The Great White Bear (13 page)

Read The Great White Bear Online

Authors: Kieran Mulvaney

The meal completed, a polar bear cleans itself. In summer, a thirty-minute meal might be followed by a fifteen- or twenty-minute wash, the bear rinsing and licking its paws and muzzle in a pool of water; in winter, in the absence of liquid water, a bear will rub its head in the snow and roll on its back, doing so repeatedly until the blood, oil, and blubber of its victim are cleansed from its fur and face. Polar bears observe cleanliness to the point of fastidiousness; Richard C. Davids has written that he has "seen them back up to the edge of the ice to defecate in the water."

Having feasted and having cleansed, the bear may pause a while, sniff the air, look around, and amble away. Chances are it will wander up a slope, find a spot sheltered from the wind, make a depression in the snow, and clamber in. And then, as the drifting snow gently covers it up again, the bear will do what many a human will do after a hearty meal: it will curl up and go to sleep.

As the adult bear wanders off in search of repose, our two subadults move in to take advantage of what has been left behind. As they refine their own hunting and survival techniques, they sustain themselves by scavenging the remains of kills made by larger, more experienced bears. They are not exactly starving, not particularly skinny, but they have not broadened out into the healthy, rotund profile of their elders. As Ian Stirling has written, although he has encountered many healthy subadults, he has not come across many fat ones. In those few areas where polar bears and humans overlap, it is almost invariably subadults that become problem bears, skulking around refuse dumps in search of extra nourishment.

Polar bears may take advantage not just of human waste, but of human hunting: in the Beaufort Sea region, and particularly near the village of Kaktovik, dozens of polar bears each year have developed the habit of gathering at the butchering sites of bowhead whales that are killed by Inupiat whalers. "The value of this alternate food is apparently great," notes Steven Amstrup, "as nearly every bear seen near whale carcasses in autumn is obese."

*

But such riches are not available to our two young bears; were they to attempt to partake in such a feast, they would soon be bullied and crowded out of the reckoning by more established bears. Besides, the issue is moot; there is no whaling in Hudson Bay, the frozen surface of which they now prowl. They must instead depend on their own wits and instincts, must build up as much energy and fat deposits as they can during the abundance of spring, to see them through the lean times of summer. And as they learn to hunt, feasting on the scraps from others' tables will help them to do so.

On this occasion they are fortunate. They were the nearest bears to the kill, and their keen noses picked up the scent of the dead seal before any others. Uncertain of their status, not confident in their strength, they did not approach until the bear that had killed the seal had finished and moved away; only when they felt the scene was safe did they move in for the scraps.

An adult bear might not have been so circumspect. The reason why a bearâat the risk of mixing mammalian metaphorsâwolfs down its food is because of the urgency of eating as much as possible before a rival, guided by its tremendously powerful sense of smell, zeroes in on it. In response to the intrusion, the first bear will likely break off from its booty to snarl and threaten the new arrival, but it is rare that two or more bears will come to blows over the carcass of one seal; the chance of one or both animals suffering severe injuries as a result of any fight is too great, and the potential rewardâa part of one seal carcassâis far from sufficient to justify such a risk. It is more likely that after a period of posturing and growling, the rivals will reach an uneasy truce and share what remains before going their separate ways.

Younger, smaller, and less experienced bears are another matter. They have neither the strength nor the confidence to resist any challenges and are frequently driven away from their kills by older, larger, more aggressive animals (and occasionally, although seemingly rarely, may even be killed for their impudence). Even now, as the two subadults chew at the carcass that has been left behind, absorbed in extracting as much nourishment as possible from the remains, they are on the alert for competitors. The wind picks up and the snow begins to swirl, the harsh environment a stark contrast to their formative days in the warmth of the den. Then, life was simple and secure. Now, the world is far more uncertain and intimidating.

Every individual polar bear has what is known as a home range, but such ranges are quite distinct from territories in the more widely understood sense. Whereas brown or black bears may find a patch of land ripe with berries and salmon, claim it, and defend it fiercely, polar bears have no such luxury. Ecological and environmental conditions in the Arctic are unpredictable; the desirability and productivity of one area can change from year to year, month to month, and even week to week. And all the while, the surface on which they walk is constantly moving, shifting beneath themâ"Imagine," says polar bear researcher Geoff York, "living on a treadmill."

While a home range could encompass a great many leads in the ice one year and thus require a bear to cover only a relatively small area, by the following year ice patterns may be completely different. Even in those areas where ice does not melt completely in summer, there will be significant changes from one season to the next. Polar bears' environment is so dynamic that they simply cannot afford the luxury of staking out their own patches, even if those patches weren't constantly moving beneath their paws. Bears go where the climate, environment, and ecology are to their advantage; a bear that has a vast expanse of solid, seal-free ice to itself may be lord of its own substantial domain, but it will soon enough be dead. As a result, polar bears congregate in the most advantageous areas, their home ranges overlapping or even overlaying each other.

That polar bears have home ranges at all is a relatively recent discovery, a consequence primarily of studies involving satellite tracking of bears fitted with radio collars.

*

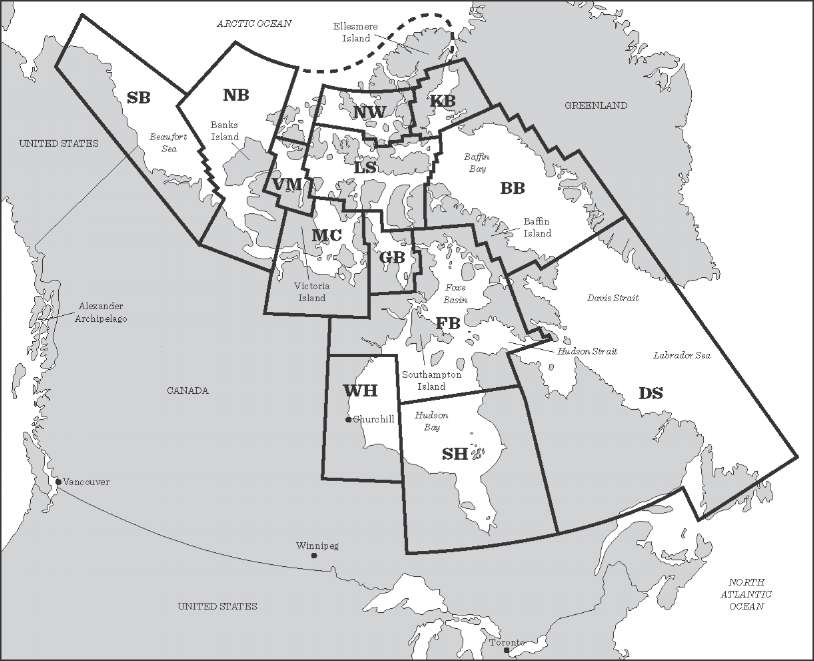

It was long thought that they roamed across the Arctic sea ice, every bear a member of one giant family that knew no limits or boundaries. In fact, not only does each bear largely confine itself to a general range, but the entire global population of polar bears may be divided into a number of discrete subpopulations. Traditionally, polar bears have for management purposes been divided into nineteen subpopulations, thirteen of them in Canadaânine in the central Canadian Arctic, from Hudson Bay in the south to Kane Basin in the north; northern and southern subpopulations in the Beaufort Sea, off western Canada and northern Alaska; and one each in Baffin Bay and the Davis Strait to the east. Delineation of those subpopulations was largely based on bears' fidelity to denning and foraging areas and summer refuges such as the permafrost dens used by bears from Hudson Bay.

But in a 2008 study in the journal

Oryx,

Gregory Thiemann, Andrew Derocher, and Ian Stirling took a closer look and examined Canada's polar bear populations for genetic, geographical, morphological, and ecological similarities and differences. They noted that, for example, Beaufort Sea polar bears tend to be smaller and to reach maturity later than those farther east, and that Banks and Victoria islands act as a barrier between bears from the Beaufort and bears from the central Canadian Arctic. Although the islands of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago serve to separate the bears of that area into six subpopulations, as had long been recognized, Thiemann, Derocher, and Stirling concluded that the separations were relatively weak and the genetic similarities comparatively strong. In contrast, the rugged topography and ice fields of Ellesmere and Devon islands and the thick, relatively seal-free, multiyear sea ice between the Archipelago islands effectively separate the central Canadian Arctic bears from those farther to the north. Contrasting ocean current patterns in Baffin Bay and neighboring Davis Strait mean that, for example, the sea freezes up earlier and breaks up later in the former than in the latter, creating different ecological conditions that have led to genetic differences between the two subpopulations. And the three previously recognized subpopulations of western Hudson Bay, southern Hudson Bay, and Foxe Basin in fact constitute one genetically distinct unit.

Thiemann, Derocher, and Stirling ultimately concluded that there are in fact five "designatable units" of polar bears in Canadaâin the Beaufort Sea, High Arctic, Central Arctic, Davis Strait, and Hudson Bay. Among them, these five units likely contain approximately 60 percent of the world's polar bears.

The 40 percent of non-Canadian polar bears are for now considered to belong to six subpopulations: in East Greenland; the Barents, Kara, Laptev, and Chukchi seas; and, most northerly of all, the Arctic Ocean.

NB

Northern Beaufort Sea;

SB

Southern Beaufort Sea;

VM

Viscount Melville Sound;

LS

Lancaster Sound;

MC

M'Clintock Channel;

GB

Gulf of Boothia;

NW

Norwegian Bay;

KB

Kane Basin;

BB

Baffin Bay;

FB

Foxe Basin;

WH

Western Hudson Bay;

SH

Southern Hudson Bay;

DS

Davis Strait

NB

Northern Beaufort Sea;

SB

Southern Beaufort Sea;

VM

Viscount Melville Sound;

LS

Lancaster Sound;

MC

M'Clintock Channel;

GB

Gulf of Boothia;

NW

Norwegian Bay;

KB

Kane Basin;

BB

Baffin Bay;

FB

Foxe Basin;

WH

Western Hudson Bay;

SH

Southern Hudson Bay;

DS

Davis Strait;

AB

Arctic Basin;

EG

East Greenland;

BS

Barents Sea;

KS

Kara Sea;

LPS

Lapteov Sea;

CS

Chukchi Sea

The ice in the high latitudes of the Arctic Ocean is generally, although not constantly, thicker and less fissured than that near the coasts, and seals are more disparate and harder to encounter. Not without reason is the region decried as the "polar desert." Ralph Plaisted, who in 1968 became the first person incontrovertibly to reach the North Pole, remarked of the area that it was "absolutely desolate." But, he remarked, "we saw fox tracks every day. The foxes follow the polar bears to feed on carrion they leave behind." What he could not understand, however, was the fact that, for all the tracks he spied, he "never saw a fox or one single bear."

For some considerable time, there was uncertainty over whether polar bears seen in the Arctic Ocean basin were truly part of a subpopulation or whether they were merely visitors, extending their range temporarily in search of food. But some of those bears would have to be extending their range very far.

In October 2003, the nuclear-powered submarine USS

Honolulu

broke through the ice 280 miles from the North Pole, where it was promptly investigated by a female bear and two adolescent cubs. At least those bears only looked. Six months earlier, an officer on board the USS

Connecticut

began scanning the immediate area after that submarine also surfaced through the pack ice, only to see a polar bear stalking the vessel and then chewing on and swatting the tail rudder. Damage to the sub was reported to be minor: "Rear rudders of U.S. submarines aren't designed as snacks," said a naval officer.

During their 2005 attempt to cross the Arctic Ocean in summer, Eric Larsen and Lonnie Dupre were bedeviled by the attentions of polar bears in the broken coastal pack off Siberia. During a second attempt the following year, they saw no bears at allâuntil, amazingly, they were at the North Pole.