The Giza Power Plant (6 page)

The shaft, or "well," leading from the N. end of the gallery down to the subterranean parts, was either not contemplated at first, or else was forgotten in the course of building; the proof of this is that it has been cut through the masonry after the courses were completed. On examining the shaft, it is found to be irregularly tortuous through the masonry, and without any arrangement of the blocks to suit it; while in more than one place a corner of a block may be seen left in the

irregular curved side of the shaft, all the rest of the block having disappeared in cutting the shaft. This is a conclusive point since it would never have been so built at first. A similar feature is at the mouth of the passage, in the gallery. Here the sides of the mouth are very well cut, quite as good work as the dressing of the gallery walls; but on the S. side there is a vertical joint in the gallery side, only 5.3 inches from the mouth. Now, great care is always taken in the Pyramid to put large stones at a corner, and it is quite inconceivable that a Pyramid builder would put a mere slip 5.3 thick beside the opening to a passage. It evidently shows that the passage mouth was cut out after the building was finished in that part. It is clear then, that the whole of this shaft is an additional feature to the first

plan.

7

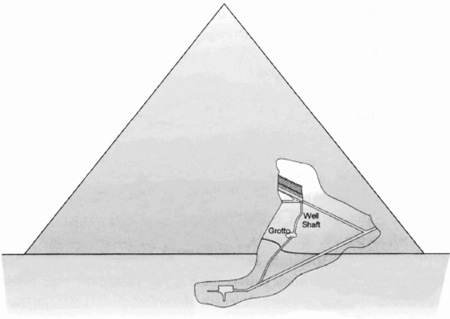

Petrie also noted a large block of granite at the level of the Grotto. The block was positioned as though it had been pushed aside from the vertical section of the shaft. What was this block of granite doing down a shaft, which, in many minds, had nothing to do with the original design of the pyramid?

After tunneling through virgin rock and reaching the level of the Grand Gallery, why would anybody decide to drop a block of granite down the Well? This would take considerable effort. And where did they get the granite? There has to be a reason for it being there (see Figure 5).

F

IGURE

5.

Well Shaft

Maragioglio, Rinaldi, Edward, and Petrie's observations can be reconciled by proposing that the constructed portion of the Well Shaft was originally smaller than it is now and was enlarged to allow passage into the Grand Gallery for inspecting the damage in the King's Chamber. If this is true, then perhaps the Well Shaft was designed not for human access, but for something else. Whatever this purpose was, perhaps it called for the inclusion of a large granite block within the passage to serve a specific function. These are questions I will answer later in this book.

If the Well Shaft had been dug by grave robbers, they would have needed to know the internal arrangement of the pyramid, and be sufficiently inspired by what was contained within it to undertake the project. As for the inspection theory, we might ask, "How were the guardians able to discern any subsidence on the outside of the pyramid?" With an error of only 7/8-inch over the entire thirteen-acre base, over a distance of one foot the amount of error would be only .001 inchâless than half the thickness of a human hair! To detect the 7/8-inch error in the base of the Great Pyramid, even if the base were perfectly flat originally, the ancient guardians would had to have been in possession of some remarkably advanced measuring equipment.

Assuming that they had the equipment to measure this minute variation in the pyramid's levelness, would such an insignificant deviation from accuracy warrant the penetration of the pyramid in the manner theorized? If the guardians were concerned about the fate of the internal passages and chambers, they could have put their minds at rest by closely checking the Descending Passage. As I mentioned earlier, this passage was scrutinized by Petrie who reported, "The average error of straightness in the built part of the passage is only 1/50 inch, an amazingly minute amount in a length of 150 feet. Including the whole passage the error is under 1/4 inch in the sides and 3/10 on the roof in the whole length of 350 feet, partly built, partly cut into the

rock."

8

Nonetheless, evidence indicates that an inspection of the inside chambers

of the Great Pyramid was conducted in antiquity and repairs were made. For example, plaster was daubed on the cracks of the ceiling beams above the King's Chamber. But what triggered the guardians' concern for this chamber? If they were to initiate a close inspection of the internal passages and chambers of the Great Pyramid following an earthquake, wouldn't the Descending Passage satisfy their curiosity and put their minds at ease? It would seem that the penetration of the internal chambers of the pyramid was prompted not by the detection of minute subsidence on the outside, but by other observations of the pyramid's form and function.

At the time of Al Mamun's exploration of the Great Pyramid, many untold mysteries remained hidden from his searching eyes. It was not until 1765 that Nathaniel Davison made a discovery that initiated continuing explorations and further compounded the mystery of this enigmatic structure.

Close to the King's Chamber, on the Great Step, a curious echo coming from the ceiling of the Grand Gallery caught Davison's attention. Assisted by the illumination of an elevated candle, Davison scrutinized the gallery ceiling and vaguely discerned an opening near the top. Taking his life into his hands, he erected a precarious collection of ladders and gingerly proceeded to climb to the top.

To his delight, Davison discovered that there was indeed an opening. His pleasure, though, soon turned to disgust as he wedged himself inside the hole and found himself immersed in pungent mounds of bat dung. Using a handkerchief to protect his offended nose, he forced himself into the fetid passage and struggled along in this manner for twenty-five feet until he came across a large chamber not quite high enough to stand in. Once inside this chamber, Davison cleared away bat dung and uncovered nine enormous granite beams measuring up to twenty-seven feet long and weighing up to seventy tons each. This monolithic ensemble formed the ceiling of the King's Chamber. Unlike the bottom and sides of the beams, though, the tops of them were rough-hewn with no pretension to straightness or accuracy. Davison also noticed that the ceiling of the chamber he had discovered was constructed with a similar row of granite beams. Davison could make little sense of these features, and his only satisfaction in his discovery was to carve his name on the wall and have the chamber named after himself.

Additional exploration of Davison's Chamber came in 1836 when Colonel Howard-Vyse, with the help of civil engineer John Perring, made extensive explorations of the pyramid complex at Giza. In Davison's Chamber, Howard-Vyse noticed a crack between the beams of the ceiling. He perceived the existence of yet another chamber above the one he was occupying. Without obstruction, he was able to push a three-foot-long reed into the crack. Howard-Vyse and his helpers then made an attempt to cut through the granite to find out if there was indeed another chamber above. Finding out in short order that their hammers and hardened steel chisels were no match for the red granite, they resorted to using gunpowder. A local worker, his senses dulled by a supply of alcohol and hashish, set the charges and blasted away the rock until another chamber was revealed.

This chamber held a mystery for the early explorers who entered its confines, a mystery that has baffled people for decades. The chamber was coated with a layer of black dust, which, upon analysis, turned out to be exuviae, or the cast-off shells and skins of insects. There were no living insects found in the Great Pyramid, which made this discovery even more mysterious. What prompted hordes of insects to single out this one sealed chamber and shed their skins? It is a mystery that has never been satisfactorily explained. In fact, there has not been any attempt to explain it, and because there is no logical answer that fits in with any previously proposed theory, no one has given it much attention.

As in Davison's Chamber, a ceiling of monolithic granite beams spanned this new chamber, indicating to Howard-Vyse the possible existence of yet another chamber above. Blasting their way upward for three and a half months, to a height of forty feet, they discovered three more chambers, making a total of five. The topmost chamber had a gabled ceiling made of giant limestone blocks. Howard-Vyse surmised that the reason for the five superimposed chambers was to relieve the flat ceiling of the King's Chamber of the weight of thousands of tons of masonry above. Although most researchers who have followed have generally accepted this speculation, there are construction considerations that cast doubt on this theory and prove it to be incorrect.

What Howard-Vyse and others have not considered is that there is a more efficient and less complicated technique in chamber construction elsewhere

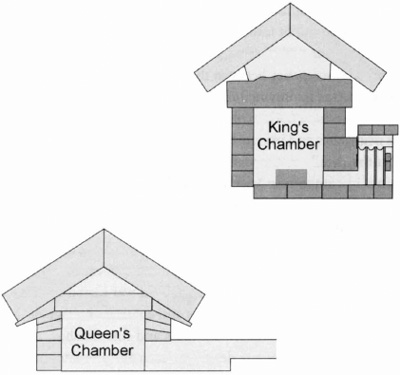

inside the Great Pyramid. The structural design of the Queen's Chamber negates the argument that the chambers overlaying the King's Chamber were designed to allow a flat ceiling. The load of masonry bearing down on the Queen's Chamber, which itself is situated below the King's Chamber, is greater than that above the King's Chamber. Yet the Queen's Chamber has a gabled ceiling, not a flat one. If a flat ceiling had been required for the Queen's Chamber, it would have been quite safe to span this room with one layer of beams similar to those above the King's Chamber. Both the King's Chamber and Queen's Chamber employ huge gabled blocks of limestone that transfer the pressure of the above masonry to the outside of the walls. The fact is that a ceiling similar to the one in the King's Chamber could have been used in the Queen's Chamber, and, as with the beams above the King's Chamber, the beams would be holding up nothing more than their own weight (see Figure 6).

When the builders of the Great Pyramid constructed the King's Chamber,

they were obviously aware of a simpler method of creating a flat ceiling. The design of the King's Chamber complex, therefore, must have been prompted by other considerations. What were these considerations? Why are there five superimposed layers of monolithic seventy-ton granite beams? Imagine the sheer will and energy that went into bringing just one of the forty-three granite blocks a distance of five hundred miles and raising it 175 feet in the air! There must have been a far greater purpose for investing so much time and energyâand there is, if we understand the Great Pyramid as a machine. But before I make my case, we must examine more of the evidence and the orthodox theories proposed to explain it.

F

IGURE

6.

Queen's Chamber and King's Chamber with Flat Ceiling

With the discovery of the five superimposed "chambers of construction" above the King's Chamber, the granite complex located at the heart of the Great Pyramid became a mystery and source of consternation. The reason the builders changed from limestone to extremely hard granite could be adequately explained if we consider egos, whims, and religious beliefs to be a driving force in the decision-making process of the ancient builders. However, there are other notable peculiarities concerning the state of some of this granite that do not fit into a logical pattern.

If we focus our attention on the granite-lined Antechamber, we perceive a marked discrepancy between the craftsmanship displayed there and the meticulous care maintained throughout the rest of the Great Pyramid. Other researchers have noticed this anomaly as well. Petrie was astounded at the gross negligence and inferior workmanship he saw in this chamber, and wrote, "In the details of the walls, the rough and coarse workmanship is astonishing, in comparison with the exquisite masonry of the casing and entrance of the pyramid; and the variation in the measures taken shows how badly pyramid masons would

work."

9

Perhaps researchers are being somewhat hard on the masons who worked on the granite complex. After all, granite is an extremely hard material with which to work, and once the pyramid was closed up, who would see it? As Petrie noted, the casing stones and entrance passage of the pyramid were tooled to a remarkable closeness and fine finish. But then, that work is in a location where any deviation from the precision of which the workers were capable would be seen by all who passed by, reflecting badly on them. It is understandable that a worker, or group of workers, would

produce the best work where it would be noticed and, perhaps, be less critical of it where it is hidden. But, as I said earlier,

everything

in the Great Pyramid has an explanation, and I believe my theory will adequately account for this variation in workmanship.