The Historical David: The Real Life of an Invented Hero (23 page)

Read The Historical David: The Real Life of an Invented Hero Online

Authors: Joel S. Baden

Tags: #History, #Religion, #Non-Fiction, #Biography

In truth, this question is relevant only from a later perspective, when the temple was the center of Israel’s religious existence and David was recognized as the greatest king in Israel’s history. Modern scholars have fallen sway to the same forces, often going to lengths similar to those of the biblical authors to explain why David didn’t build the temple. From the historian’s perspective, the question may be answered relatively simply: David did not build the temple—or, better,

a

temple—because he had no need to do so. He had the ark and an altar, and thus both the enticement for pilgrims and the means by which they could offer their sacrifices. A physical temple was unnecessary, and, what’s more, David may have seen a temple as potentially drawing the revenues from the cult away from the royal court. Without a physical temple, the priesthood in Jerusalem was under David’s control: appointed by him and maintained by him. And, at least according to one passage, David’s own sons served as priests—a common reality in the ancient world but an embarrassment to later biblical texts such as Chronicles, for which the idea of anyone from a nonpriestly lineage serving in the cult was unthinkable.

39

The Jerusalem cult was a family business, and David had no reason to create any structures that might take on a life of their own. The Bible wants us to believe that David would have built the temple if he could have. The real question should not be “Why didn’t David build the temple?” but rather “Why

would

David build a temple?” If David didn’t build the temple, it is because he had no desire to.

Israel’s Neighbors

By inaugurating the Israelite cult in Jerusalem, David accomplished something of lasting value, an achievement that still resonates today. Like the unification of the northern and southern tribes, the establishment of Jerusalem as the religious center of Israel changed the course of history. All of the emotions tied up in the city—from the exilic cry in Psalm 137, “If I forget thee, O Zion,” to the medieval zealotry of the Crusades, all the way to the present conflicts over the status of Jerusalem as a joint Israeli and Palestinian capital—are grounded in David’s vision for his capital. It is tempting to apply our own feelings about Jerusalem back into David’s time, to ascribe to him the passion and the piety that the city inspires in us. The biblical authors themselves succumbed to this temptation. But David acted for far more mundane reasons. The choice of Jerusalem as his capital and the decision to make it a religious center for Israel were primarily political and economic. They were grounded in the realities of David’s seizure of the throne and his need to establish himself and his government in the eyes of a conquered and resentful populace. The results, centuries on, may have benefited the entire nation, but the motivations were self-serving.

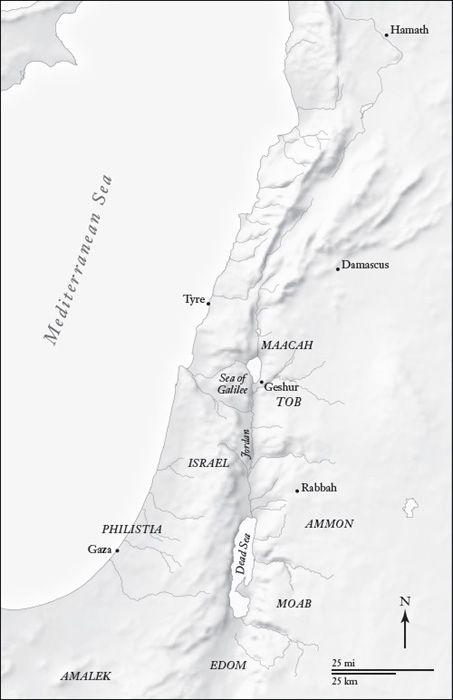

David’s Empire

F

ROM THE CENTER OF

David’s kingdom, Jerusalem, we may look outward to the peripheries. For David is lauded not only for his piety, but also for his military conquests; he is credited with expanding the borders and influence of Israel to virtually all the surrounding nations. David’s kingdom is often described as an empire, collecting tribute from the vanquished foes all around. The biblical claim to such an empire has remained a fundamental aspect of Jewish self-definition for millennia—so much so that when the state of Israel was founded in 1948, it was understood by many that, since David had conquered most of what is now Jordan and Syria, Israel was, in accepting a partition of Palestine that gave it a rather small territory, generously relinquishing its traditional rights to more than half of David’s empire in the name of peace with its neighbors. David’s conquests are an important touchstone for the history of the land of Israel. Yet virtually everything we know about these victories comes from a single chapter in the Bible, 2 Samuel 8. It is our task to evaluate these biblical claims and the picture of David’s kingdom that they present.

40

The first Israelite victory recorded in 2 Samuel 8 is over the Philistines. It is natural enough for the biblical authors to emphasize David’s battles against the Philistines by placing them at the head of the chapter, for victory over Israel’s longtime nemesis was one of the basic rationales for both Saul’s and David’s kingships in the first place. The extent of this victory is ambiguous, however. It is usually assumed that David actually defeated the Philistine heartland along the coast, thereby establishing Israel’s right to that fertile territory—including what we now call the Gaza Strip. The text, however, says only that David attacked “Philistines,” not “

the

Philistines.” It seems that this battle was not a full-fledged assault on the Philistine homeland. Gezer, the Philistine-controlled town closest to Israelite territory, was still in Philistine hands into the reign of Solomon. David never conquered the Philistines in any substantial way. They remained firmly in control of their coastal cities for the duration of his life.

The second verse of 2 Samuel 8 records David’s victory over Moab, the nation across the Jordan to the east of Judah (present-day Jordan). Unlike the long-established Philistine enemy, in David’s time Moab had barely coalesced into a meaningful political entity.

41

It is therefore somewhat unclear what it even would have meant for David to conquer the entire nation of Moab. Then again, the text never quite makes that claim explicitly, though it tries to imply it. On the contrary, just as in the case of the Philistines in the previous verse, the Bible provides no detail whatsoever about the scope of David’s victory. Not a single town or region is mentioned—which strongly suggests that not a single town or region was taken, for the biblical authors would be sure to say so.

42

This may have been a border skirmish, perhaps the result of some small band of Moabites testing the strength of the new kingdom to their west. Regime change was often the occasion for such adventures in the ancient Near East. It was never obvious how powerful a new ruler would be, and thus the rise of a new king often coincided with external attacks or internal revolts.

43

Such may have been the case here, too. Most important, there is no record of Moab having been subjugated by David. In the monumental inscription of the Moabite king Mesha from the end of the ninth century

BCE

, the subjugation of Moab is attributed to the Israelite king Omri, who ruled a century after David.

44

Thus we have here another example of the biblical authors suggesting that David controlled territory that he did not.

From the Philistines in the west and the Moabites in the east, 2 Samuel 8 turns north, to describe David’s defeat of the Arameans led by Hadadezer, the king of Zobah—territory that now belongs to Syria. Here again, however, the text implies more than it proves. The battle described in 2 Samuel 8:3–13 did not take place on Aramean soil, but rather in Ammon, the Transjordanian nation north of Moab. Ammon had been Israel’s enemy during Saul’s reign—in fact, some if not all of Saul’s authority derived from his ability to successfully defend the town of Jabesh-Gilead from the advances of the Ammonite king Nahash (1 Sam. 11). Saul’s enemy, however, was David’s friend: David refers to the fact that Nahash “kept faith” with him, using a technical term for treaty partnership. After the death of Nahash and the rise of his son Hanun to the Ammonite throne, however, David recognized an opportunity to test the limits of his power—again, regime change and international renegotiations went hand in hand. The war against Ammon also served a political purpose for David within Israel. His rejection of his former treaty obligations to Ammon would have been popular with the Israelites, especially those in Gilead, the region most directly threatened by Ammon.

Upon David’s aggression, Ammon turned for help to its allies in Aram, and soldiers came from Zobah, Maacah, and Tob, city-states just to the north of Israelite territory. It is the sequence of battles against these armies, detailed in 2 Samuel 10, that is referred to in 2 Samuel 8 as the defeat of the Arameans. David did not extend Israel’s borders to the north, into Aram—he extended them east, across the Jordan into Ammon. The Arameans he defeated were not even in Aramean territory.

45

There is thus no record of David campaigning in Aram, to the north of Israel. He never occupied Aramean territory—nor does the text ever say that he did. The text implies it, perhaps, but had David really taken this territory, the biblical authors would have proclaimed and celebrated it.

Ammon, on the other hand—the actual object of the battles in which David fought the Arameans—was authentically subjugated. It is striking to note the difference between the reports that imply conquest where there was none and those that describe real conquests. Whereas details of territory taken and cities captured are lacking in those texts that can be classified as exaggerations, the notice of the conquest of Ammon is detailed. “Joab attacked Rabbah of Ammon”—the capital—“and captured the royal city” (2 Sam. 12:26). We cannot find this sort of explicit statement in any other account of David’s conquests, from his early days in Saul’s service to his time on the throne of Israel. This is a factual statement of victory over a foreign capital. It is the only one—and it is therefore the only one that can be trusted. We are further told that David gained possession of the royal crown of Ammon and carried off booty from the city. Moreover, he subjected the inhabitants of Rabbah to forced labor, “with saws, iron threshing boards, and iron axes, or assigned them to brickmaking” (12:31)—and here is where Adoram, who is in charge of forced labor for David, probably made his living, as there is no evidence that David ever subjected Israelites to labor.

46

This description is again in contrast to what we find elsewhere, where references to booty and forced labor are generic at best. When the biblical authors have details to give, they give them—and when they don’t, they don’t.

The last victory mentioned in 2 Samuel 8 is over the Edomites, the nation to the southeast of Israel. Early in its existence, Edom’s territory was confined mostly to the southern Negev, as we know from the biblical story in Numbers 21 of the Israelites’ wandering in the wilderness: they are prevented from moving straight up into Canaan by the Edomites, whose territory they are forced to circumvent.

47

The value of this territory was mostly for its trade routes, which brought rare goods—spices and precious metals—into Israel from Arabia.

48

Although the notice of David’s subjugation of Edom is brief (“He stationed garrisons in Edom—in all of Edom he stationed garrisons—and all the Edomites became vassals of David” [8:14]) it may be trustworthy. Solomon controlled Edomite territory, as he kept his fleet in the Edomite city of Ezion-geber (1 Kings 9:26). But the fact that in Solomon’s time this area was still referred to as Edomite suggests that it was not annexed to Israel, but rather controlled by Israel. It seems most likely, then, that David’s conquest of Edom consisted mostly of his seizure of the southern Negev and the establishment of garrisons to protect the trade route. Remarkably, archaeological evidence supports this process: an unusually high number of settlements in the Negev appeared out of nowhere in the tenth century

BCE

.

49

In 2 Samuel 8, then, we have the biblical argument for the creation of a Davidic empire. The text is arranged geographically, with the conquest of the Philistines to the west, the Moabites to the east, the Arameans to the north, and the Edomites to the south. The artfulness of this construction is telling, especially when we recognize that those in the north, the Arameans, were really defeated in Ammon, to the east. The chapter is not a straightforward historical account, but a piece of propaganda, intended to magnify David’s conquests and give the impression of a mighty empire stretching in all directions. Notably, it appears to be yet another piece of pro-David one-upmanship regarding Saul, for we may note the verse that describes Saul’s military triumphs: “He waged war on every side against all his enemies: against the Moabites, Ammonites, Edomites, the kings of Zobah, and the Philistines, and wherever he turned he worsted them” (1 Sam. 14:47). This is precisely the list of nations we find in 2 Samuel 8, even down to the kings of Zobah. David hardly could be made to seem less powerful than his unworthy predecessor when it came to military success, and 2 Samuel 8 is the biblical authors’ attempt to ensure David’s legacy. Scholars have further argued that this chapter is of a piece with royal propaganda from elsewhere in the Near East, especially monumental inscriptions relating the victories of kings over their many enemies.

50

The text, like its parallels from elsewhere, implies great achievements without quite stating them explicitly. As a piece of propaganda, it has been remarkably successful. Even the later biblical authors of the two books of Chronicles accepted the story as presented here: Chronicles says explicitly that David captured Gath from the Philistines (1 Chron. 18:2), a claim made nowhere in Samuel.