The Guilt of Innocents (2 page)

Read The Guilt of Innocents Online

Authors: Candace Robb

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Historical, #Mystery & Detective, #Crime

1

real historical figure

churching | a woman’s first appearance in church to give thanks after childbirth |

mazer | a large wooden cup or bowl, often highly decorated |

mystery | craft, or trade, particularly used in connection with craft guilds |

pandemain | the finest quality white bread, made from flour sifted two or three times |

scrip | a small bag or wallet |

staithe | a landing-stage or wharf |

toswollen | pregnant |

York, late November 1372

The tavern noises swirled above Drogo’s bent head, but he found them easier to ignore than the constant chatter of his daughters and wife in his tiny home. He loved them more than his life, but when he was home they could not let him rest. After a week piloting ships on the Ouse he was weary to the bone but they thought he was home to make repairs and listen to their tales of woe. So he’d come to the tavern intending to drink himself into a comfortable stupor and then stumble home to pass out, blissfully oblivious to all.

He had just begun his first ale when the man he least wished to see appeared at his table.

‘Behind the tavern,’ was all the man said before turning sharp and walking back out into the chilly afternoon.

Fearing him too much to ignore him, Drogo gulped down what remained in his tankard and

pushed himself from the table, clumsily spilling the drink of the well-dressed man across from him.

‘Watch what you’re doing,’ the man muttered.

Drogo apologised aloud, but beneath his breath he cursed as he walked away. ‘Mewling merchant. Thinks he’s the centre of God’s kingdom on earth. He can afford to spill ale.’

Outside the wind encouraged Drogo to duck quickly into the narrow alley. The overhanging roofs blocked what little light remained in the sky, and Drogo had not yet adjusted to the dark when he felt a sharp blade slice across his cheek. ‘For pity’s sake!’ He flung up his hands to shield himself but too late to prevent another cut, this one on his neck.

‘I warned you what would happen if you crossed me,’ his attacker growled. ‘Thieving and telling tales.’

Another flick of the blade sliced Drogo’s hands.

‘Keep your cursed money!’ Drogo shouted. ‘I wash my hands of you.’

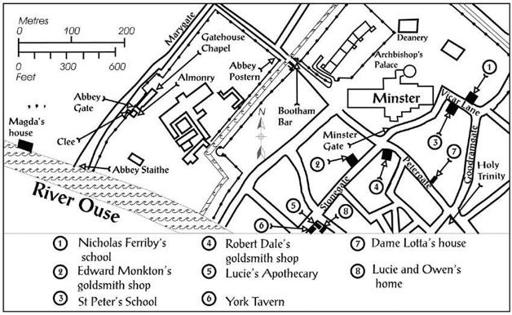

He turned and bolted down Petergate and through Bootham Bar, the streets blessedly empty, not looking back until he stumbled just without the city walls. The bastard was not following. Drogo slowed his pace and hurried on towards the Abbey Staithe and the safety of his fellow bargemen.

‘Dear Lord, I swear I’ll stick to my proper work from now on, I’m a pilot and a bargeman, not a trafficker. I swear.’

T

he Benedictine Abbey of St Mary dominated the northern bank of the River Ouse just upriver from the city of York, and it also owned extensive lands throughout Yorkshire and elsewhere in the realm whose rents and crops supported the community of monks. Its staithe, or dock, at the foot of Marygate served as the hub for moving the abbey’s products, supplies, and personnel, as well as the frequent visitors both clerical and noble. A group of liveried bargemen operated the staithe, chosen for their strength and knowledge of the river and its moods, not for their education or piety.

At St Peter’s School, the song and grammar school of York Minster, Master John de York presided over twelve endowed choristers and at least sixty paying young scholars, many of whom lived in the Clee, a house owned by the minster although attached to the Almonry of St Mary’s Abbey in Marygate, not far from the Abbey

Staithe. The high-spirited boys often tangled with the bargemen. The bargemen taunted the scholars for their privileged lifestyle and useless learning, and the boys retaliated by clambering about the landing place and sometimes onto the barges wreaking innocent havoc. Occasionally, the uneasy relationship erupted into violence …

As was his custom, Jasper de Melton had lingered in the classroom after the lessons ended for the day to copy an additional reading into his precious notebook of old parchment scraps that Captain Archer had bound for him. Master John hummed as he tidied the room, occasionally stealing a peek at Jasper’s work. The grammar master’s interest annoyed Jasper a little because he did not want to feel rushed. He’d make a mistake for sure, tired as he was by this time of day, and he hated scraping and recopying. That would be one less layer for a future reading. He sighed with relief when he came to the end of the brief passage. Even without the master he would have felt the urge to hurry this afternoon, for he wanted to accompany his fellow scholars to the Abbey Staithe.

Frosty air shocked him out of his late afternoon drowsiness as he pushed wide the door of St Peter’s School, and it momentarily killed his enthusiasm for the coming drama, an attempt by his fellows to recover a schoolmate’s scrip, or purse, from a less-than-honest abbey bargeman named Drogo who had just been seen back at the

staithe. Jasper must head to the staithe now if he meant to participate, and then board the barges anchored there. The mere thought made him shrug up his shoulders to protect his neck and ears in anticipation of the cold – it was a week past Martinmas and winter had taken hold. He’d forgotten his cap this morning, and his hands, which stuck out of his sleeves, were already stinging from the icy air. He’d suddenly grown quite a bit. His foster mother Dame Lucie said that it was his recent burst of growth that caused his legs to ache at night, waking him, not unusual at the age of fourteen. A restless night was certainly the cause of his oversleeping this morning and then, in his hurry to be on time, forgetting his cap and gloves.

Jasper was glad to be back at the minster school among his friends – he enjoyed being caught up in the energy that bubbled up to the surface now and then, as it had today when the more senior boys heard that Drogo had been seen at the staithe. Timing was critical because Drogo frequently travelled up and down the Ouse piloting ships between York and the sea, so he might not stay long in the city. The older boys had quickly devised a plan to confront the man about Hubert’s scrip: the main body of scholars were to rush the bargemen and distract them while the older scholars dealt with Drogo.

Jasper wasn’t convinced that Hubert’s absence from school the past week had to do with the

loss of his scrip. That had happened more than a fortnight earlier, and Hubert had attended class for a week afterwards. He knew that the lad had more on his mind than his lost scrip. In the autumn Jasper had come upon him behind the school, all curled into himself and weeping. Jasper had heard that the lad’s father was feared dead. Having lost his own father when younger than Hubert, Jasper understood the fear in the boy’s eyes when he loosened up and began to talk of his mother’s troubles with the farm, how suddenly they were poor. In Jasper’s opinion such a loss and the subsequent fear about the future were more likely to keep Hubert away from the classroom than would the loss of a scrip. Although if it had held money its recovery might comfort the lad a little.

Perhaps that was sufficient reason to help recover it, even though Jasper had promised the captain that he would not get involved in the skirmishes between the scholars and the bargemen. He was still debating whether to follow his fellows or to head straight home to the apothecary. He doubted he would contribute much as he was unfamiliar with the barges, but he knew he’d feel left out when the others talked about it afterwards. He was sympathetic to Hubert’s situation as well.

It was plain that he must quickly choose, for those leading the band of scholars were already out of sight. In fact, the light had faded enough

that Jasper could see only the last few stragglers.

Surely he might be late to the apothecary this one afternoon. He’d been a diligent apprentice the past year, having withdrawn from school the previous autumn when Dame Lucie was injured in a fall and could not spare him from the apothecary – she was his master as well as his adoptive mother. Dame Lucie had regretted cutting short his education, so she’d worked to convince the guild to provide her a second apprentice in order that Jasper might complete his studies. A few months ago Edric had joined the household, an experienced apprentice a few years Jasper’s senior whose master had recently died. Edric could mind the shop.

By now his fellows were out of sight and it was a long way to the staithe – through the minster grounds to Petergate, out Bootham Bar and into the grounds of St Mary’s Abbey by the postern gate, and then out into Marygate and down to the landing. He shut the door behind him and took off into the fading light. Slipping occasionally on frozen mud, Jasper was breathing hard by the time he caught up with the last of the group at Bootham Bar, and his hands and ears were numb. He ignored his physical discomfort as he hurried with them across the abbey grounds, but that was just part of his discomfort now, as he noticed they were being joined by curious onlookers, adults, strangers, not their fellows. He was growing increasingly uneasy about what else

might be happening, about what he might be heading into.

As shouts echoed from the staithe, he and the stragglers ran the last few yards, then slowed upon reaching the barrels and covered flats that had been offloaded from the barges. The long, flat-bottomed vessels were bobbing on the water with the movements of several dozen people darting about, shouting, waving arms. The fading light made it difficult to tell bargemen from the older boys at first, and Jasper thought he’d made a mistake in coming. Glancing around at the gathering crowd he saw fists clenched and heard tension in the voices muttering about privileged scholars and hard-working bargemen, poor lads defending their own and bullying staithe workers. This was growing into something much larger than merely recovering a friend’s purse.

‘How will we know if we come upon the bargeman who took Hubert’s scrip?’ asked one of Jasper’s companions.

He hesitated to respond, considering whether it would not be wise to make a run for home, but he resolved to stay – he was already here, and his reasons for wanting to help Hubert had not changed. ‘Ned said Drogo wears a green cap, has a much broken nose, and a tooth missing up front,’ Jasper said. Ned was one of the raid leaders.

‘Come on, then,’ cried one of the others, grabbing Jasper’s frozen hand.

They’d just stepped onto the nearest barge when

someone crashed into Jasper, and the two went sprawling on the slippery wooden deck.

The human missile groaned as he sat up, rubbing his head. ‘I almost had him!’ It was Ned.

Jasper stood and brushed himself off. ‘Now what?’

Ned had pulled himself up and leaned out over the water to peer at the neighbouring barge. ‘I can’t see him now. I hope one of the others grabbed him. But I tell you, one look in that man’s face and I knew there’d be nothing left of value in that scrip. He has the eyes of a thief, mark me.’