The Hare with Amber Eyes (24 page)

Read The Hare with Amber Eyes Online

Authors: Edmund de Waal

How long does this separation of people and where they have lived take? The Dorotheum, Vienna’s auction house, runs one sale after another. Every day there are sales of sequestered property. Every day all these things find people willing to buy them cheap, collectors willing to add to their collections. The sale of the Altmann collection takes five days. It begins on Friday 17th June 1938 at three o’clock, with an English grandfather clock with Westminster chimes. It sells for only thirty reichsmarks. Each day is neatly enumerated to reach an impressive 250 entries.

So this is how it is to be done. It is clear that in the Ostmark, the eastern region of the Reich, objects are now to be handled with care. Every silver candlestick is to be weighed. Every fork and spoon is to be counted. Every vitrine is to be opened. The marks on the base of every porcelain figurine will be noted. A scholarly question mark is to be appended to a description of an Old Master drawing; the dimensions of a picture will be measured correctly. And while this is going on, their erstwhile owners are having their ribs broken and teeth knocked out.

Jews matter less than what they once possessed. It is a trial of how to look after objects properly, care for them and give them a proper German home. It is a trial of how to run a society without Jews. Vienna is once again ‘an experimental station for the end of the world’.

Three days after Viktor and Rudolf come out of prison, the Gestapo assign the family apartment to the Amt für Wildbach-und Lawinenverbauung, the Office for Flood and Avalanche Control. Bedrooms become offices. The grand floor of the Palais, Ignace’s apartment of gold and marble and painted ceilings, is handed over to the Amt Rosenberg, the Office of Alfred Rosenberg, the Plenipotentiary of the Führer for the Supervision of all Intellectual and Ideological Education and Indoctrination in the National Socialist Party.

I picture Rosenberg, slight and well dressed, leaning on the huge Boulle table in Ignace’s salon overlooking the Ring, his papers arrayed in front of him. His office is responsible for coordinating the intellectual direction of the Reich, and there is so much to do. Archaeologists, literary men, scholars all need his imprimatur. It is April and the linden trees are showing their first leaves. Out of the three windows in front of him, across the fresh green canopy, there are swastika flags flying from the university, and from the new flag-pole that has just been erected in front of the Votivkirche.

Rosenberg is installed in his new Viennese office with Ignace’s carefully calibrated hymn to Jewish pride in Zion – his lifetime bet on assimilation – above his head: the grandiose, gilded picture of Esther crowned as Queen of Israel. Above him to his left is the painting of the destruction of the enemies of Zion. But there are to be no Jews in Zionstrasse.

On 25th April there is a ceremonial reopening of the university. Students in lederhosen flank the steps up to the main entrance as Gauleiter Josef Bürckel arrives. A quota system has been introduced. Only 2 per cent of the university students and faculty will be allowed to be Jewish: from now on, Jewish students can only enter with a permit; 153 of the Medical School’s faculty of 197 have been dismissed.

On 26th April Hermann Göring commences his ‘transfer-the-wealth’ campaign. Every Jew with assets of more than 5,000 Reichsmarks is obligated to tell the authorities or be arrested.

The next morning the Gestapo arrive at the Ephrussi Bank. They spend three days looking at the bank’s records. Under the new regulations – regulations that are now thirty-six hours old – the business has to be offered first to any Aryan shareholders. The business also has to be offered at a discount. This means that Herr Steinhausser, Viktor’s colleague for twenty-eight years, is asked if he wants to buy out his Jewish colleagues.

It is only six weeks since the planned plebiscite.

Yes, he says, in a post-war interview on his role at the bank, of course he bought them out. ‘They needed cash for the “Reichsfluchtsteuer”, the Reich flight tax…they offered me their shares urgently, because this was the fastest way to get cash. The price, Ephrussi and Wiener’s price to get out, was “totally appropriate”…it was 508,000 Reichsmarks…plus the 40,000 Aryanisation tax of course.’

So, on 12th August 1938, Ephrussi and Co. is taken off the business register. In the records it says, singularly,

ERASED

. Three months later the name is changed to Bankhaus CA Steinhausser. Under its new name it is revalued, and under its new Gentile ownership is worth six times as much as under Jewish ownership.

There is no longer a Palais Ephrussi and there is no longer an Ephrussi Bank in Vienna. The Ephrussi family has been cleansed from the city.

It is on this visit that I go to the Jewish archive in Vienna, the one seized by Eichmann, to check up on the details of a marriage. I look through a ledger to find Viktor, and there is an official red stamp across his first name. It reads ‘Israel’. An edict decreed that all Jews had to take new names. Someone has gone through every single name in the lists of Viennese Jews and stamped them: ‘Israel’ for the men, ‘Sara’ for the women.

I am wrong. The family is not erased, but written over. And, finally, it is this that makes me cry.

What do Viktor and Emmy and Rudolf need to do to leave the Ostmark of the German Reich? They can queue outside as many embassies or consulates as they like – the answer is the same. Quotas have already been filled. There are enough refugees, émigrés, needy Jews in England to keep the lists closed for years to come. These queues are dangerous because they are patrolled by SS, by local police, by those who might hold a grudge. There is the endless pulse of fear that any of those police trucks could pick you up and take you to Dachau.

They need enough money to pay all the inventive taxes, pay for the many punitive permits to emigrate. They need to have an assets declaration of what they owned on 27th April 1938. This is collected by the Jewish Property Declaration Office. They have to declare all domestic and foreign assets, any real estate, business assets, savings, income, pensions, valuables, art objects. Then they have to go to the Finance Ministry to prove that they do not owe any inheritance or building taxes, and then show evidence of income, commercial turnover and pension.

And so Viktor, seventy-eight years old, begins his tour of historical Vienna, visiting one office after another, rebuffed from one place, unable to get into another, queuing in order to get to offices at which he has to queue again. All the desks in front of which he has to stand, the questions barked at him, the stamp resting on the pad of red ink that allows him to leave or not, and the taxes, edicts and protocols that he needs to understand. It is only six weeks since the

Anschluss

, and with all these new laws and new men behind desks anxious to get noticed, anxious to prove themselves in the Ostmark, it is mayhem.

Eichmann sets up the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in the Aryanised Rothschild palace in Prinz-Eugen-Strasse to process Jews more quickly. He is learning about how to run an organisation efficiently. His superiors are hugely impressed. This new office will show that it is possible to go in with your wealth and citizenship and depart a few hours later with only a permit to leave.

People are becoming the shadow of their documents. They are waiting for their papers to be validated, waiting for letters of support from overseas, waiting for promises of a position. People who are already out of the country are begged for favours, for money, for evidence of kinship, for chimerical ventures, for anything written on any headed paper at all.

On 1st May the nineteen-year-old Rudolf gets permission to emigrate to the US: a friend has secured him a job in the Bertig Bros. cotton company in Paragould, Arkansas. Viktor and Emmy are left alone in the old house. All the servants have now left except Anna. These three people are not moving towards complete stasis: they are there already, frozen. Viktor goes down the unaccustomed steps to the courtyard, passes the statue of Apollo, avoids the looks of the new officials, and the looks of his old tenants, out of the gateway, past the SA guard on duty, onto the Ring. And where can he go?

He cannot go to his café, to his office, to his club, to his cousins. He has no café, no office, no club, no cousins. He cannot sit on a public bench any more: the benches in the park outside the Votivkirche have

Juden verboten

stencilled on them. He cannot go into the Sacher, he cannot go into the Café Griensteidl, he cannot go into the Central, or go to the Prater, or to his bookshop, cannot go to the barber, cannot walk through the park. He cannot go on a tram: Jews and those who look Jewish have been thrown off. He cannot go to the cinema. And he cannot go to the Opera. Even if he could, he would not hear music written by Jews, played by Jews or sung by Jews. No Mahler and no Mendelssohn. Opera has been Aryanised. There are SA men stationed at the end of the tram line at Neuwaldegg to prevent Jews strolling in the Vienna Woods.

Where can he go? How can they get out?

As everyone tries to leave, Elisabeth returns. She has a Dutch passport, a possible shield against her arrest as a Jewish intellectual and undesirable, but this is a remarkably dangerous thing to do. And she is indefatigable: she sorts out permits for her parents, pretends to be a member of the Gestapo to get an interview with one particular official, finds ways to pay the

Reichsflucht

taxes, negotiates with departments. She refuses to be cowed by the language of these new legislators: she is a lawyer and she is going to do this right. You want to be official, I can be official.

Viktor’s passport shows him inching towards departure. On 13th May the stamp

Passinhaber ist Auswanderer

, ‘Passport holder is an emigrant’, is signed by Dr Raffergerst. Five days later, on 18th May, is the stamp

Einmalige Ausreise nach CSR

, ‘good for a single journey’. That night there are reports of German troop movements on the border and a partial mobilisation of the Czechoslovakian army. On 20th May the Nuremberg Laws come into force in Austria. These laws, in existence for three years in Germany, classify Jewishness. If three out of four of your grandparents are Jewish, then you are a Jew. You are not allowed to marry a Gentile, have sex with a Gentile or display the flag of the Reich. You are not allowed to have a Gentile servant under the age of forty-five.

Anna is a middle-aged Gentile servant who has worked for the Jews since she was fourteen, for Emmy and Viktor and their four children. She has to stay in Vienna. She has to find new employers.

On 20th May the Grenzpolizeikommissariat Wien, the border control in Vienna, gives Viktor and Emmy their final clearance.

On the morning of the 21st Elisabeth and her parents go out of the oak door and turn left onto the Ring. They have to go to the station on foot. They each carry a suitcase. The

Neue Freie Presse

reports that the weather is a clement fourteen degrees Celsius. It is a route they have done a thousand times along the Ring. Elisabeth leaves them at the station. She has to return to the children in Switzerland.

When Viktor and Emmy reach the border, it is almost impossible to cross into Czechoslovakia as there are fears of an imminent German invasion. They are detained. ‘Detained’ means that they are taken off the train and kept standing in a waiting-room for hours while telephone calls are made and papers consulted, before they are robbed of 150 Swiss francs and one of their suitcases. Then they are allowed to cross. Later that day Emmy and Viktor arrive at Kövecses.

Kövecses is close to many borders. This has always been one of its attractions, a good meeting point for friends and family from across Europe, a shooting-box, a liberty-hall for writers and musicians.

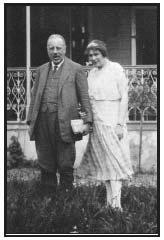

In the summer of 1938 Kövecses looks much the same as it has done, a jumble of grand and informal. You can see the summer storms approaching across the plains, the bands of willows buffeted by the winds on the edge of the river. The roses are more unkempt, in a photo from that month, and Emmy leans into Viktor. It is the only picture I have where they are touching.

Viktor and Emmy at Kövecses, 18th August 1938

The house is much emptier. The four children are dispersed: Elisabeth is in Switzerland, Gisela in Mexico, and Iggie and Rudolf are in America. And you wait for the post each day, wait for a newspaper, wait.

The borders are under review and Czechoslovakia is fissile, and Kövecses is just too close to danger. That summer there is the crisis in the Sudetenland, the area on the western edge of the country: Hitler demands that the German population be allowed to secede to the Reich. There is increasing disruption, the threat of war. In London, Chamberlain attempts to be emollient, to be tactical and to persuade Hitler that his aspirations can be met.

For nine days in July there is an international conference at Evian on the refugee crisis: thirty-two countries, including the United States, meet and fail to pass a resolution condemning Germany. The Swiss police, wishing to stem the influx of refugees from Austria, have asked the German government to introduce a symbol of some kind so that they can identify Jews at border checkpoints. This has been agreed. Jews’ passports are now nullified, must be sent to police stations and will be returned to them stamped with a letter J.

In the early morning of 30th September, Chamberlain, Mussolini and the French Premier Édouard Daladier sign the Munich Accord with Hitler: war has been averted. The lightly shaded areas on the map of Czechoslovakia are to be handed over by 1st October 1938 and the darker areas are to be granted plebiscites. The government in Prague is not present as their country is dismembered. On this day Czech frontier guards leave their posts and Austrian and German refugees are ordered to depart. There are the first Jewish persecutions. There is chaos. Hitler enters the Sudetenland to cheering acclamation two days later. On the 6th there is the formation of a pro-Hitler Slovak government. The new border is just twenty-two miles from the house. On the 10th Germany completes its annexation.

It is only four months since they walked onto the Ring in Vienna to make their way to the station to escape. And now there are German soldiers on every border.

Emmy dies on 12th October.

Neither Elisabeth nor Iggie used the word ‘suicide’ to me, but they both said she could not go on, that she did not want to go any further. She died in the night. Emmy took too many of her heart pills, the ones she kept in the porcelain box of robin’s-egg blue.

In the file of documents is her death certificate, folded into four. A maroon Republic of Czechoslovakia five-krone stamp with a rampant lion is fixed and stamped, though today, the day on which it is filled in, Czechoslovakia no longer exists. On 12th October 1938, it says in Slovak, Emmy Ephrussi von Schey, wife of Viktor Ephrussi, daughter of Paul Schey and Evelina Landauer, died aged fifty-nine. The cause of death was a fault with her heart. It is signed ‘Frederik Skipsa,

matrikár?

’. And there is a handwritten note in the bottom left-hand corner. The deceased was a citizen of the Reich and these records are according to the laws of the Reich.

I think of her suicide. I think that she did not want to be a citizen of the Reich and to live in the Reich. I wonder whether it was too much for Emmy – that beautiful and funny and angry woman – that the one place in her life in which she had been completely free had become another trap.

Elisabeth heard the news in a telegram two days later. Iggie and Rudolf three days after that in America. Emmy was buried in the churchyard of the hamlet near Kövecses. And my great-grandfather Viktor was alone.

I lay out my thin trail of blue letters from 1938 on the long table in my studio. There are eighteen or so, a scant trail across the winter. They are mostly between Elisabeth, her uncle Pips and cousins in Paris, attempting to track where everyone is, how to gain permission for people to leave, suggestions of how to raise money as surety. How could they get Viktor out of Slovakia? All his property had been sequestered and he was stranded in the middle of the countryside, with an Austrian passport that should have been valid until 1940, but now had negligible value as Austria no longer existed as a separate country. As Viktor had been expelled he could not apply at a German consulate for a German passport. He had started to apply for Czech citizenship, but then that country too disappeared. All he had was a document showing him to be a citizen of Vienna and another document concerning his renunciation of Russian citizenship and acquisition of Austrian citizenship in 1911. But that was in the Hapsburg era.

On 7th November a young Jew walked into the German Embassy in Paris and shot a German diplomat, Ernst von Rath. On the 8th collective punishments against the Jews were announced: Jewish children were no longer to attend Aryan schools, Jewish newspapers were banned. On the evening of the 9th von Rath died in Paris. Hitler decided that the spontaneous demonstrations should be unchecked, that the police should be withdrawn.

Kristallnacht is a night of terror: 680 Jews commit suicide in Vienna: twenty-seven are murdered. Synagogues are burnt across Austria and Germany, shops are looted, Jews are beaten and rounded up for prison and the camps.

The letters, flimsy airmail letters, are increasingly desperate. Pips writes from Switzerland, ‘My correspondence has become a kind of clearing-house for friends and relatives who can’t write to one another…I am terribly worried about them as I hear from reliable sources that sooner or later all Jewish men are to be sent to the so-called “preserve” in Poland.’ He begs friends to intercede for Viktor’s admission to England. And Elisabeth writes to the British authorities:

As a result of the radical political changes in Cechoslavaquia, and quite especially in Slovaquia in which his present residence is situated, his situation can no longer be deemed safe. Arbitrary measures against Jews, inhabitants as well as immigrants, have already been taken, and the entire subservience of the country to German domination is sufficient justification for apprehending ‘legal’ measures against Jews in a very short time.

On 1st March 1939 Viktor receives his visa, ‘Good for a Single Journey’, from British passport control in Prague. The same day Elisabeth and the boys leave Switzerland. They take the train to Calais and the ferry to Dover. On 4th March Viktor arrives at Croydon airport, south of London. Elisabeth is there to meet him and takes him to the St Ermin’s Hotel in Madeira Park, Tunbridge Wells, where Henk has booked rooms for them all.