The haunted hound; (2 page)

Read The haunted hound; Online

Authors: 1909-1990 Robb White

And he suddenly remembered the man who had bought the place next to theirs. His name was Mr. Worth, and he had a wife but no children. Soon after he came there he had asked Jonathan to go on a coon hunt with him. It ^^'as going to be on Friday night and Mr. Worth said he had some won-

derful coon dogs. But that was the night his mother was thrown by the horse so he didn't go coon hunting.

That was a bad night. Jonathan remembered how quiet everything in the house was; the doctors whispering to each other, his father sitting slumped in the big chair looking at the logs burning in the fireplace. Once, during that long night, Jonathan had heard, far, far away, the cry of the coon dogs.

That was four years ago, when he was nine. Soon after that night they had left the Farm, so that his mother could be closer to hospitals and doctors and things.

Jonathan remembered his mother's face and suddenly put his head down on the desk. She had never looked sad, or unhappy, or afraid. She had never given up hoping that someday she could walk again. But she never did, and when he was a little more than ten years old she couldn't bear to lie there any longer.

Jonathan and his father went back to the Farm only once more. The day after his mother died they drove out there together and, without saying much, picked a lot of flowers from the garden his mother had planted. With them in the back seat of the car they had driven back to town. Jonathan didn't think that his father had ever gone to the Farm again, and neither had he.

He wondered what the Farm looked like now. There wouldn't be much left of it, he guessed. The house and stables and barns would have fallen down by now, he decided. What had become of the hounds and horses? His

father had never said anything about any of them to him. Probably sold them all, or given them away.

The door of the den opened slowly, letting light flood in. Jonathan turned his head and saw Mamie in the door\vay.

''What's the matter, Jonathan?'' she asked, her voice low so Mrs. Johnson couldn't hear.

''Nothing, Mamie."

"No lights and sitting here in the gloominess. WTiat's the matter, boy?"

"Nothing. Really there isn't."

"Just taking a nap?"

"Yes," he said.

"Well, come eat. Just me and you, because Mrs. J. she's gone to her sick sister's or something."

As Jonathan followed Mamie toward the kitchen, he was glad that he wouldn't have to sit across the table from Mrs. Johnson. With Mamie it would be all right.

"Jonathan," Mamie said, her back to him, "no use you thinking about things like that."

"Like what?"

"You know what. You just breaking your heart to do it, Jonathan."

"I couldn't help it, Mamie. It just slipped up on me."

"You be careful then, or you'll end up just like your dad. Haunted all the time by things that are finished and gone. All he's got is a little handful of memories that he holds onto so tight he can't let anything else get in." She turned around and looked at him. "I watch your dad, Jonathan, and to see

him makes something inside me ery just hke a Httle baby. He just killing himself w ith work and worry."

''He's just sort of sad, Mamie.''

''He got to get over that!" she said. "He gof to. What he better do is go back to the Farm to live. That what he ought to do."

"He's going to sell the Farm. That man this afternoon is going to sell it."

Mamie's eyes opened wide. "The Farm? He going to sell the Farm? Oh no, Jonathan. He mustn't do that. You got to stop him from doing that. He got to go baek out there to live. Him and me and you, we all got to go. You got to stop him."

"What ean I do?" Jonathan asked.

"Something! I don't eare what so long as it's something."

Jonathan felt helpless. "There's nothing I ean do, Mamie," he said. "Nothing at all."

CHAPTER TWO

n the morning a shaft of sunhght streaming through the window woke him up. For a while he lay in bed watching specks of dust float in the strong light, then he got up and went to the window. The sky was blue for as far as he could see and with nothing in it except the sun. All outdoors looked warm and good to him. But then, when he looked down into the street far below, the height pressed against his lungs and he felt dizzy.

Outside the door he could hear the vacuum cleaner starting and stopping, starting and stopping. Mrs. Johnson always made Mamie do it that way, because she was one of those people who go around turning off lights and saving electricity.

It would be hard to study with that noise, Jonathan thought, as he got dressed and cleaned his teeth.

He went once again to the window. This time he didn't look down into the valley of the street, but only out toward the far-away woods, bright green now beyond the smoke of the city.

Suddenly Jonathan wanted to get out of this building, get out of the city itself, get out into the green, quiet woods.

And then he knew that he wanted to go onee more to the Farm. For one more warm, soft morning he wanted to wander around in the woods, to see the ponds and the fields again. It wouldn't matter, he deeided, how tumbled down the house was, or how high the weeds were on the lawns, he wanted to go out there.

He came downstairs, and Mrs. Johnson caught him before he got to the door. She made him eat breakfast and then told him to be sure to be on time for lunch.

Somehow to be bossed around by her irritated him. Generally he did what she told him to do and let it go at that. But this morning he resented her. ''I won't be home for lunch at all,'' he told her.

''Where are you going to be, Jonathan?"

"Out," he said. Then he realized that there was no use starting a battle, so he added, ''With Tim Brent. Til eat at his house."

''Has his mother asked you?"

"Of course," Jonathan lied. As he closed the door he wondered why he didn't want to tell her that he was going out to the Farm. He didn't even want Mamie to know.

It was a secret. He could feel himself getting excited as the elevator dropped him swiftly down.

In the lobby he debated as to how to get out to the Farm.

He had enough money to go on the bus but, somehow, he didn't want to go that way. He wanted to be all by himself going out there.

He tried to remember exactly how far it was but couldn't. Ten miles or so, he thought. On his bike it shouldn't take more than an hour and a half, if he pedaled steadily all the way.

His bike was running fine, and it didn't take long to get w^ay out past the railroad shops. He got lost a couple of times but finally found a road sign pointing toward Millers-ville which, he remembered, was the town a few miles beyond the Farm.

The sun was gnawing on the back of his neck by the time he got beyond the city limits. Jonathan wiped the sweat out of his eyes and kept on pedaling, sometimes having to swerve off on the shoulder to keep from being hit by the cars racing past him.

There weren't many houses out here and soon the road was lined with patches of woods on each side.

But it was getting hotter all the time^ and one of his legs felt as though it were turning into solid, aching bone. He began to w^onder whether he had passed the gates of the Farm, but when he saw a brick chimney rising from the long-burned ruins of a house he recognized it and knew that he was still miles away.

The hill was the thing that finally discouraged him. Ahead of him, white and hot in the sun, the highway climbed up a long, steep hill. The hill was so long that the

top of it was invisible in the haze of heat quivering above the road.

Jonathan decided that the best thing to do was to hide his bike in the bushes between the highway and the railroad tracks and then hitchhike a ride the rest of the way. He got off and hid the bike well and then went back to stand beside the road.

Nobody w^ould give him a ride. Drivers just went past pretending that they didn't even see him.

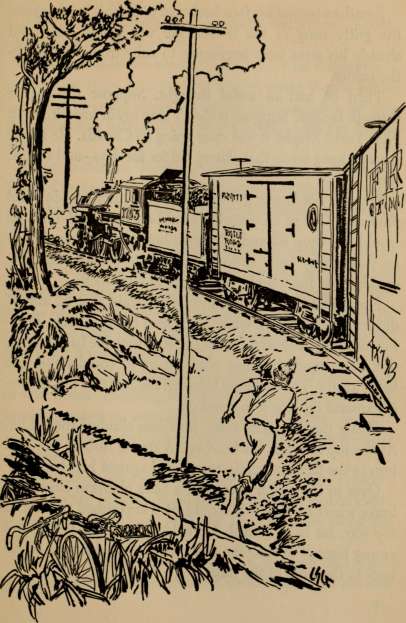

He was getting tired and disgusted by the time he heard the train whistle blow. Soon he could hear the slow panting of the engine.

Jonathan walked over to the tracks and down them. A mile or so away he saw the engine coming with a long line of freight cars strung out behind it.

He decided right then to hitch a ride on the train. With that many cars it would have to be going slow when it hit the hill, so he'd just get on it and ride. The tracks went right past the north pasture at the Farm and when the train got there he'd jump off.

Jonathan had heard of hoboes riding the rods and, though he wasn't sure what the ''rods" were, he was sure that it would be simple to catch a ride.

He climbed down the bank and hid in the bushes where his bike was.

The engine went past him making slow, painful noises. Jonathan watched the man in the cab, but he didn't even look down.

He let four or five cars go by before he sneaked out of the bushes and began to run along beside the end of a boxcar. When he was going fast enough, he reached up and caught the frame of the narrow iron ladder.

It was so easy and neat that Jonathan almost laughed. The movement of the train seemed to help, sweeping him up and swinging him against the car.

Between the two cars there was another ladder going straight up. Jonathan swung himself in between the cars and clung to the ladder. Now no one could see him except from the side of the train.

He felt proud of himself as he hung to the ladder, keeping his head down, for there was a steady rain of cinders falling between the two cars. Looking straight down he could see the shiny-topped track and the crossties flicking by one by one.

The engine got up over the top of the hill—he could tell by the way the crossties began to flick past faster. Finalhv when the whole train was on the downgrade, the ground straight below him was almost blurred, the train went so fast.

Jonathan got scared then. Turning his head slowly and holding on with all his might, he looked out to the side.

He gulped. Bushes and trees flashed by; the sloping graveled right of way ran like a river past the train.

How was he going to get off? Going that fast, if he jumped, the train wouldn't run over him, but he'd break every bone in his body on the gravel.

Jonathan turned his face back and rested his head against the gritty rung of the ladder. He was scared now, and aheady his arms were beginning to ache from hanging to the ladder.

Then he had an awful thought. Suppose this was a through freight? Suppose it didn't stop again until it got to New York? Maybe it was even going to Canada. He might have to hang on to that skinny ladder for days—and nights, too.

Suppose his fingers got numb? Got so they couldn't feel anything? Got so they couldn't hold on anymore? Then he would just drop oflf and fall down between the cars. Down on that silvery track streaming along right under him. He couldn't see the wheels, but he could hear them.

For a little while Jonathan was so afraid that he almost did let go. But after a while he pushed the fear back. Turning his head, he looked over at the coupling. He had thought that there would be some place where he could stand, but there wasn't. The coupling between the two cars was bouncing around too much to stand on.

Slowly then, rung by rung, Jonathan climbed the ladder. At the top he stuck his head up. A strong rush of wind hit him in the face and cinders peppered against his cheeks.

0\'er in the center there was a little platform below the brake wheel on which he could sit. He climbed the rest of the way, his head turned. He held tight to the ladder and swung himself over to the platform and sat down on it, his back to the front of the train.

That was fine. Cinders flew past him and struck his back, but they didn't bother him.

All he had to worry about now was how he was going to get off that train. Maybe, he thought, when it goes across the river, he could climb up on the roof and dive off into the water. But he couldn't remember how high the bridge was.

Then, suddenly, Jonathan remembered the hill at the Farm. The house at the Farm was on top of that hill, and it was a high one. The north pasture was on the side of the hill.

He relaxed. When this freight train got to the hill at the Farm it would have to slow down even slower than it had been going when he got on it. It would be a cinch to get off just as easily as he had gotten on. Just jump off in the direction the train was going and hit running. He might fall down, but it wouldn't hurt him.