The Hero's Body

Authors: William Giraldi

THE

HERO'S

BODY

William Giraldi

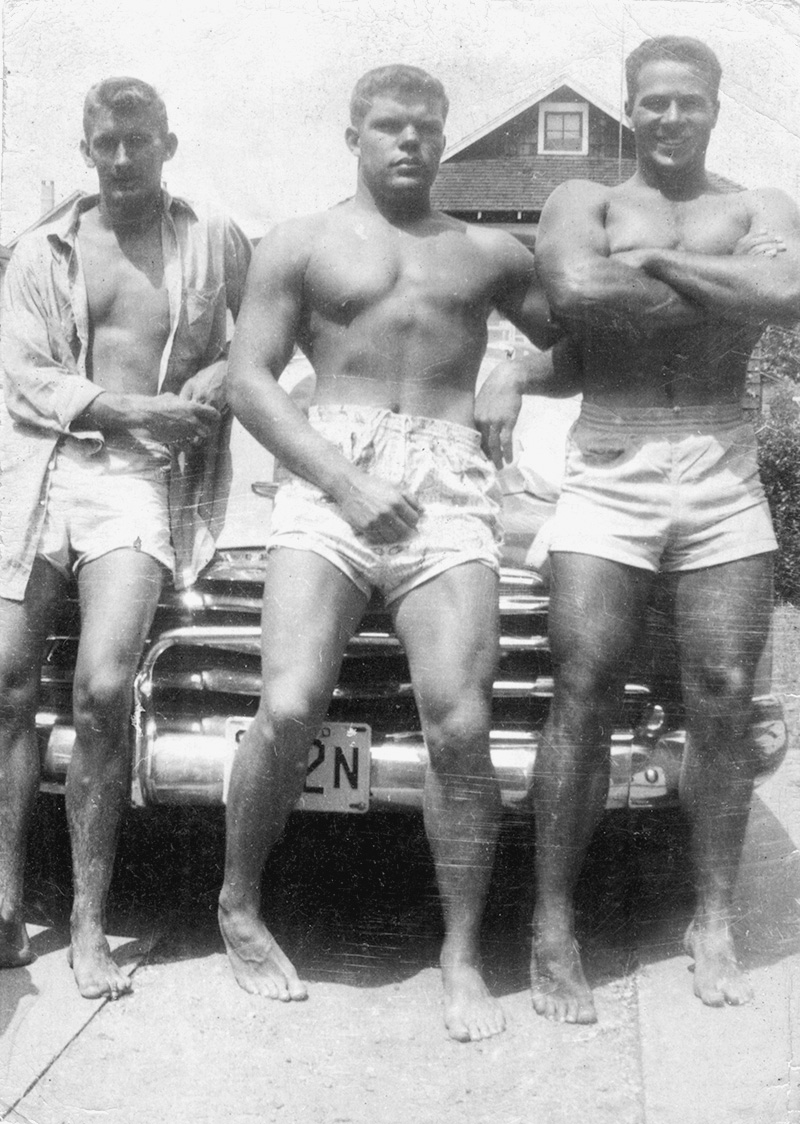

To the memory of my father,

William Giraldi (

1952â2000

),

and to my sons, Ethan, Aiden, and Caleb,

so that they may know him.

THE HERO'S BODY

Prologue    Â

The illness began with

a week of all-around lethargy, how you feel when an influenza first gets into you. Soon the headaches commencedânot the forehead pain you have with dehydration, or a behind-the-eyes throb from reading in muted light, but a panging all along the anterior of my skull. Over the span of several days, the panging migrated into the base of my neck. Then the waves came, whole days of dizziness, followed by a stiffening, a gradual inability to turn my head right or left. A body-wide infection now, something toxic thriving in my blood. About twelve days into this, I blacked out in one of my high school's hallways, slumped against someone's locker. I was fifteen years old that autumn, a sophomore. Friends lifted me from the floor and I woke in the nurse's office, my vision tipped and tinting the world into grays.

Then I was on a bed at my grandparents' house, in a darkened room, unsure how I'd got there or how long it had taken, no longer well enough for fear. A minute or an hour later my father was dashing me across town to a doctor who'd recently opened a private practice. We hadn't had a steady family doctor in years; since my mother had left our family when I was ten, my father, a carpenter, couldn't afford medical coverage. When he carried me into the office that afternoon, a boneless waif over his shoulder, this doctor knew right away what was killing me.

“Meningitis” sounded terminal. The doctor instructed my father to take me

directly

to the hospital, and it was his italicized

directly

that convinced me of my coming doom. He himself would hurry there to perform the spinal tap. I'd once seen a horror movie that had a character infected with meningitis, a wretched young woman, her spine stuck to the outside of her skinâshe looked fossilized. So I'd soon be dying of a slow and grisly

living

decomposition, rabid unto death. Supine and panting in the backseat en route to the hospital, I asked my father, “What's a spinal tap?” He said, “I think they just tap on your spine with a little rubber mallet,” and I didn't realize that he was trying to be funny. Soon I was unconscious again, yet somehow still aware of being suspended in a capsule of fever and hurt.

A spinal tap: a too-large syringe inserted between lumbar vertebrae and into the spinal cord in order to extract the colorless liquid, called cerebrospinal fluid. Meningitis is an infection of that fluid, which causes an inflammation of the membranes, the meninges, that bodyguard the brain and spine. The most common causes are imperial germs called Coxsackie viruses and echoviruses, although herpes and mumps can also bring on the malady. Some of the germs that lead to meningitis can also stir up such infamous problems as tuberculosis and syphilis. Most meningitis targets are children in their first five years of life, but I was fifteenâI could not comprehend what was happening. If you're among the lucky unlucky, you have the viral sort and it will be caught before it causes too much destruction. But if you're among the unlucky unlucky, like the girl in the horror film I remembered, then you have the bacterial sort that isn't caught soon enough and you end up dead.

Here's how a spinal tap happens when your doctor knows what he's doing: You fetal yourself on the table, knees tight up into your chest. The doctor canvasses your lumbar vertebrae for the best place to harpoon you. He then harpoons you and pulls the plunger to

extract the fluid. That's not what happened to me. My doctor-for-a-day pricked and pierced this essential part of me but couldn't extract the fluid. He hadn't told us he was a spinal-tapping virgin, but that's exactly what he was.

I remember looking over at my father, leaned against the heating unit beneath the window, his balding head aslant, his face a mask of stoical consternation, bulky, hirsute arms crossed at his chest in what seemed defiance of this new fact upon me. I imagine he was thinking two things. The second thing was

That looks like it hurts

(and he'd have been right about that), but the first thing was

How am I going to pay for this mess?

It was a good question.

My doctor shot a few more holes into my spine, and that's when my father asked him, “Why won't it work?”

“I . . . don't . . . know,” he said, with those odious pauses between terms.

“You don't know?”

“I just . . . don't . . . know.”

And my father said, “You want me to try it?”

I managed to say no, please, no. He would have handled that needle as if it were a nail, he the hammer, I the lumber. Because he was a master at building things, he sometimes believed he could do anything that took two hands and the right will. His own threshold for suffering was not my own. He had rare use for doctors, hospitals, aspirin. His stomach did, however, keep Rolaids in business in the years after my mother's abandonment: he'd buy the economy bucket of three hundred wafers and finish it in a month.

My doctor at last surrendered and then talked with some hospital personalities about getting an expert to perform the spinal tap. Benumbed and dim-witted, not fully conscious, I remained on the table with the feeling in my teeth of having just chewed tinfoil. And thenâin one hour or two, I couldn't make sense of the clockâin glided the expert. She was a neurologist with the dauntless manner

of someone who knows she's an alloy of brilliance and beauty. Dressed in a plaid skirt, white blouse, and heeled shoes, cocoa hair wrapped up in a fist at the rear of her crown, her complexion like typing paper: just seeing her was enough to let me know that I was about to be resurrected.

My father and my failed doctor stood nearby as this neurologist, with the skill of a master who's long been spinal tapping, drew out the fluid everyone needed to see. The feeling that rippled through me when this life juice left my body? An authentic euphoria: my headache fled, my arthritic neck unloosened, my muddy vision cleared. And I thought three short words:

She fixed me

. It felt like love, like an overdue embrace by the maternal revenant.

I sat up then, as out-and-out amazed as I'd ever been in fifteen years, and I inched off the table, feet timidly finding the floor. I grinned at my father because I thought we'd be returning home now, resuming our lives now. I took a solitary step, and, with that dope's grin still stuck to my mouth, I promptly blacked out in a hump at my father's mud-stippled boots. I'd spend the next two weeks in a hospital bed, everyone vexed as to why my vertigo and murderous head pain would not relent.

I had the viral stamp of meningitis instead of the bacterial, and the doctors insisted this was good newsâgood news that would sentence me to bed as I got more and more waifish, all angles and knots. Each day a retinue of doctors and attendants filed into my room to examine charts and shake their beards and ponytails at me. They took so much of my blood I suspected they were selling it. They wheeled me up and down those antiseptic hallways for PET scans and CAT scans and other scans that showed them nothing, and there was even talk of another spinal tap until I sobbed them out of that plan.

Some pals came to visit, others did not. The news in my high school said that what I had was deadly and contagious both. When I was released two weeks laterâuncured, an enigma stillâmy

father left his construction site at lunch time to pick me up. I was 110 pounds. My spinal column still ached in the places I'd been punctured, and my father, specks of sawdust in his forearm hair, said, “You don't look better even a little.” I wasn't. Another two-week bed sentence awaited me when I got home, and by the time I could stand up without blacking out, it had been more than a month. My grandmother, Parma, was certain that I'd been crippled for life.

After seeing another physician, we were no wiser. Perhaps the persistent vertigo and head pain had been caused by an imbalance of spinal fluid, possibly because my body had been sluggish in producing more after the extraction. Perhaps it was temporary nerve damage from all the freewheeling needlework. Parma felt livid enough to suggest that we sue the doctor, but the suggestion meant little: she knew that my father wasn't the suing kind. When the hospital bills began their monthly assault on our mailbox, they were the new topic of Parma's anxiety. At my grandparents' house, the nightly dinner conversation was usually freighted with dread of one ilk or another. Parma lived in a constant smog of worry that either my siblings or I would be hit with a disease, my father wouldn't be able to pay the bills, the hospital would seize our house, and we'd be living on the corner in a cardboard box with the local hobo. Somewhere in her bustling imagination, Parma believed that there were agents for the hospital who would raid our house and heave us out onto the lawn.

After my meningitis, my father arranged to send the hospital a hundred dollars a month until the hulking sum was paid offâit took seven years. He kept a list of his payments in a black-and-white composition notebook, and, a decade later, after his violent death in a motorcycle crash, I found the notebook in a blue bin and wept with it there on my lap.

BOOK I    Â