The Girls from Ames (10 page)

Read The Girls from Ames Online

Authors: Jeffrey Zaslow

Over the years, Mrs. Derby tried to locate the woman. Her full name was on Karla’s birth certificate. Mrs. Derby would go to the Ames Public Library to look through old phone books and city records, trying to figure out what became of her.

Then one day about a decade ago, Mrs. Derby came across an article in a newsletter she received through work. The author had the same first and last name as the birth mother. There was a photo of the author, a full body shot of her walking. She looked so much like Karla—tall, thin, striking—and the way she was walking, her gait, was also so completely Karla. The moment Karla saw the photo, she was certain. “I know that’s her,” she told her mother.

The woman’s article was about how cancer was prevalent in her family. She had lost her mother and a sister to breast cancer, and another sister had also been diagnosed with the disease. The article detailed the author’s anguished decision to have both breasts removed as a precaution, even though she had no sign of cancer.

Understandably, Karla was upset by the article. If this woman was her birth mother, what cancer risks had Karla passed on to her three children? She went to the doctor to be tested and was told she showed no signs of cancer. Still, the uncertainties raised by the article remained with her.

Mrs. Derby felt 99 percent sure that she had found the right woman, and one night she worked up the courage to call her. The woman answered some questions, declined to answer others, and was vague about several points. She insisted she was not Karla’s mother, and Mrs. Derby ended the call without confirmation that her suspicions were true. Karla, however, needed no convincing.

“We found her. That’s her,” Karla said. “But she never wanted me and she now wants nothing to do with me. All I’d want from her is a medical history. I feel that’s what she owes me. And if she’s not going to give me that, then we’ll have to live with it. You’re my mother. I don’t need her.”

K

arla’s relationship with the other ten Ames girls began forming in infancy. She and Jenny were babies together in the same church nursery during Sunday services. They’d take naps in adjoining bassinets.

arla’s relationship with the other ten Ames girls began forming in infancy. She and Jenny were babies together in the same church nursery during Sunday services. They’d take naps in adjoining bassinets.

Karla met Diana at Fellows Elementary School. Diana was the prettiest girl in the popular group, and Karla would see her playing with her other pretty friends at recess. “Those of us in the unpopular group, we were in awe of them,” Karla says. It wasn’t just that the girls were pretty. It was how they carried themselves through recess, with this air of confidence, no matter if they were on the swings or playing kickball or just standing around talking.

Karla tiptoed her way into Diana’s popular group in seventh grade at Central Junior High. There was a boy-girl party and, somehow, she and Jenny were invited. Karla couldn’t believe her good fortune. She thought to herself, “Wow, we’ve finally made it!” The party turned out to be a mind-opener for them. Right there on the couches, boys and girls were making out in plain view. Hands were everywhere. Kisses were long and wet. It was so much more than Karla expected. She was too overwhelmed to participate.

Karla remained painfully shy and insecure around boys for most of her childhood. That partly was because she was flat-chested longer than the other girls were. She was taller, too, and that felt like a handicap. In the presence of boys, she didn’t know what to say, didn’t feel smart, couldn’t always articulate herself, didn’t realize she was as beautiful as she was. Kelly thought that Karla never tried too hard to make herself appealing to boys. When other girls were discovering their sexuality, Karla seemed to be holding it at bay.

She ended up going to her share of junior-high and high-school dances, but they were always affairs in which the girls got to ask the boys. She’d get up her courage, ask a boy to be her date, and by the end of the night, she’d have another formal, five-by-seven portrait—of her and a boy, all dressed up, uncomfortably holding hands—to place in her scrapbook.

When she was with the ten other Ames girls, Karla was far more self-assured. She had a sense of humor that was self-deprecating, with few inhibitions. For the girls’ amusement, on demand, she could stick her entire fist in her mouth. No one in Ames—certainly no girl—had that combination of a small hand and a large mouth, and if they did, no one was as willing as Karla to prove that one fit into the other.

Karla was sometimes the goofiest, most fun-loving of the Ames girls. Before they had their driver’s licenses, several of them tooled around town on those mini-motorcycles called mopeds. One Halloween, Karla swiped a large carved pumpkin from Karen’s house. She put her head through the hole in the pumpkin, looked out through the carved-out eyes, and was able to mount her moped and drive it over to Cathy’s house, with Karen riding in back. As she pulled up, she looked like some crazy half-human/half-pumpkin escapee from Planet Jack-o’-Lantern. Cathy’s mother saw them coming and couldn’t stop laughing.

Karla was also a bit of a pop-culture princess, always eager to apply things she read about in her teen magazines, or saw on TV, to the lifestyles of Ames inhabitants.

When the movie

10

came out in 1979, Karla convinced the others that Karen, who had the longest hair, needed to get the full Bo Derek cornrow treatment. It took the girls hours to get the job done. “She looked so great,” Karla recalls. “She was shaking it all around. She thought she was really hot.” Soon enough, that didn’t sit well with the others.

10

came out in 1979, Karla convinced the others that Karen, who had the longest hair, needed to get the full Bo Derek cornrow treatment. It took the girls hours to get the job done. “She looked so great,” Karla recalls. “She was shaking it all around. She thought she was really hot.” Soon enough, that didn’t sit well with the others.

Someone had to say it: “Who the hell does she think she is? Bo Derek?”

Karen was taken aback. She was swinging her hair around mainly to give her cornrow-installation team a thrill. “When I finally saw myself in the mirror,” she says, “the cornrows were so crooked. Some were big. Some were small. My hair didn’t look like Bo Derek’s at all.” She didn’t have the heart to tell the girls that, even after they decided she’d gotten too full of herself. Eventually, Karla figured out the dynamics and owned up to it. “I guess the rest of us just got jealous. Sorry.”

Back in the seventies, aluminum-colored reflective tanning blankets were advertised on TV, and Karla, who always had the best tan in the group, decided that she and the other girls needed to buy some.

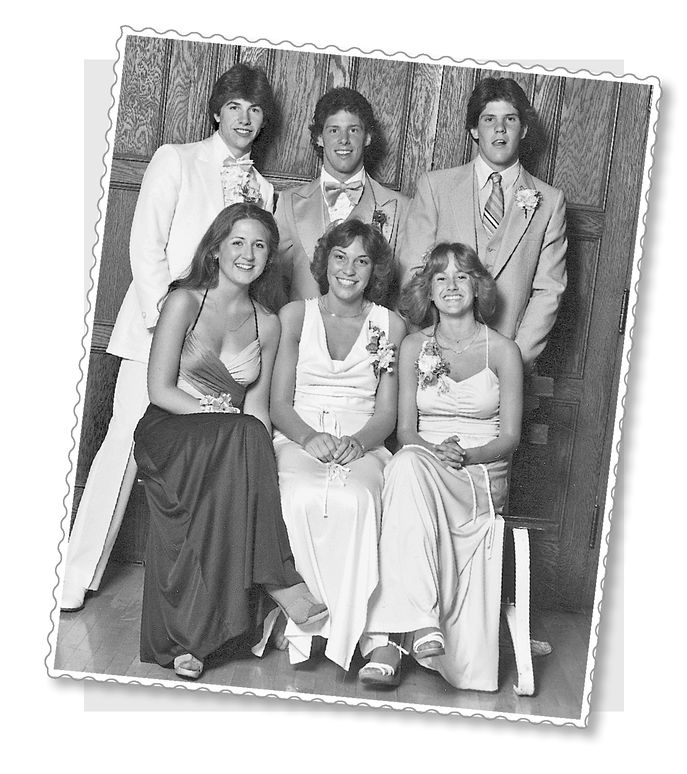

Karen, Karla, Diana and their prom dates

One spring day, Sheila, Sally and Jenny skipped school with her and they all sat in her backyard, tanning on those weird sparkly silver blankets. They looked like they were lying on flattened astronaut suits. It was a short-lived adventure, however, because Karla’s father caught them and—they couldn’t believe he’d be such a party pooper—turned them in to the school principal. Their aluminum tans faded, but the detention slip was proudly displayed for posterity in Karla’s ever-growing scrapbook.

For Karla, scrapbooking was risky business. On the one hand, she wanted to document everything going on in her life. On the other hand, if her parents came upon the scrapbooks, they’d have evidence of things she didn’t want them to know about. In the end, her urge to preserve her memories almost always won out, and so she became a scrapbook risk-taker, pasting in everything from notes passed between her and the other Ames girls (about real and humorously imagined liaisons with boys) to photos of everyone holding a beer at a party.

In one scrapbook, she had photos of the girls sitting in a sea of stoned Iowans at a Ted Nugent concert. In another, she posted photos of her dad’s car covered with huge clumps of mud and cornstalks. There was a story behind that one, of course. She had just gotten her license and, with Sheila riding shotgun, had accidentally driven the car into a ditch. A farmer happened by on his tractor and pulled out the car, but by the time he got it back onto the roadway, it looked like it had been swallowed up by a cornfield. Karla and Sheila hosed it off with a few hundred gallons of water from the garden hose. “My parents can never find out,” Karla told Sheila. “Never. This car has to be spotless!”

Still, she couldn’t resist taking before-and-after photos so she could show all the other girls proof of the adventure. And after she carefully preserved the memory in her scrapbook, she casually left it lying around her room.

Her parents never went through that scrapbook, though they weren’t completely in the dark about things. Karla’s mom recalls a night when several of the Ames girls’ mothers decided to meet at a bar. They shared stories and compared notes, had a few drinks and some laughs. “We knew the girls were doing some things we wouldn’t want them to do,” says Mrs. Derby. “But we knew they were good girls inside, and they were good for each other. They’d be OK.”

F

rom the time Karla and the other Ames girls were in their early teens, they always tried to get jobs together. Each job carried its own secrets or naughty moments or lessons learned. Several summers when they were in junior high, the girls worked together detasseling corn. What sounded like a wholesome summer job was actually hot, dirty, itchy labor—the hardest work they had ever done in their lives. It was also an eye-opener for them. The older boys on the crew would gather among the farthest cornstalks to smoke pot. And their crew leader was a woman with enormous breasts who, after dark, was a champion wet T-shirt contest winner.

rom the time Karla and the other Ames girls were in their early teens, they always tried to get jobs together. Each job carried its own secrets or naughty moments or lessons learned. Several summers when they were in junior high, the girls worked together detasseling corn. What sounded like a wholesome summer job was actually hot, dirty, itchy labor—the hardest work they had ever done in their lives. It was also an eye-opener for them. The older boys on the crew would gather among the farthest cornstalks to smoke pot. And their crew leader was a woman with enormous breasts who, after dark, was a champion wet T-shirt contest winner.

Later, when they were fifteen, the girls found jobs that were easier and more fun. Karla and six of the others signed on at Boyd’s, the ice-cream shop famous for its big plastic cow out front. The girls often had the run of the place. Mr. and Mrs. Boyd, the owners, weren’t always there, nor was the manager. So the girls often felt a rush of power—as if they controlled all the ice cream in Ames.

In the late 1970s, Channel 5 in Ames had a promotional campaign for the station, showing upbeat scenes around town. There was a catchy jingle with the station’s motto: “5’s the one!” For one spot, the film crew stopped by Boyd’s and got shots of the girls dipping five giant scoops of ice cream onto one cone.

That was the only time they were filmed at the store. Lucky thing, too. They wouldn’t have fared too well if the Boyds had ever installed hidden cameras to monitor them.

When things were slow, the girls would sit on the counter licking ice-cream cones, chatting away. And when things got busy, they could be very magnanimous. They were the guardians of the ice-cream containers, and the cuter the customer, the less likely he was to have to reach into his pocket. Two good-looking boys would walk in. Free ice cream for them. Friends and family would stop by. Cones and malts were on the house. If an entire boys baseball team came through the door, Karla and the other girls would fight off the urge to give them whatever they wanted free of charge. Once, Karen gave her siblings free ice cream, and when her dad found out, he was horrified and told her she had to return her next paycheck to Mr. and Mrs. Boyd, as repayment for all of the pilfered profits.

It hadn’t exactly occurred to the girls that their generosity at the ice-cream counter wasn’t fair to the Boyds. When you’re young and there’s ice cream available, you just feel this urge to spread it around.

Usually, enough ice cream was sold to keep the Boyds in the black, but there were times when the girls unintentionally damaged the shop’s bottom line. One night after work, Karla and Sally were asked to defrost all of the ice-cream freezers. It took a while, and then they headed to Karla’s house for a sleepover. In the morning, Sally asked Karla, “Did you plug the freezers back in?”

Karla replied, “No, I thought you did.”

Panicked, they called Mrs. Boyd, who met them at the shop. Sure enough, everything had melted into goop: ten gallons each of twenty-five flavors.

The girls stood there, looking at the goop, staring at their feet. Finally, Mrs. Boyd said, “Well, girls, that was an expensive mistake, wasn’t it?”

She didn’t make them pay for the lost inventory, and they didn’t lose their jobs. But Karla and Sally shared the bond of feeling guilty and stupid and of disappointing Mrs. Boyd.

Before leaving high school in 1981, Sally filled out a Boyd’s gift certificate, addressed it to herself, and pasted it into her scrapbook: “To Sally Brown: 20 extra thick malts.” In the space labeled “valid for” she wrote: “50 years from date of issue.”

The certificate would have been good until 2031—when she and Karla and the others could return as senior citizens for two malts apiece—but it’s now unredeemable. Boyd’s, which opened its doors in 1941, closed in 1987. Mrs. Boyd died in 2004.

M

idway through high school, skinny, flat-chested Karla began to fill out, and the other girls knew that her moment would soon come. They kept telling her that, and they were right. By senior year, she was dating Kurt, an Ames High football player. He might not have been the first boy to notice Karla, but he was the first to show great interest in her, and she fell for him.

idway through high school, skinny, flat-chested Karla began to fill out, and the other girls knew that her moment would soon come. They kept telling her that, and they were right. By senior year, she was dating Kurt, an Ames High football player. He might not have been the first boy to notice Karla, but he was the first to show great interest in her, and she fell for him.

Kurt was very attractive and popular with the jock crowd—the sort of fun, macho guy who seemed like a necessary ingredient at a Friday night keg party. He wasn’t tall, but he had wavy brown hair, a jock’s body and a chiseled face with a nice smile, despite two chipped teeth. He was always a sharp dresser, and he’d drive around town in a white 1975 Monte Carlo, a car celebrated for its long hood and state-of-the-art concealed windshield wipers.

Other books

Just Cause Universe 3: Day of the Destroyer by Ian Thomas Healy

Legally Bound by Saffire, Blue

Laurie's Wolves by Becca Jameson

Our Last Time: A Novel by Poplin, Cristy Marie

What You Do To Me (Unexpected Love) by Cullen, Izzy

Nightwatcher by Wendy Corsi Staub

Ablutions by Patrick Dewitt

Corrigan Rage by Helen Harper

Bride of the Baja by Toombs, Jane

Here She Rules: The Chronicles of Erla: Book 1 by Kat Brewer