The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March (60 page)

Read The Greatest Traitor: The Life of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March Online

Authors: Ian Mortimer

Tags: #Biography, #England, #Historical

48.

Edward was crowned Vicar of the Holy Roman Empire on 5 September 1338 at Koblenz.

49.

There is no doubt that the two entries relating to William the Welshman’s guardian refer to the same man. In the first he is Francisco Lumbard and in the second Francekino Forcet. Both of these are Italian forms of the Christian name, he is not referred to as ‘Francis’. The second is merely his Italian diminutive. In the first reference his surname refers to his place of origin, which was used while the royal clerk did not know him so well. See Cuttino and Lyman, ‘Where is Edward II?’, p. 530. Although the royal account first calls Francisco Lombard a king’s sergeant-at-arms, this is probably in order to establish his status. He does not appear elsewhere as a member of the English royal household.

50.

The meeting at Koblenz must have taken place in early September; the king then returned to Antwerp by the end of the month. William the Welshman was at Antwerp as his custodian was paid 13s 6d for his expenses for three weeks in December at Antwerp on 18 October. If William the Welshman was not with the king, he did not follow very far behind.

51.

The principal objections to William the Welshman being Edward II, given the likelihood that Edward survived Berkeley Castle, are that the man was ‘in custody’ and that his expenses in Antwerp amounted to so little. This sounds very much like a political prisoner, as Chaplais suggests. However both objections are easily answered: Edward was in the custody of the Genoese, or more particularly Nicholinus de Fieschi. Indeed the testimonial to Nicholinus’s good services the day after Edward III’s coronation may relate to his production of William the Welshman. In other words, Edward II’s status had not changed very much; he was still in custody, brought from Lombardy by Nicholinus de Fieschi. As for the small amount of money for his expenses, Manuele de Fieschi explains this with his reference to the fact that Edward had become a holy man, and lived in a hermitage. He seems to have taken the habit of a monk in Ireland not just to leave Ireland incognito but as a matter of faith. One mark was easily enough for a hermit to live on for three weeks in December, even in Antwerp.

52.

CPR 1338–1340

, p. 190.

53.

CCR 1341–1343

, pp. 83, 182. In addition to his salary on this journey, all his expenses were paid, amounting to more than £86.

54.

Thompson (ed.),

Murimuth

, p. 135.

55.

Gransden,

Historical Writing

, ii, p. 43.

56.

Haines, ‘Afterlife’, p. 75.

Afterword

1.

That Isabella chose to be buried in this dress is suggested on the strength of it being kept for more than fifty years. See Blackley, ‘Isabella and the Cult of the Dead’, p. 26.

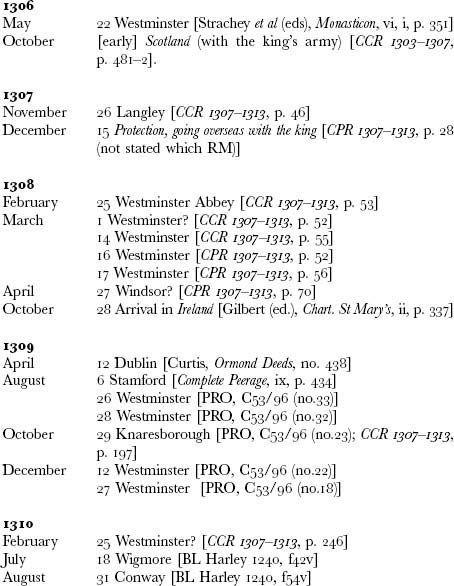

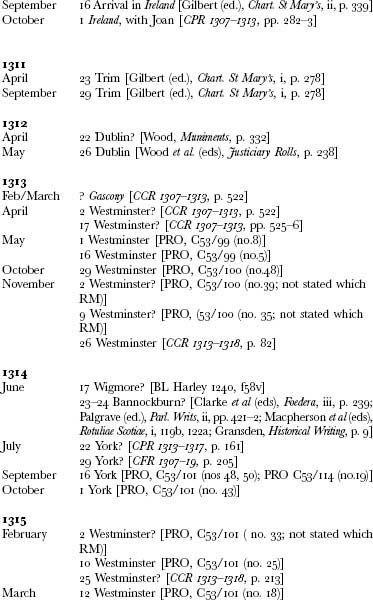

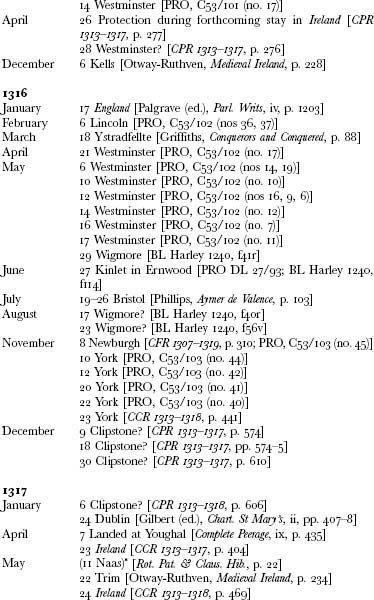

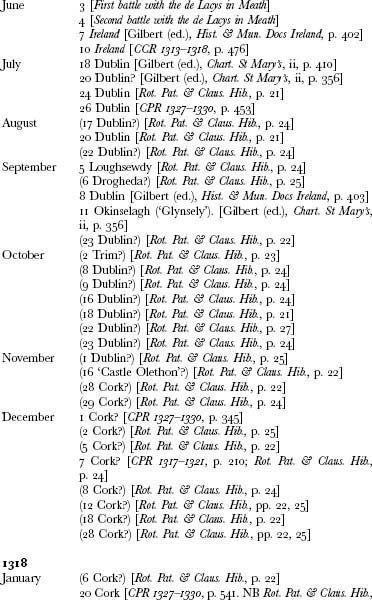

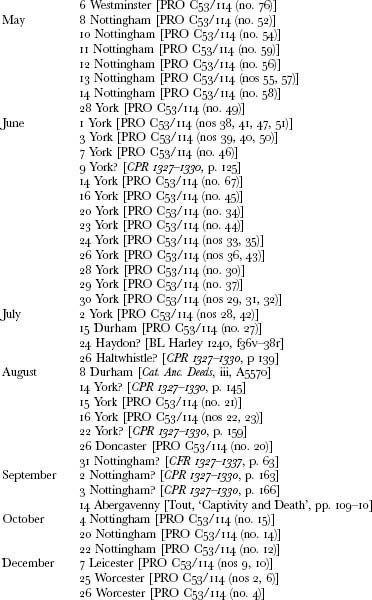

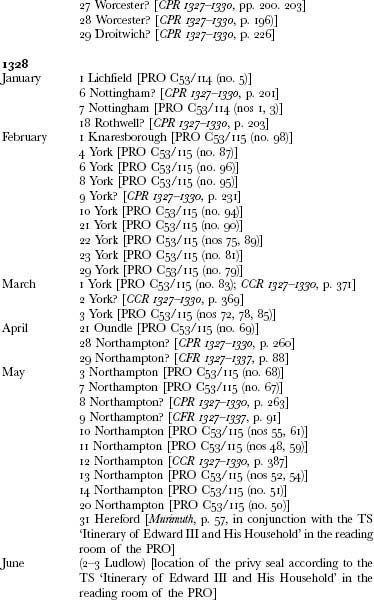

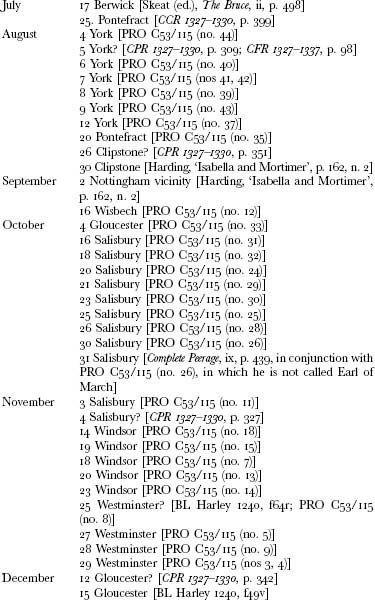

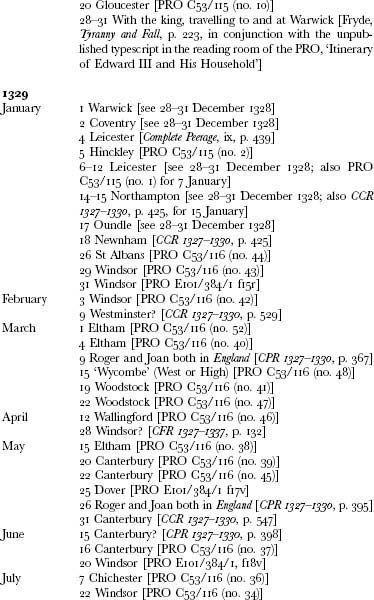

APPENDIX 1

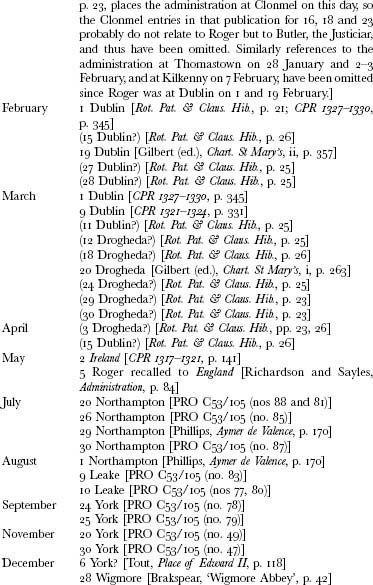

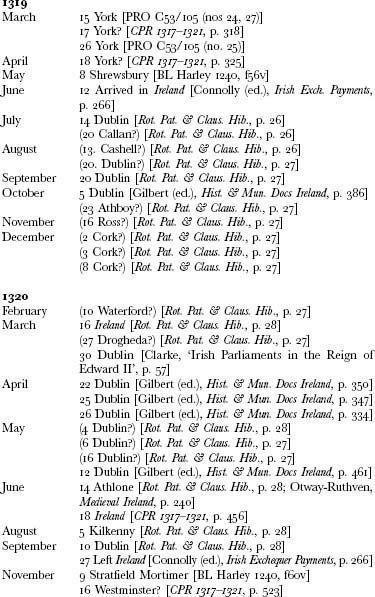

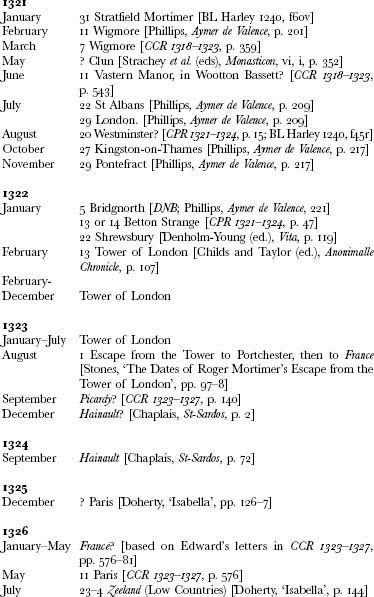

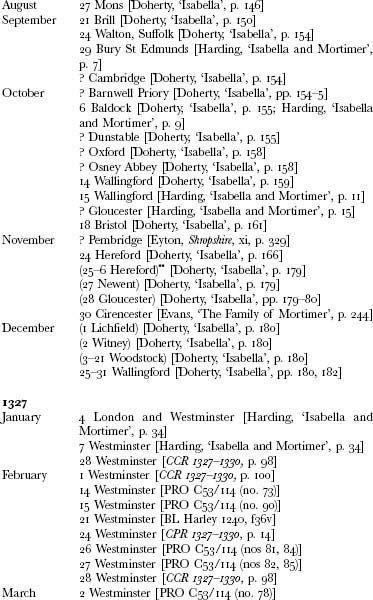

Itinerary of Sir Roger Mortimer, 1306–30