The History of Florida (47 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

territorial government. Executive and legislative leadership for the territory

would come from a governor, a secretary, and a legislative council—all to

be appointed by the president. Federal courts were established at Pensacola

proof

and St. Augustine, with judges to be appointed by the president. Only the

delegate to Congress would be elected.

Governor Duval cal ed the first Legislative Council into session on 10

June 1822 at Pensacola, but the ship carrying the St. Johns delegates that

departed St. Augustine on 30 May experienced storms and shipwreck and

did not arrive until 22 July. Another shipwreck claimed the life of a council

member. A yellow fever outbreak forced the council members to reconvene

at temporary quarters north of Pensacola and claimed the life of the chair-

man, Dr. James C. Bronaugh. Despite these adversities, the first council cre-

ated civil offices, courts, a militia, and revenue measures and carved two

new counties, Duval and Jackson, from the unmanageably large counties of

St. Johns and Escambia.

Congress ordered that annual sessions of the council should alternate be-

tween St. Augustine and Pensacola, but dangers and delays experienced by

the delegates from Escambia to the 1823 session in St. Augustine convinced

Governor Duval that the system was untenable. He commissioned Dr. Wil-

liam H. Simmons and John Lee Williams to select a compromise site for a

permanent capital between the Ochlockonee and Suwannee Rivers, mid-

way between St. Augustine and Pensacola. Simmons and Williams selected

U.S. Territory and State · 223

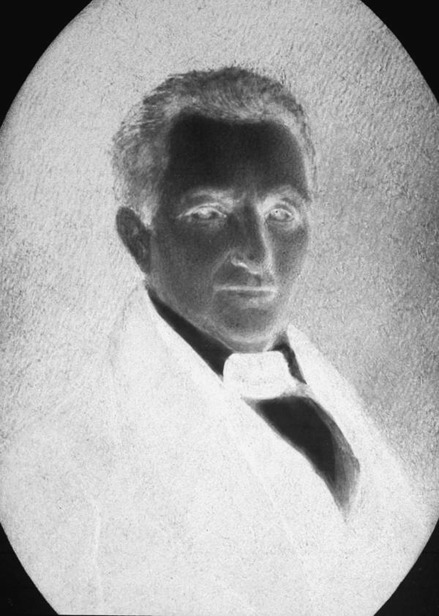

Portrait of William P. Du-

val. Courtesy of the State

Archives of Florida,

Florida

Memory

, http://flori-

damemory.com/items/

proofshow/128200.

Tal ahassee, where the old fields and council houses of the Apalachee once

stood.

Hernando de Soto had camped near the site of the new capital in the

winter of 1539–40; Franciscans built missions there a century later; and in

the eighteenth century, Creek migrants established Tal ahassee Taloofa, and

Mikasuki, towns that were burned by Andrew Jackson’s army in 1818. The

opposition of Seminole leaders Neamathla and Chefixico was disregarded,

and Tal ahassee became the permanent capital in March 1824.

Settlers began arriving at the site in the following month, living in tents

while they acquired land and built houses. By the time the council met in

November 1824, a hotel had been constructed for legislators. Governor Du-

val lived briefly in a log cabin adjacent to the site of the log-and-board struc-

ture that became the Capitol in 1824. A two-story brick building replaced

the log building in 1826, and was in turn superseded by a more permanent

structure in 1839.

Congress made the legislative council elective in 1826, and bicameral in

1838. Members of the House of Representatives were elected at the county

224 · Daniel L. Schafer

level based roughly on population, and the initial eleven senators were cho-

sen from four judicial districts, with three each from the east and west,

four from the middle, and one from the sparsely populated south. The most

important elected official in the territory was the delegate to Congress, al-

though the first delegate was appointed by the legislative council. Joseph

M. Hernández, an East Florida planter and lawyer of Minorcan ancestry,

was selected for the 1823 term. Hernández was the first Hispanic to serve in

Congress. Subsequent delegates were elected by the voters of the territory,

with suffrage open to white males at least twenty-one years old who had re-

sided in the Florida Territory for at least three months. In the 1824 elections,

Richard K. Call became the first elected delegate.

Delegates from Florida were not eligible to vote in Congress, but they

were able to lobby for the interests of residents of the Territory. Hernández

and Cal , as well as subsequent delegates advocated for naval projects, road

construction, bridges, and other internal improvements. Joseph M. White

served as delegate from 1825 to 1838. By the time his successor was elected,

candidates were pledged to political parties. Charles Downing was elected

as a representative of the Whig Party.

Until Florida became a state in 1845, its governors were presidential ap-

pointees. Wil iam Duval served until 1834, when President Andrew Jack-

proof

son appointed John H. Eaton to succeed him. Richard Cal , still a Jackson

favorite despite his opposition to Democratic Party policies in Florida, was

appointed governor in 1836. President Martin Van Buren replaced Call with

a Democrat, Robert R. Reid, in 1839. Call supported Whig Party candidate

William Henry Harrison’s successful presidential campaign in 1840 and was

rewarded with a return to the governor’s office from 1841 to 1844. Democrat

John Branch served as governor for the last year that Florida was a territory.

During the early territorial years, Florida residents were more concerned

with acquiring and cultivating land than with political affairs in Tal ahassee.

Some had migrated to Florida even before it became an American territory.

More than 450 settlers from the United States were living near Pensacola

prior to final approval of the Adams-Onís Treaty. Two thousand Americans

had marched with Jackson from the Suwannee River to Pensacola in 1818.

Some remained, and others returned home to tell family and friends of the

fertile and unclaimed land they had seen, prompting land-hungry pioneers

on the southern frontier to move to Florida.

The journalist and historian Clifton Paisley identified 300 persons living

in log cabins and planting crops at the Spring Creek settlement in north-

western Jackson County in the months before the Stars and Stripes were

U.S. Territory and State · 225

raised at Pensacola. By 1825, Jackson County had 2,156 residents, a group

that included cotton planters and approximately 720 enslaved black men

and women. In 1819, Henry Yonge was living in today’s Gadsden County on

the Apalachicola River after migrating from Georgia with twenty slaves. He

was already clearing land and erecting buildings, waiting for the American

flag to catch up.

Middle Florida, between the Apalachicola and the Suwannee Rivers, at-

tracted the majority of settlers in the territorial years. Tal ahassee grew to

1,500 residents by 1835, a combination government town and merchant cen-

ter. Men from aristocratic families in Virginia and Maryland brought large

numbers of slaves to cultivate sugar and cotton in the fertile Red Hil s of

Florida. Thomas E. Randolph and his son-in-law, Francis Eppes, a grandson

of Thomas Jefferson, settled in today’s Leon County. John G. and Robert

Gamble migrated from Richmond, Virginia. Thomas Randal , Wil iam B.

Nuttal , and Hector Braden also came from Virginia.

Thomas Brown arrived in Middle Florida during the winter of 1826–27

with an advance party of slaves that immediately built shelters, cleared land,

and planted crops. In 1828, Brown led a wagon caravan of twenty-one plant-

ers, their families and slaves, from Virginia to Middle Florida. Brown him-

self brought 140 slaves to Florida. Following statehood, Brown was elected

proof

governor, serving from 1849 to 1853.

Dr. John A Craig migrated from Maryland. Benjamin Chaires, the

wealthiest of the Middle Florida planters, moved from North Carolina.

James Gadsden came from South Carolina, Richard K. Call from Virginia

via Kentucky, and Joseph White from Kentucky. Prince Achille Murat, son

of the exiled king of Naples and married to the sister of Napoleon Bonaparte,

created Lipona, an estate in Jefferson County known for elegant entertain-

ment. With such personages, Middle Florida became the center of an aristo-

cratic social life and the dominant political and economic region of Florida

from 1821 to 1861.

Census takers counted fewer than 2,400 persons living in Middle Florida

in 1825 and 11,000 in the rest of the territory. By 1830, Middle Florida had

grown to nearly 16,000, approximately 45 percent of the territory’s total

population. Ten years later it had 34,000 residents, West Florida only 5,500,

and East Florida 15,000. The Middle Florida counties, where the majority

of the population consisted of enslaved blacks, harvested 80 percent of the

cotton produced in Florida in 1840.

Migrants came to East Florida as wel , many fording the St. Marys River

and following the King’s Road to homesteads in today’s Nassau and Duval

226 · Daniel L. Schafer

Counties. Others continued southward, crossing the St. Johns River at a

narrow bend known as Cowford. They found the best land already under

cultivation by families who had been living in the area for decades. The

family of Francisco Xavier Sánchez witnessed three changes of flags at St.

Augustine, and acquired cattle ranches and plantations as early as the 1670s.

Francis P. Fatio’s family lived on St. Johns River properties acquired from the

British government in the 1770s. Francis Richard arrived in 1791, in flight

from the violence associated with the slave rebel ion in Saint Domingue.

By 1821, the Richard family had acquired a sawmill and thousands of acres

of prime woodlands and plantation fields. There were also Browards, Wil-

liamses, Christophers, Houstons, Flemings, McIntoshes, Clarks, Perpalls,

Solanas, Ugartes, Bethunes, and Hartleys among the families with long ten-

ure in northeast Florida.

Zephaniah Kingsley, an African slave trader, maritime merchant, ship-

builder, and planter, arrived in northeast Florida in 1803. The African

woman he acknowledged as his wife and emancipated, Anna Madgigine Jai

Kingsley, a woman from a royal family in Jolof, Senegal, became a planter

and slave owner herself. In 1821, Kingsley lived with his free African Ameri-

can family at Fort George Island, where the St. Johns River meets the At-

lantic Ocean. He acquired title to numerous plantations located in what

proof

became six northeast Florida counties, cultivated by more than 300 slaves.

Slave Quarters at Kingsley Plantation, Fort George Island

. Stereographic image, ca. 1870.

Courtesy of Kevin Hooper, Middleburg, Fla.

U.S. Territory and State · 227

For Isaiah David Hart, another longtime resident of northeast Florida,

the exchange of flags and the onrush of migrants was an opportunity to

profit. One of the Patriot rebels in 1812–14, Hart was living on the St. Marys

River at the time the treaty of cession was signed, one of the

banditti

raiding

for cattle and slaves. In 1820, he traded cattle for acreage near the ferry cross-

ing at Cowford on the St. Johns and built a boardinghouse and store. The

acreage became the heart of the town of Jacksonville when it was founded

in 1822, and Hart became a wealthy merchant, planter, and influential

officeholder.

In 1821, St. Augustine was the only town of significant size in East Florida.

Greek and Minorcan descendants of the failed Smyrnea settlement estab-

lished by Dr. Andrew Turnbull (today at New Smyrna Beach and Edgewa-

ter), occupied one-quarter of the town; Anglo-Americans, Europeans, free