The History of Florida (91 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Johnson from Texas, Jimmy Carter from Georgia, and Bil Clinton from

Arkansas). As the GOP began winning races, they began attracting even

more party identifiers once there was a viable option to the Democratic

Party. However, as late as 1979, no statewide political office was held by a

Republican, and only 26 percent of the seats in the legislature and three of

fifteen congressional seats were held by Republicans.25

By 1990, the party had become so influential that it even constituted a

powerful force in north Florida, a region where residents would have turned

over in their graves before voting Republican in the period before 1960. In

1994, for the first time in the twentieth century, Republicans seized power in

the state Senate. Republicans also held one of the two U.S. Senate seats and

more than half of the Florida seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and

barely lost the governor’s race.

434 · Susan A. MacManus and David R. Colburn

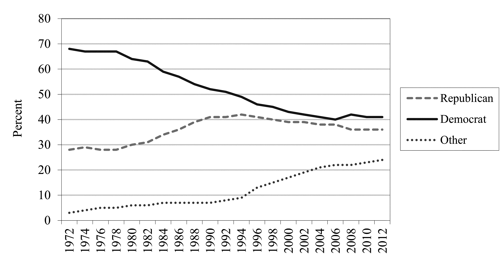

Florida Voter Party Registration Percentages: 1972–2012. Source: Compiled from data

from the Florida Division of Elections.

It was the highly contentious 2000 presidential election, when Demo-

crat Al Gore from Tennessee came within 537 votes of winning Florida,

that sealed Florida’s position as one of the nation’s perennial premier battle-

ground states. Presidential and gubernatorial races now routinely go down

proof

to the wire, with virtual y each successive poll showing a lead change. Inde-

pendents have become the fastest growing portion of the electorate and the

most volatile and unpredictable. In 2008, independents helped turn Florida

blue for Democrat Barack Obama, then red in 2010, helping to elect Re-

publican Governor Rick Scott and Republican U.S. Senator Marco Rubio.

Florida’s independents are, on average, younger than the state’s Democrats

and Republicans and the “swing voters in the swing state.”

Geographical y, north Florida remains a Democratic region of the state if

measured by party identification and registration. But it looks Republican if

measured by votes in presidential and gubernatorial elections. (The region

often votes Republican in those contests, especial y when Democratic candi-

dates are too liberal.) The southeastern part of Florida, particularly Broward

and Palm Beach Counties, is strongly Democratic while the southwest re-

gion is the most heavily Republican area. Central Florida, specifical y the I-4

Corridor (the Tampa Bay and Orlando media markets), has evolved into the

most competitive part of the state.26 The I-4 Corridor is home to nearly half

(44 percent) of all the state’s registered voters and is almost equal y divided

between Democrats and Republicans, with a sizable and growing number of

Florida Politics · 435

independents. The area is considered to be a microcosm of Florida at large

in both its registration and voting patterns.27

The strength of the Republican Party in Florida lies with white voters,

Cuban Hispanics, men, and more affluent, Protestant, col ege-educated,

and conservative voters. Democrats draw greater support from blacks,

some non-Cuban Hispanic groups, women, Jewish and nonreligious per-

sons, lower-income, less-educated, and liberal voters. Support levels for

each party’s candidates may differ within these groups, depending on who is

running, their platform, and their leadership skil s during stressful times.28

Fifty Years of Population Growth (1960s to 2010s): An Increasingly

Divided Electorate, Difficult Issues

Population growth created big challenges in a number of policy areas, in-

cluding education, crime and law enforcement, transportation, taxation

(equity), the environment, immigration, and health care. Depending on the

specific policy debate, the state’s historical divides became quite evident:

regional—north vs. south; nativity—old-timer vs. newcomer; racial—black

vs. white, or multiracial with the burgeoning Latino population; ideologi-

cal—conservative vs. liberal; generational—young vs. old; and partisan—

proof

Democrats vs. Republicans.

Even the term “economic development” generated divisive politics, de-

pending on whether it was a high-growth or stagnant economy. During

high-growth periods, Florida’s elected officials faced intense cross-pressures

from citizens. Some pressured them to restrict growth or at least be smarter

about it, while others favored continuing pro-growth policies. During eco-

nomic downturns, there were disagreements about how to jump-start the

economy. Some citizens pushed officials to offer tax breaks to bring new

businesses (jobs) into the community, while others preferred higher taxes

to create jobs, prevent more business closures, and stem further population

out-migration.

Each governor who served from the 1960s to the 2010s had to deal with

some type of crisis during his administration.29 Claude Kirk dealt with a

teacher strike, Bob Graham with the Mariel boatlift from Cuba to South

Florida, Bob Martinez with a revolt against a proposed services tax, Lawton

Chiles with Hurricane Andrew and widespread wildfires in central Florida

during a drought, Jeb Bush with four Category 3 or higher hurricanes in six

weeks, Charlie Crist with the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, and Rick

436 · Susan A. MacManus and David R. Colburn

Scott with a budget crisis (a shortfall of almost $4 billion), a jobs crisis (one

of the highest state unemployment rates in the country), and an ongoing

housing crisis (with one of the highest home foreclosure rates in the coun-

try). In many ways, their successes and failures reflected the social, eco-

nomic, and political landscape of the day. For some, it was their leadership

style and skil s that better explained their tenure in office.

Claude Roy Kirk Jr.-R (1967–1971)

Kirk won the last gubernatorial election in the 1960s before the new con-

stitution and the new court-ordered redistricting took hold. He broke the

Democratic monopoly on the governor’s office by splitting the Democratic

vote (conservative north Florida Democrats vs. the more liberal south Flor-

ida Democrats). He defeated Miami mayor Robert King High, who was per-

ceived by many central and north Florida Democrats as too liberal on civil

rights. Kirk’s administration was both colorful and controversial, marked by

confrontations with the Democratic legislature, an unprecedented statewide

teachers’ strike, and crises over forced school busing. On a more positive

note, he did take some pro-environmental stances, helping to stop the Cross

Florida Barge Canal from cutting across the state. His personal flamboyant

proof

leadership style came under attack from media around the state and turned

off many former supporters. He was defeated in his bid for reelection in 1970

by a young Pensacola Democratic state senator, Reubin Askew.

Reubin O’Donovan Askew-D (1971–1979)

With a new constitution in place allowing governors to serve two terms, re-

formulated legislative districts based on population rather than county, and

a fast-growing population, Askew successful y pushed comprehensive tax

reform through the state legislature during his first term. Askew’s corporate

tax referendum won with over 70 percent of the vote. When the legislature

failed to pass his “government in the sunshine” amendment, he lent his sup-

port to a citizen’s initiative that won nearly 80 percent of vote. He failed in

subsequent efforts to reform the cabinet system and strengthen the gover-

norship, suffering voter rejection in 1978 of constitutional revisions that he

supported. As a progressive Democrat from north Florida, Askew was able

to reunite the Democratic base. He easily won reelection in 1974 to become

the first Florida governor to serve two four-year terms. Askew named the

Florida Politics · 437

first African American to the Florida Supreme Court and appointed the first

woman to the Florida cabinet.

Daniel Robert “Bob” Graham-D (1979–1987)

Although from south Florida, Graham was a moderate Democrat who cap-

tured much of the same constituency that had voted for Askew. He main-

tained a moderate-to-conservative image—tough on crime and willing to

sign death warrants to implement capital punishment. Education was his

passion. He was a forceful advocate for public education, particularly higher

education. He was easily reelected in 1982, as voters perceived that he was

an effective leader who worked well with the Democratical y control ed

legislature. Graham pushed the far-reaching 1985 Florida Growth Manage-

ment Act through the legislature. Among the more controversial provisions

of this act was a “concurrency requirement” that barred private develop-

ment, unless supporting public facilities (roads, schools, sewers, etc.) were

either already in place or were built concurrently with new development.

(The Growth Management Act was significantly altered in 2011 during an

economic downturn when it was regarded by the Republican-control ed

legislature as halting job growth.) Graham’s flair for populism was evident

proof

in his famous “Workdays” that had begun during his first campaign and

continued after his governorship.

Robert “Bob” Martinez-R (1987–1991)

A former Democratic mayor of Tampa took advantage of the state’s con-

servative leanings in 1986 and used extensive television advertising to suc-

cessful y label his Democratic opponent, Steve Pajcic from Jacksonville, as

an unrepentant liberal. Martinez ran on a platform of low taxes and social

conservatism. He lost support by first supporting—and later disavowing

and repealing—a sales tax on services that would have enlarged the state’s

tax base. He also cal ed an unsuccessful special session on abortion and

general y had a difficult time with the Democratical y controlled legislature.

The tax issue doomed him political y, and he lost his 1990 bid for reelection

to Democratic U.S. Senator Lawton Chiles. The issue overshadowed some

of Martinez’s most significant accomplishments. He initiated and expanded

a number of environmental initiatives, creating for the first time uniform

policies for the management and protection of Florida’s surface waters.

438 · Susan A. MacManus and David R. Colburn

Martinez also played a major role in pushing Florida’s Republican Party

toward a more pro-environment position that ended up helping the party

well beyond his tenure as governor.

Lawton Mainor Chiles Jr.-D (1991–1999)

In the first two years of his term, the moderate Democrat from Polk County

faced tough budget times due to the national recession. He, like his prede-

cessors, sought to revamp the state’s tax system to make it more productive

and fairer. He had little success.

Chiles

was

the

first

Democratic

governor

to

face

a

legislature

control ed

by

the

opposition

party

. In the 1992 midterm elections, the Republicans won a 20 to 20 tie in the state Senate and in 1994,

a majority of the seats in both houses. Chiles barely won reelection in 1994

over Republican Jeb Bush by touting his more conservative policy positions

on prison building, the death penalty, and opposition to unchecked immi-

gration. Chiles joined with some other border state governors in suing the

U.S. government to recover the costs of providing services to illegal immi-

grants. They lost the suit, but the governor’s position resonated with Florid-

ians. In his second term, Chiles’s most notable success was a lawsuit against

the tobacco industry demanding compensation and punitive damages for

proof

the il effects of cigarette smoking on state-supported Medicaid patients.

With the settlement funds he was able to expand health care opportuni-

ties for Florida children who lacked health care. Tragical y, Chiles died of

a heart attack in the gym of the Governor’s Mansion with just twenty-four

days remaining in his term. Lieutenant Governor Buddy MacKay filled out