will. People who stand in fields and pick off tame pheasants strike me as, at best, laughable. Great white hunters, eh? Beyond that I am in difficulty. My misgivings about pet-keeping are compromised by the cats and guinea pigs beneath the plum tree in my garden. My tolerance of other species sharing my space is widely variable. I won't tread on an ant if I can avoid it, and I work at a desk under a tent of undisturbed spiders' webs, but I've killed rabbits and moles, and there are mouse-traps in the kitchen. I eat meat, lots of it, and I have made a public defence of animal laboratories. Nobody could mistake me for a Jain. The zoo therefore triggers a maelstrom of conflicts. The giraffe is not a threatened species. Its range in sub-Saharan Africa has been sadly reduced, and there may be uncertainties about its long-term future, but the IUCN calculates a viable wild population in the region of 100,000 and classifies it as a species of least concern. Its survival does not depend on conservation by zoos. I ought therefore to feel unease, perhaps even indignation, at the sight of these miraculous creatures in confinement so far from their natural habitat. But I don't. Wherever in the world I go, I am unlikely to come across a happier contrast than between these sleek, apparently contented animals and their unfortunate historical forebears who might have died for nothing more than their fly-whisk tails. I pass on with contradictions unresolved. Situation normal.

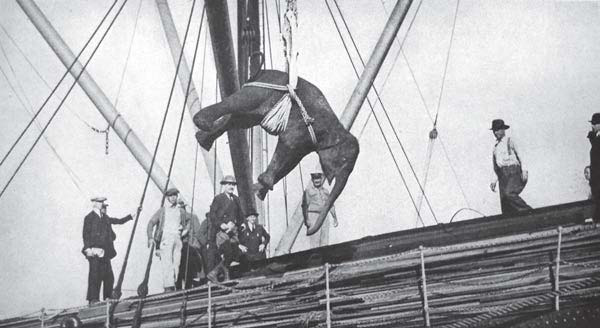

High risk â big animals were frequent victims of accidents at the docks

All trafficked animals in the nineteenth century suffered in handling, but the giraffes' great height, their long necks and gangling limbs, made them particularly vulnerable. Being the most awkward of cargoes, they all too easily fell from dockside cranes. In 1866 two were killed in a fire at London Zoo. In 1876 at Hamburg, three more broke their necks against a wall. In the wild, where they loomed high above the low African skyline, they drew a dangerous amount of attention to themselves. Along with the golden moles, aardvarks and hippopotami, they were counted among the âvery peculiar forms of mammalia' celebrated by Alfred Russel Wallace, and were conclusive evidence of Africa's weirdness. No animals ever caused more of a stir in Europe than the first giraffes, delivered in 1827 by the Viceroy of Egypt as gifts to the British and French governments. They were also easy to shoot, and provided men like Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming during their travels with a regular supply of meat. He reminds us again of the cheapness of animal life:

As we neared the water I detected a giraffe browsing within a quarter of a mile; this was well, for we required flesh . . . He proved to be a young bull, and led me a severe chase over very heavy ground. Towards the end I thought he was going to beat me, and I was about to pull up, when suddenly he lowered his tail, by which I knew that his race was run.

Urging my horse, I was soon alongside of him, and with three shots I ended his career.

Another day he chased and shot âthe finest bull' in the herd, but took nothing from it but the tail. It was against this ingrained tradition of kill-as-you-go that the live animal traders moved in and developed their businesses. There would be changes in practice but not in outlook. The merchants were not monsters â memoirs reveal some concern for animal welfare â but they were pragmatists who accepted the crude realities of their trade. Purposely or by accident, they would waste as many lives as it took to satisfy their customers.

Where big animals such as giraffe and elephant were concerned, the safest option for a trapper was to target the young. If anything, this actually increased the number of dead. Before you could catch a baby you had to kill its mother and the herd leaders that would defend it. Losses of breeding stock were immense. A zoo official in London reckoned that the price of one live orang-utan was four killed in the wild. Yet this was only the beginning. There is no record of how many captive animals died on the journey from forest or veldt to the coast, but on the evidence of later chroniclers such as Frank Buck we may assume the number was huge. Even that was not the worst of it. Of those that survived long enough to go aboard ship, half were lost at sea.