The Gurkha's Daughter (20 page)

Read The Gurkha's Daughter Online

Authors: Prajwal Parajuly

Tags: #FICTION / Short Stories (single author)

“Because we brought them up the right way.”

“Why are you vilifying the poor man?” she asked.

“No, I am not saying he's evil. I think his sons are evil.”

“But maybe the sons want to relieve the father of his burden.”

“And after the father gets rid of their mother, what? Will they ask him to get another wife? Or worse, will they do the same to him when he's sick?”

“I want you to admit me into a nursing home if we come to a situation in which I can't make a decision for myself.”

She didn't care who won the third hand; she had already won the round and wasn't concerned about the bonus that winning all three hands would bring. But she loved beating her husband,

so when she saw her third hand was better than his, she pumped her fist in victory and picked up the two hundred-rupee notes lying by the deck.

“I seriously thought I'd win at least two hands,” he said.

“Give me my

salaami

, too.”

“How about I admit you now?” he said, unsurely handing her another hundred-rupee note. “You're talking like a person who needs to be admitted in an asylum. You deal.”

She went to see Mr. Bhattarai's art one particularly boring Saturday. She'd have called, but she didn't have his number. In an attempt to look a little different, she had tied her hair in a tight bun, saw that it attracted attention to the vermilion in her parting, and then let it loose, like she always did. Her plan was to take the servant's daughter with her, but at the last minute she went alone. Her hand shook when she reached for the bell, and she wondered who would open the door. If it was the wife, it'd be awkward. Thankfully, Mr. Bhattarai appeared, in his hands a copper vase full of orchids.

How fitting that he should pluck the orchids for her home and she was here now, he said. He could have been lying; he had to be lying, but it didn't matter. He was afraid, though, that the quality of orchids this year wasn't as decent as last year's. She looked at the flowers and didn't notice anything lacking, but she was hardly an expert in horticulture. She didn't know he was this interested in plantsâhad he always been? Gardening was his hobby; it was therapeutic. Would she prefer tea or coffee? Water was good, she replied. He would ask the maidâthe robot (ha-ha)âto squeeze some fruit for two glasses of juice. He especially wanted lots of lychees in his drink. Was her retirement any better? She had begun reading Mills & Boon, and it was engrossing. Her husband would hide the books soon because she didn't play cards with him. Going by the way she

was, she'd soon be reading more than she did before the children came along.

She had been to his house before. In fact, she had been subject to an empty trash can flung at her by his wife in the same living room. She noticed a lot of the living room had changed. The glass-topped coffee table was missing. Furniture with sharp edges had been baby-proofed with wads of cloth held together with transparent tape. Yes, that's so Manju doesn't get hurt. Yes, so she doesn't get hurt, she repeated. She looked around to see if she'd catch a glimpse of Mrs. Bhattarai, his Manju. She could have asked him where she was, but she wasn't going to.

He suggested they go to the studio. It was not really a studio, but a part of the guest house converted into his workspace, he added. They left the house from a side door. He stopped midway to get rid of a leech on his calf by using a stray twig for the insect to climb on to. He probably attracted it when plucking the orchids. She thought of proposing they sprinkle salt on the leech to kill it, but when she saw the great care he took to ensure it would escape unharmed, she became ashamed of her thoughts and was glad she made no such suggestion. His calf was red, and she almost touched it. Mother's instinct, she justified her action. Would he need anything for it? Not a thing, please, it happened every day in the garden.

She wasn't much of an artist to judge his work. Besides a pair of paintings of Mount Kanchendzongaâone with the sun rising from its folds, another with clouds concealing a good portion of itâmost of his works were portraits. Several were of his sons at various ages. Had he been painting for a while? No, he had taken up painting only in the last couple of months. He hadn't seen his older son in eight years and his younger one in six. She was afraid she'd have to wait that longâor longerâbefore she saw her children again. He showed her a portrait of his wife. He asked her to observe the eyes, to eliminate the eyes from the

other body parts. She said the eyes alone were eerie. That's how his wife's eyes now lookedâhaunted and suffering, he replied.

They moved to the alcove, where she saw paintings of herselfâone of her running alone, another of her walking pensively, and a third one, her favorite, of her being pulled in different directions by her dogs. Did he go around painting pictures of his fellow joggers? He once painted an old couple that lived by the peepal tree, but when he couldn't get the man's contours right, he gave up. Could she take the painting with the dogs? She would buy it even. Wouldn't her husband mind that her portrait was done by some other man? She hadn't thought of it that way. Well, now was the time to think of it. She looked at him; he looked at her. He'd now show her his best work yetâbut she shouldn't mind, for he was an artist, and artists often did things unacceptable to society. Would she like to see it? Now that she was already here, why not? He unveiled a painting of a woman who looked like her suckling a grown man, who also bore a strong resemblance to herâthe man's mouth obscured her breasts. Her love for her younger son inspired him to paint this “masterpiece,” if you will, he said. It represented motherhood everywhereâthe purest kind of love to exist. The breasts weren't shown because he didn't want the picture to be considered vulgar. She'd have to go. Wait, he shouted. He wanted her to take the orchids home. He had plucked them for her. He meant he had plucked them for her home. She said she understood what he meant and he didn't have to correct himself for the slip. She couldn't carry all the orchids. Would it be all right if the maid brought the bouquet down later? He told her the fruit juice was yet to come. She said she was in a hurry and rushed down the stairs.

The husband recounted the cards and saw the pack was only fifty-one strong.

“I think we are missing a club,” he said. “The jack.”

She took the pack from him and separated the cards by suits into four columns.

“No, it's here,” she said, pointing at a jack of clubs. “It's something else.”

“I am pretty sure we didn't have it yesterday,” the husband said.

“We had it yesterday. I remember getting it way too many times.”

She thought of yesterday and felt a ringing in her ears. The husband got up to look for something and came back with a fading sweetmeat box that contained a motley of cardsâvarious colors, various patterns.

“We probably buy a pack a week,” the husband said. “All right, higher to deal. Maybe we should take up a more constructive hobby, like writing or painting.”

“Let's make a written list of chores.” She felt her eyes lower. “You always lie that we were playing for an easier chore when I win.”

“Nice, positive attitude you're beginning the session with,” the husband said, in his voice a definite undercurrent of sarcasm. “Reading Mills & Boons must have done that for you.”

“Peeling potatoes, refilling supplies, plucking orchids, cleaning the guest room,” she said, noting them down in her curlicue writing. “In that order.”

“Can't the robot pluck the orchids? Didn't we receive some from Mr. Bhattarai as it is?”

“Okay, let's replace orchids with making tea.” Her legs itched.

“May the best man win,” the husband said, turning a queen. “Morning shows the day.”

“As childhood shows the man,” the wife completed his sentence. She picked a five. “All right, you deal.”

The husband was just about done dealing nine cards each when the wife's cell phone beeped somewhere.

“I have to go get that,” she said.

“All right,” said the husband. He smiled a sinister smile.

“Nice tryâlike I will leave you alone with the entire pack of cards.”

“You don't have an option, do you?”

“We need to cancel this round,” the wife said. “I haven't looked at my cards yet, and neither have you.”

She folded her cards and ran to find her cell phone. The beeping had stopped by the time she got to it.

“It's from the US.” She checked to see how many calls she had missed. “Probably Latha. She called once. No, she also called when were at breakfast.”

“I am sure she'll call back again.”

“Probably.” The husband dealt. “We'll call her in the evening. I chatted with Sachin and Rakesh today. Both of them said your idea wasn't so bad after all.”

“How come I always miss their calls?” she said. “What idea?”

“The old-age home.”

“Oh, I had forgotten about it.”

“Their condition was that it would have to be in America.”

“You don't like traveling down to Bagdogra. I am sure an old-age home in America will suit you excellently.”

“But it's Americaâimagine. We can brag to the Bhattarais and the Chettris about living in an old-age home in America.”

You'd have to be a fool not to sense his mockery.

“And we'll reserve a plane so you can travel in peace without your long legs giving you any trouble.”

“You're no fun,” he joked.

“I think it's a stupid idea anyway,” she said.

“What is a stupid idea?”

“Living in an old-age home.”

“I nearly deposited two hundred thousand rupees in Rakesh's account, but then I thought better of it.”

“What made you change your mind?”

“I smother him, you're right. He's no longer a suckling baby. We need to allow him to fly away.”

“I know how you are,” he said with a chuckle. “Now that you have some people agreeing with you, you don't like the idea anymore. Some suggestions you make only to get a rise out of people, don't you?”

“You know me well. After all, we've been married longer than is healthy.”

“Looks like someone's had an overdose of Mills & Boon.”

“I'll get rid of all of them,” she said, as she shuffled the cards. “Their notion of romance is weird. I just don't get it.”

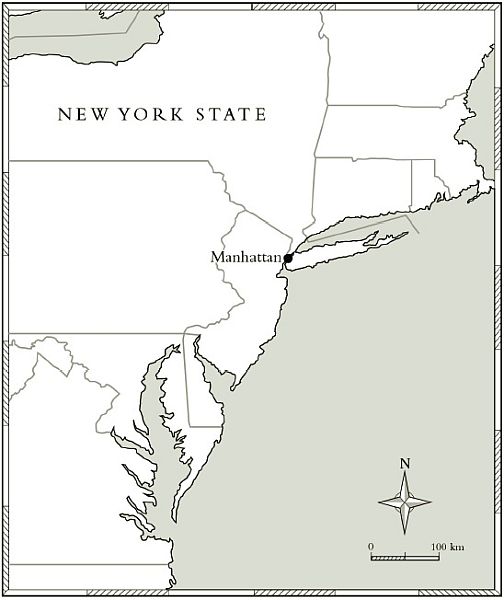

I knew I'd leave the restaurant smelling like spices. Fortunately, I had long ago learned to lessen the pungency of restaurant odors by folding my peacoat into my backpack before I set foot in any South Asian eatery. The waiter, who was also the cook, saw me come in, granted me a simulation of a smile and resumed chopping. Outside the window by my favorite seat, the rains pattered on the Manhattan streets, and a fur-coat-clad elderly woman, classically Upper East Side, caught my eye. She frantically waved for a taxi with her free hand while using the other to control her umbrella, which the wind whipped inside out.

When a particularly strong gust hurled her umbrella halfway down the block, she raised her middle finger. I'd have to help this womanâshe looked fragile and well dressed, and if I stood to gain nothing from this altruistic gesture, I'd at least have spent three precious moments with a rich person, an act that always made me feel wealthy and happy. I asked the waiter-cook to prepare two plates of momos for me and, paying little heed to the pouring sky, stormed out of the restaurant to make a dash for the umbrella. The handle had become separated and was now rolling off into the traffic, so I used the rest of the umbrella to shield myself from the rain as I hastened to the soaked woman.

“Thank you so much, you kind man,” the woman said, hurrying under the umbrella.

“You're welcome,” I replied, displaying my most charming smile. She probably saw a set of uneven yellow teeth, an overbite, and gray dental fillings. “You won't get a cab anytime soon. Perhaps you could wait in the restaurant back there until it stops raining?”

“I don't see why not,” came the unhesitant reply in a clipped accent that evoked New England. Or moneyed New York.

The woman removed her coat upon entering the restaurant, looked around for a hanger, and, finding none, placed it on a chair next to her.

“What a day,” I remarked. It was raining harder.

“I am Anne,” she said.

“Amen is right,” I replied. At first, I mistook her introduction as an “Amen” to my account and was surprised when she extended her hand. Regaining my senses, I said, “I am Amit. What's your name?”

“I am Anne,” she repeated.

“Yes, yes, Anne, you already told me that,” I said, feeling like a fool. “Sorry.”

“No problem, Ahmed . . . right?”

“Amit. A-M-I-T.” It had happened so many times since my move to America that it no longer upset me.

We sat there staring at each other. This was awkward.

“How hungry are you?” I asked.

“Very hungry,” she said. “Do you come here often?”

I did. I came to Café Himalaya a lot. Despite having been away from home for so long, I didn't have a real yearning for it, except when it came to momos, and Café Himalaya was the only place in Manhattan where you could get decent Tibetan dumplings, the closest thing to Darjeeling momos in the city. For months after moving to New York, I found a poor substitute

in Chinatown dim sumsâthe soy sauce just didn't feel right as an accompaniment, and the flour wrapping was disappointingly thick, making the dumplings taste like an amateur attempt at my favorite food. I considered it one of my luckiest days when I walked by this café, so inconspicuously sandwiched between a bar and a Thai restaurant that I would never have noticed it had the larger-than-life portrait of the Dalai Lama on one of its walls not aroused my curiosity. I had returned at least twice a week ever since.

“My favorite is the chicken momo,” I said, pointing at its description on the menu. “I usually eat two plates of themâthey are so good. I've already ordered.”

“Oh, momos,” Anne remarked in delight. “I just ate them last week.”

This was interesting. It's not every day that you came across an American who knew about momos. When I told people I was of Nepalese origin, they instinctively asked me if I had climbed Mount Everest. When I answered no, I hadn't climbed Everest and no, I did not know anyone who had, they were disappointed. When I mentioned I was from Darjeeling, most people asked me a tea question. When I let them know I couldn't distinguish one variety from another and that I didn't drink tea, they looked bewildered. And if I told anyone I was an Indian with Nepalese origins, they looked at me in wide-eyed wonder, sometimes pressing me to volunteer information about this curious mishmash. I wouldn't have minded recounting my family history so much if the inevitable “So, you're half-Nepalese and half-Indian?” question didn't come up. Sometimes I drew a map and went through a spiel on the difference between ethnicity and nationality. Most other times, I just stayed silent and let people continue living in their uninformed bubbles.

“How do you know about them?” I asked, unable to hide my excitement.

“Are you a Nepali?”

“Yes, I am,” I said. “A Nepali from India.”

“Yes, yes, there are a lot of you in India, right? Himachal?”

“No, Darjeeling.”

“Beautiful, beautiful place.” She looked outside. Two teenagers jumped into the slush, drenching passersby.

“Have you been?” I asked.

“These rains must remind you of the place.”

“Yes, it rains a lot. And we get landslides, but it doesn't rain this way in March. It's still very cold.”

“It's cold in New York. It will be cold until the middle of April.”

“So, have you been to Darjeeling?” I asked again. The rains came down like they did in Darjeeling, something that smelled like home spluttered in the kitchen, and the momos would soon be here. A little conversation about all the places in Darjeeling Anne might have visitedâthe Chowrasta, Glenary's, the zoo, and the Ghoom Monasteryâwould be an excellent way to end this dreary day.

“No, I haven't,” she said.

I paused, waiting for her to qualify her answer, but she had nothing to add. I was with the worst conversationalist in the world.

“You seem familiar with it.”

“I am sorry. I was just thinking of someone. No, I haven't been to Darjeeling, but I have a maid who is Nepali. I was just reminded of her. She began working for me recently. She makes good momos. I also read about different places.”

She brought the chopsticks down on a momo and put the entire thing in her mouth, looking like a masticating beast.

“She's a nice girl.” She continued swallowing the dumpling. “Her language is still poor, but she understands me well and gets along well with my grandkids. I'll tell her I met you.”

“Does she live with you?” I asked.

“No, she lives in Queens. Not Jackson Heights. The other neighborhood.”

“I am not very familiar with Queens,” I boasted. I was hoping she'd ask where I lived, but she didn't.

She thought hard. “Sunnyside? No. Woodside, Woodside.” She was on her third momo by now. “These are good. The inside isn't so spicy. I like them better.”

“Yes, we Darjeeling people eat momos slightly different from the ones in Nepal. Our insides are bland. All the spices are in the chutney.”

“I don't like the chutney.” She pronounced it

choot-ney

. “Gives me heartburn.”

“So this girlâyour maidâis she from Kathmandu?”

“Yes, but originally from a village in the hills. She's a nice girl, but communication sometimes is a problem. She's great at what she does.”

“Does she come every day?”

“She's off Saturdays and Tuesdays. I tell her she doesn't have to cook, but she likes the kitchen. And she sometimes makes good stuff. By now she knows I don't like spices so much. I like the way they smell, thoughâraw and fresh.”

Yes, the spices that stink up your apartment, and your clothes and your hair. I didn't want to think of how long the smell of spices from this restaurant would linger on my clothes. No precaution was good enough.

“My maid comes in about twice a week,” I lied. She came every two weeks. “She's very good, but I've always wanted a South Asian maid. I am tired of eating all my threeâwell, I skip breakfastâmeals out. It'd be excellent if someone came in once a week or so and made enough food to last me a couple of days. I'd just need to boil the rice.”

I hoped this scrap of information would impress her. It stunned everyone I met when I said I had a maid. It was like

mentioning my Manhattan apartment, the one I owned and did not rent. Sure, it may have been in the middle of Harlem, the part still not associated with gentrification and urban renewal, and the entire place was the size of my room in Darjeeling. But it was in a nice building, and I knew it was a solid investment.

“Wait, you should hire Sabitri,” Anne said. Clearly, nothing would enthrall this millionaireâneither a twenty-five-year-old owning a piece of Manhattan nor a twenty-five-year-old having a maid. “She keeps trying to tell me she wants more work. None of my friends want to hire her because of language issues. The poor thing has been in America five years, but her English has shown little improvement. She could come to your place on her days off. Maybe you could teach her English.”

I had never looked for a Nepalese maid. I liked my German maid fine. A Pakistani friend and I joked in college about how a brown man's biggest aspiration was to hire white help. Honestly, I was only half joking then; to me, having a white maid was an indication that I had made it. Letting the world know that I had a German maid made me feel smug and superior, not that I would ever admit it to anyone but the Pakistani. It made me feel like I had climbed yet another ladder of success. There you go, Baba, I thought, wasn't it you who discouraged me from going to America and warned I'd have to wash dishes here? All these white people's dishes? This is what I get, Aamaa, when I dream bigger than being an instructor at a college in Darjeeling. Well, here I was, with an apartment and a maid in New Yorkâa white German maid, whom I had no intention of ever getting rid of. The idea of eating home-cooked food every day, however, appealed to me.

“Is she very expensive?” I asked, finishing my momo. A plate was just not enough these days. “I do not want to fire my current maid. I'd have to accommodate both of them.”

“She charges me seventy dollars a day,” Anne said, blowing ripples on the tea that our unsmiling waiter-cook generously

provided us with today. “She needs to subsidize her rate if she wants some English lessons from you.”

“No, no, it's not the money,” I said. “But is she as good as you say she is?”

“Take my word for it. She's excellent.”

“Can you give her my number?” I handed her my card.

The downpour had calmed into a drizzle. The check arrived, and I offered to pay. To my surprise, Anne accepted.

“Do you want to split a cab home?” I asked.

“Where do you live?”

“I just bought an apartment close to Riverside Drive.” I grabbed the opportunity. My apartment was half a dozen blocks away from Riverside Drive, and the area was nothing as nice.

“I live in Gramercy,” she said as we stepped outside. “You'll probably want to take a different one.”

A cab pulled up. I retrieved my coat from my backpack.

“Thanks again for the umbrella and the momos,” she said, not ungraciously. “I'll make sure Sabitri gives you a call.”

To some people, owning a Manhattan apartment in your early twenties with zero help from your parents is just not extraordinary enough.

Sabitri called me at work the next day. I wasn't at my desk because my boss and I were meeting with the human resources director to iron out the details of my application for the H-1B, the visa that would entitle me to work legally in America for another three years. On the expiration of the three-year term, I could get the visa extended for another three, after which I would be eligible for a green card. I had my future in America all mapped out and was excited about the next big step.

The morning's meeting was tedious, but I had been successful in getting the company to pay for the sponsorship, a notion my boss was initially opposed to. Wanting to share the big news

with somebodyâanybodyâI picked up the phone but didn't know whom to call and instead checked my voice mail. A few seconds of static later, a voice said “Hello,” followed it with “

Chee hou

” and a nervous laugh. It had to be Sabitri. I called her back.

“This is Amit,” I said in English. “Anne must have told you to call me.”

“Oh, Madam.” She switched to Nepali. “Yes, I called you today. I didn't know she had given you my number, too.”

“No, no,” I said and then adjusted to Nepali. “I got the number from my phone. She says you're interested in English lessons.”

“Yes, where in Nepal are you from?” she asked. “Madam told me about meeting a Nepali from India. I was a bit confused.” She spoke the kind of antiquated Nepali we in Darjeeling made fun of and associated with poor villagersâher verbs agreed with the gender as well as the status of her subjects, a concept we grasped with great difficulty in school and never really used outside the academic world.