The History of Florida (108 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

football teams achieved astounding levels of success), by professional foot-

ball teams in Miami, Tampa, and Jacksonville, by the Miami Marlins and

Tampa Bay Rays Major League Baseball teams, and by professional basket-

ball and soccer franchises. The improbable presence of two professional ice

hockey teams in Florida is a testament to Sunbelt technology, economics,

and demographics.

Sports, retirement, and tourism have helped shape Florida’s image and

propelled its economy. But in the years after World War II, powerful new

forces of change emerged. The war itself had a tremendous impact. Military

training facilities, air bases, naval bases, and major shipyards sprouted all

516 · Raymond A. Mohl and Gary R. Mormino

over the state. Service personnel and their families migrated to Florida, and

many thousands returned to live when the war was over. Miami, Tampa,

Jacksonville, and Pensacola especial y benefitted from military investment

and enormous military payrol s. Huge federal wartime expenditures in

Florida and throughout the Sunbelt produced essential new infrastructure,

supported local economies, and stimulated construction and service in-

dustries. By the 1980s, defense spending and military payrolls in Florida

surpassed $15 bil ion annual y. Underlying much of the nation’s changing

economic and urban pattern in the postwar era has been the redirection of

federal resources through military and defense spending, and this “military

remapping” of America had special salience for Florida in the second half

of the twentieth century. With the end of the Cold War, however, the federal

military-industrial complex, once so vital to Florida’s defense industries and

military bases, began to shrink. In 2011, NASA ended the three-decade-long

U.S. space shuttle program, causing massive layoffs. The Kennedy Space

Center’s workforce has been drastical y reduced to 8,500 workers, the smal -

est number in more than three decades.

proof

[Fig 25.4] In 1959, a Pratt and Whitney engineer monitors a jet engine test in Palm

Beach County. The 1950s marked the beginning of a dramatic increase in the number

of industries that took root in Florida. In addition to Pratt and Whitney, these included

Martin Aircraft, Sperry Rand, IBM, Maxwell House, Anheuser-Busch, and Disney World.

The last-named corporation opened the Magic Kingdom in 1971 and Epcot Center in

1982, which together would draw more visitors each year than Florida had residents.

Boom, Bust, and Uncertainty: A Social History of Modern Florida · 517

proof

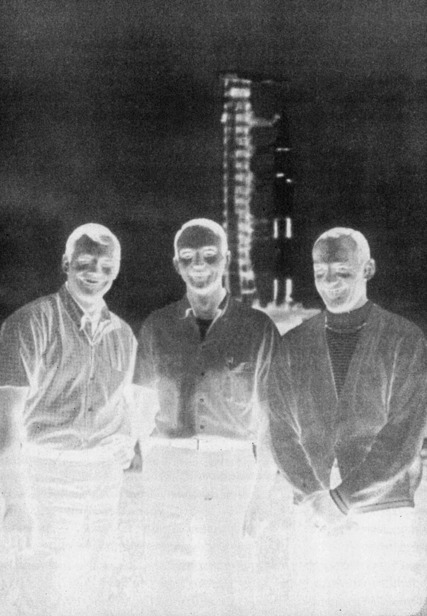

No event in its history brought Florida more national and international notice than did

the launch of Apollo XI from Cape Kennedy on 16 July 1969. The rocket and space ve-

hicle enabled American astronauts Neil A. Armstrong (

left

) and Edwin E. Aldrin (

right

)

to become the first humans to walk on the surface of the moon. At the center of this

photograph, taken beforehand, with the launch pad in the background, is Michael

Collins, pilot of the mission command module.

The postwar federal presence was important, but a series of powerful eco-

nomic changes also shaped post-1950 Florida. Scholars have begun to sketch

the full dimensions of a long-term structural transformation of the Ameri-

can economy that dates back to the 1950s—a process of “deindustrialization”

that has resulted in the dismantling and abandoning of much of the nation’s

increasingly obsolete industrial infrastructure. Taking the place of the aging

Rustbelt factory industries are the dynamic new industries of the postin-

dustrial economy—the high-tech, computerized information businesses

518 · Raymond A. Mohl and Gary R. Mormino

and the more ful y developed (and low-paying) service economy. The new

American economy grew up around services provided by government, edu-

cational agencies, and financial services companies; it was spurred also by

health care and medical delivery, food service, travel and entertainment,

and retailing and consumerism. Fast food, motel chains, and car rentals,

sprawling mal s and shopping centers, lawn service and office temps, rent-a-

maid and rent-a-nurse—these are some of the businesses that have emerged

at the low end of Florida’s recent economy, paralleling but hardly supplant-

ing an older low-paid service economy centered on restaurant staff, hotel

maids, and migrant farmworkers.

A high end of the new service economy has emerged, as wel . In the new

information age, the high-tech and business service economy is no lon-

ger tied to older metropolitan centers of the Northeast or Midwest. With

computer networks and other instantaneous communication, it has been

possible for major corporations—and individuals with a laptop—to relo-

cate to Tampa, Miami, Boca Raton, or Sanibel Island; costs are reduced for

company and employees alike, and al benefit from the low taxes, sunny

climate, and enhanced amenities. Florida’s new economy includes high-

tech and computer companies in the state’s “Silicon Beach” area stretching

along the Atlantic coast north from Miami and in the Cape Canaveral area.

proof

The wondrous technological innovation of the late twentieth century, the

personal computer, was developed at IBM’s massive facility in Boca Raton.

Major international trade and banking operations have clustered in Miami

and Coral Gables since the early 1970s. Miami is scarcely the Hong Kong of

the West, but many business and civic leaders have aspired to enhance south

Florida’s place in the emerging global economy. In the late 1990s and into

the new century, Florida governors invested heavily to bring biotech firms

to the Jupiter Island area. Some critics question the investment and return.

Florida must continue to adjust and cope with the new technologies and

global economic networks that will shape the twenty-first century.

New technologies and economies have helped to create modern Florida,

but issues involving race and immigration have generated a more powerful

impact in shaping national and world images of the state. Florida, in fact,

has had a long and troubled history in the area of race relations. In the past,

the legitimacy of its role as a “real” southern state was the subject of frequent

debate, but the history of race relations in Florida leaves little doubt as to the

answer. Florida’s color line, drawn in exacting constitutional detail and ce-

mented in everyday custom, swept across geographical and time boundar-

ies. Jim Crow practices found easy acceptance even in Florida cities without

Boom, Bust, and Uncertainty: A Social History of Modern Florida · 519

southern-born populations, such as St. Petersburg, Miami, and Palm Beach.

In tourist cities, leaders stressed the importance of maintaining a strict color

line and docile black communities, making sure that blacks would serve but

not be seen. When in Florida, most northerners adapted easily to southern

racial customs and segregation. In Miami, Gainesville, Sarasota, and other

places, some northerners, outraged at the status quo, courageously joined

and led the civil rights movement.

Lynching, of course, loomed as the ultimate test of keeping blacks in

their place. Historical y, white Floridians vigilantly used the noose and the

torch to control economic power and enforce southern customs. Florida,

not Alabama or Mississippi, led the South in lynchings in proportion to

population. Vigilante justice was not confined to Jefferson, Levy, Marion,

or Jackson Counties in rural north Florida; Hernando, Pasco, Citrus, Polk,

Hil sborough, and DeSoto Counties recorded especial y notorious acts of

racial violence. Nor was the violence limited to isolated cases and individ-

ual victims. Attacks on entire black communities took place at Lake City,

Ocoee, and Rosewood between 1912 and 1923. African Americans were not

passive victims; rather, they fought back as at Rosewood, and organized

boycotts of streetcars, as in Jacksonvil e and Pensacola between 1901 and

1905. In some cities, such as Miami and West Palm Beach, they joined Mar-

proof

cus Garvey’s black nationalist Universal Negro Improvement Association

in large numbers. Until the 1940s, pol taxes and white primaries largely

kept them from the voting booth most of the time, but when possible (as

in nonpartisan municipal elections in Miami), blacks turned out in force to

exercise the franchise.

Enforcement of the Florida color line continued forceful y after World

War II. In Miami, over a six-year period beginning in 1946, an active Ku

Klux Klan regularly paraded, burned crosses, torched houses, and dyna-

mited apartment complexes in an effort to keep blacks from moving into

white neighborhoods. In 1951, in the small Brevard County town of Mims,

the Klan dynamited the home of Harry T. Moore, a relentless civil rights

activist and statewide leader of the NAACP, killing him and his wife. Na-

tional magazines published articles in the 1950s with such titles as “The

Truth about the Florida Race Troubles,” “Florida: Dynamite Law Replaces

Lynch Law,” “Bigotry and Bombs in Florida,” and “Bombing in Miami.”9

Big-city police departments in Miami, Tampa, and Jacksonville vigorously

enforced the color line, often violently.

African American activism shaped the civil rights movement in Florida,

even in the 1940s and 1950s before the national freedom struggle took off. A

520 · Raymond A. Mohl and Gary R. Mormino

bus boycott in Tal ahassee in 1956 inspired a wider civil rights movement in

the state capital. Lunch-counter sit-ins led by the Miami branch of CORE in

1959 (a year before the more celebrated sit-ins in Greensboro, North Caro-

lina) ultimately led to the desegregation of Miami’s public accommodations

and schools. But the civil rights movement was accompanied by racial con-

flict in the 1960s and after. Violent police behavior in the ghetto prompted

Miami’s Liberty City riot of 1980, and troubled police-community relations

persisted in Miami and Tampa through the 1980s. Even as Florida became

less southern, traditional patterns of race relations persisted. Urban upris-

ings in late-twentieth-century Miami and St. Petersburg and extensive me-

dia coverage of Florida’s racial conflicts initiated new popular images of the

state. Few were happy with either the broad outlines or the minute details

of that image.

Immigration patterns since the mid-1960s have also dramatical y recast

Florida’s image. The Cuban refugee exodus that began in 1959, episodic but

relentless over time, has brought such tumult and change in south Florida

that words such as “transformative” and “profound” seem inadequate. By

the 1990s, close to 1 million Cuban exiles had made the journey across the

Florida Straits. They and others have transformed Miami into the capital

of the Caribbean and Latin America. The Cubans were fol owed by mas-

proof

sive migrations of Haitians and Nicaraguans and smaller contingents from

virtual y every Caribbean and Latin American nation. These migrations

remade Miami and eventual y al of south Florida. The demographic and

cultural changes have been phenomenal—in 2010, some 1.4 mil ion resi-

dents of Miami-Dade County spoke Spanish, a figure outnumbering Eng-