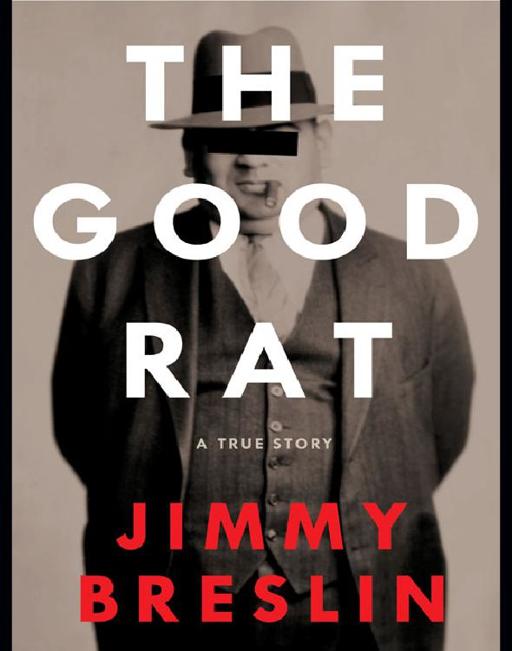

The Good Rat

Authors: Jimmy Breslin

A True Story

FOR SHEILA SMITH

What I’m doing, I’m kissing the mirror, and I’m doing…

He cannot believe that he is doing this, that he…

I can barely handle legitimate people. They all proclaim immaculate…

Even before Burt Kaplan takes the stand, the trial has…

Without Burt Kaplan they couldn’t convict the cops for illegal…

There had been so many years when it was so…

I keep hearing people talk about the end of the…

Even his friend Burt Kaplan described Anthony Casso as a…

I have good reason to remember the period in Brooklyn…

The figure of $35,000 mentioned here was what Casso and…

Eppolito, big, brazen, and brawling, and Caracappa, slender, stealthy, silent-each…

In 2004, two years before Burt Kaplan took over this…

Had you caught snatches of their shoptalk, you would have…

The horse came into the bar after work and had…

It is tempting to see the cops as the evil…

She didn’t know who he was, and therefore we cannot…

In my years in the newspaper business, the Mafia comes…

In court, Burt Kaplan says to the prosecutor, “I could…

This development came in the early nineties, after Burt Kaplan…

On a day in June 2005, Sammy the Bull Gravano…

Liz Hydell, Jimmy’s sister, found out during the trial that…

Later, I am in another courtroom in Manhattan, one with…

As I told Steve Caracappa the night I left to…

FEDERAL COURT JUDGE JACK B. WEINSTEIN,

a master of his trade.

BURTON KAPLAN

, the witness. Read and remember him.

LOU EPPOLITO,

one of the cops Kaplan happened to mention.

STEPHEN CARACAPPA,

also drew some discussion.

ANTHONY “GASPIPE” CASSO,

described as a homicidal maniac. Beyond that, he has a bad reputation.

MITRA HORMOZI, ROBERT HENOCH,

Assistant U.S. Attorneys.

BRUCE CUTLER, EDWARD HAYES, BETTINA SCHEIN,

defense attorneys.

JUDGE DEBORAH KAPLAN,

Burt’s daughter. A New York State Supreme Court judge.

THE INCARCERATED

They are proof that the Mafia is law-abiding. They always go to prison.

JOE MASSINO

GEORGE ZAPPOLA

CHRISTY “TICK” FURNARI

TONY CAFÉ

PETER GOTTI

SAMMY GRAVANO

THE DECEASED

ANNETTE DIBIASE

ISRAEL GREENWALD

JOHN OTTO HEIDEL

JAMES BISHOP

MIKE SALERNO

EDDIE LINO

GOOD NICKY GUIDO

JAMES HYDELL

JAMES HYDELL’S DOG

JOEY GALLO

JOEY GALLO’S LION

LARRY GALLO

BIG MAMA GALLO

PAUL CASTELLANO

JOHN GOTTI

FRANK SANTORA

ANTHONY DILAPI

BRUNO FACCIOLA

JIMMY “THE CLAM” EPPOLITO

JIM-JIM, HIS SON

ALIVE AND FREE AS OF THIS WRITING

SAL REALE

BAD NICKY GUIDO

What I’m doing, I’m kissing the mirror, and I’m doing it so I can see myself kissing and get it exactly right, no tongue and no fucking slop. This way I can go into the clubhouse and kiss them on the cheeks the way I’m supposed to. That’s the Mafia. We kiss hello. We don’t shake hands. We kiss.

I am at the mirror because I’m afraid of lousing up on kissing. When you kiss a guy and he gives you a kiss back, you make sure that your kissing comes across as Mafia, not faggot. That’s why I’m practicing in front of the mirror.

This is real Mafia. For years cops and newspaper reporters glorified the swearing-in ceremony with the needle and the holy picture in flames and the old guy asking the new guy questions, like they all knew so much. The whole thing added up to zero. The kissing is different. It comes from strength and meaning. If you kiss, it is a real sign that you’re in the outfit. You see a man at the bar, you kiss him. You meet people anyplace, you kiss them. Like a man. It doesn’t matter who sees you. They’re supposed to see.

It all started when John “Sonny” Franzese and Joey Brancato, both big guys in the Colombo outfit, bumped into each other one day on the corner of Lorimer Street and

Metropolitan Avenue in Greenpoint, which is in Brooklyn, and they kissed each other on the cheeks. The only thing anybody on Metropolitan Avenue knew was that they had never seen it done before. The moment the men kissed, it became a street rule. This was at least fifty years ago. Immediately they were doing it on 101st Avenue in Ozone Park and Cross Bay Boulevard in Howard Beach. Soon even legitimate citizens were doing it.

Sonny Franzese was born in Italy, brought here by his family when he was two. The family settled on Lorimer Street, which is made of two-story frame houses, home built, and a bakery and restaurant. At a young age, Sonny failed to behave. In school he also fell short. Even in the army for a brief time, he received a poor report card. He sparkled on local police reports and his name got stars on FBI sheets.

The feds soon realized all they had to do was follow guys who kiss each other and they’d know the whole Mafia. Still nobody stopped.

Some guys said that Sonny Franzese had nothing to do with it. “Italian men always kiss,” they claimed. But my friend Anthony—Tony Café—who is the boss of Metropolitan Avenue, says that when Sonny Franzese and Joey Brancato kissed it was the start of a great way for tough guys to know each other. It’s like a password, only it’s more personal.

The only thing anybody can agree on is the clout the old Black Hand had for a while. It came from the smallest

villages in Sicily, where people in need of a favor or a goat went to the village priest for help. They would kiss his hand. Over the centuries Sicily was raided and raped by many other countries. They raided and raped and afterward went into blacksmith shops and stuck their hands into cans of black paint, then slapped the walls outside to frighten anybody who passed. The Sicilians soon took over and began sending extortion notes decorated with black hands and demands for money from the immigrants crowding into downtown New York. Pay or Die. Many paid.

The thing worked for a long time. Maybe we are talking about 1960, when I was in the village of Lercara Friddi, in the hills outside of Palermo, on a day of frigid rain. I was in the vestibule of the local church, large and leaky and falling down. I asked a man for the name of the church and he said, “Church? This is a cathedral.”

Outside in the narrow alley was a cow. The street of low stone houses ended at a field where narrow-gauge rail tracks led into a deserted sulfur mine. Kids in short pants and bare legs huddled in doorways and played cards.

The next morning, on the way to the airport, I found an Italian-English dictionary that I used to buy a stamp pad. I got a handful of postcards and stood off to the side of the ticket counter and smacked my hand on the ink pad and then on one of the postcards. I did this several times. The ticket clerk, pretty and bright as you want, walked over frowning.

“I need you,” I said. “I want to write a thing in Italian.”

“What?”

“Put down ‘Pay or Die’ in Italian.”

She sighed. “Do you really want such silliness?”

I told her sure, that’s what I want, and she made a face and told me again how silly it was. Then she told me to put down

“Paghi o Mori.”

She said, “That is the Sicilian.”

I took those cards and put stamps on them and mailed them to several people I knew back home in New York. The postcards fell on Queens in an attack so sudden and surprising that people’s legs gave out as they read. Dr. Philip Lambert, a dentist who ran a fixed dice game in his waiting room on Jamaica Avenue, was shaking as he showed the card to the veteran cheat Nicky the Snake.

“Look at this,” the Snake said, “it’s from Palermo. Doc, it’s real. What did you do to them? Nobody here is heavy enough to make them go away.”

The doc tried. He took the postcard to Joe Massino of the Bonanno mob. Joe looked at it and frowned.

“One guy can help you,” he said. “God.”

From then on, Doc Lambert lived a life of noisy desperation. He went to the Queens travel agency favored by Sicilians and got people to carry notes to Palermo and give them to taxi drivers. The notes begged the Black Hand to let him live. This made him different from the others who received postcards and writhed in silent fear. When a mob

ster from the neighborhood was killed, the postcard holders believed the Black Hand had struck. Doc Lambert took nervous breaths as he drilled teeth and hoped that he didn’t slip and go through the guy’s tongue. He also hoped to go on living. As far as I know he died of natural causes.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

U.S. Courthouse

Brooklyn, New York

March 14, 2006

10:00

A.M.

CR-05-0192

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

v.

STEPHEN CARACAPPA and

LOUIS EPPOLITO

Defendants

BEFORE THE HONORABLE JACK B. WEINSTEIN

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE, and a jury.

APPEARANCES:

For the Government:

ROSLYNN R. MAUSKOPF

U.S. Attorney

By: ROBERT HENOCH

MITRA HORMOZI

DANIEL WENNER

Assistant U.S. Attorneys

One Pierrepont Plaza

Brooklyn, New York 11201

For the Defendants:

EDWARD WALTER HAYES, ESQ.

RAE DOWNES KOSHETZ, ESQ.

For Defendant Caracappa

BRUCE CUTLER, ESQ.

BETTINA SCHEIN, ESQ.

For Defendant Eppolito

(Open court-case called.)

THE COURT:

Good morning everyone. Sit down, please.

THE UNITED STATES CALLS BURTON KAPLAN.

THE CLERK:

Stand and raise your right hand.

Do you swear or affirm to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth under penalty of perjury?

THE WITNESS:

I do.

THE CLERK:

Your full name, sir.

THE WITNESS:

Burton Kaplan.

DIRECT EXAMINATION OF KAPLAN BY ASSISTANT U.S. ATTORNEY HENOCH.

- Q:

How old are you, sir? - A:

Seventy-two. - Q:

Are you currently incarcerated? - A:

Yes. - Q:

Sir, I would like to ask you to look around the courtroom, specifically at this table, and tell the jury if there is anybody sitting there that you recognize. - A:

Yes. - Q:

Can you tell the jury who you recognize? - A:

Louis Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa. - Q:

Can you please for the record point out an article of clothing that Mr. Eppolito is wearing? - A:

Gray suit with a light tie. - Q:

What about Mr. Caracappa? - A:

Dark suit. - Q:

Did you have a business relationship with Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa? - A:

Yes. - Q:

Can you please tell the jury what the nature of that business relationship was? - A:

They were detectives on the New York Police Department who brought me information about wiretaps, phone taps, informants, ongoing investigations, and imminent arrests and murders. They did murders and kidnapping for us. - Q:

What did you do for them in exchange for this? - A:

I paid them.

He cannot believe that he is doing this, that he is sitting on a witness stand to tell of a life of depravity without end. Burton Kaplan looks like a businessman in the noon swarm of Manhattan’s garment center: an old man with a high forehead and glasses, in a dark suit and white shirt. His face and voice show no emotion, other than a few instances of irritation when one of the lawyers asks something he knows and they do not. “You are wrong, Counselor,” he snaps. His eyes seem to blink a lot, but his words do not.

“Are you a member of the Mafia?” he is asked.

“No, I can’t be a member. I’m Jewish.”

Jerry Shargel, Kaplan’s lawyer for years, says, “Bertie looks like a guy who is standing outside his temple waiting for an aliyah.” An honorary role in the service.

Kaplan’s face has no lines of the moment, the voice is bare of emotion, with no modulation, as if a carpenter makes level each sentence. He does not differentiate between telling of a daughter’s wedding reception and of an attempt to bury a body in ground frozen white in a Connecticut winter. It was bad enough that he had to drive alone with the body in the trunk and on a night so frigid that he shook with the cold. He finally tossed the body through the ice and into the nearest river.

Burton Kaplan brought that ice into the courtroom. Right away I see this old icehouse on the corner of 101st Avenue in Ozone Park. The guy on the platform pulls the burlap cover from a frozen block and with an ice pick scratches the outline of the fifteen-cent piece I am there to get. He stabs the ice and first there is a crack that looks like a small wave and then the block explodes into white. One tug and the fifteen-cent piece goes on your shoulder for carrying to the icebox on the back porch. And now I have a name for Kaplan. “Icebox.”

This suggests that he has bodies on hooks in a freezer somewhere. Close enough. Ask Burt Kaplan a question on the stand and he draws an outline in the ice, and then he answers and there is the explosion. The fifteen-cent piece

separates from the block, and Burt Kaplan comes out of the cold with stories that kill. Yes, they did murder Eddie Lino. Caracappa did the firing. Yes, poor young honest Nicky Guido got killed by mistake. Gaspipe Casso wouldn’t pay any extra money to find the right guy. Kaplan has a morgue full of answers.

He does not come out of a hovel where tough guys, as they are called, are raised three and four in one bed in a wretched family and dinner is anything stolen. He was raised on Vanderbilt Avenue in Brooklyn, a street of neat two- and three-story attached houses with stores on the first floor. Everybody had a job. Kaplan’s father was an electrician. The family had an appliance store and a liquor store. He went to one of the best public high schools in North America, Brooklyn Technical, and, in what often seemed to be the story of his life, he stayed there for a year and a half and was so close to legitimate success when he quit. Of Brooklyn Tech, he laments, “I wish I stood there.”

Instead, he was a great merchant, too great, and after he sold everything that did belong to him, he sold things that did not. As there were no thrills in constant legitimacy, he loved thievery. This resulted in him moving up from Vanderbilt Avenue at age thirty-nine to Lewisburg Penitentiary on his first sentence, four years, federal.

Today, at seventy-two, he still owes eighteen years to the penitentiary on drug charges, and he is in court to talk his way out of them.

We are in a room that is the setting for what is sup

posed to be the first great mob trial of the century, that of the murderous Mafia Cops, Louis Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa. They were detectives in Brooklyn who sold confidential information and murdered for the Mafia. Burton Kaplan was their handler for the Lucchese organized-crime family.

I was hesitant about this trial from the start. These criminals held their secret meetings at a bar next to a golf course. If you look at how mobsters live today, you would say middle class and be right. The late, great Queens defense attorney Klein the Lawyer once said on behalf of some beast, “How could he commit a crime? He lives in a house.” Middle class drowns excitement wherever you run into it. And the idea of cops who use their badges to murder depresses me. It is dreary and charmless and lacks finesse. It promises no opportunity to marvel, much less laugh.

I am at an early hearing when the defendants come into the courtroom, Eppolito fat and sad-eyed, Caracappa a thin, listless nobody. I stare at my hands. Am I going to write seventy thousand words about these two? Rather I lay brick.

Then the trial starts and I am pulled out of my gloom. An unknown name on the prosecution witness list, an old drug peddler, a lifelong fence, steals the show and turns the proceeding into something that thrills: the autobiography of Burton Kaplan, criminal. Right away I think, Fuck these cops. I have found my book.