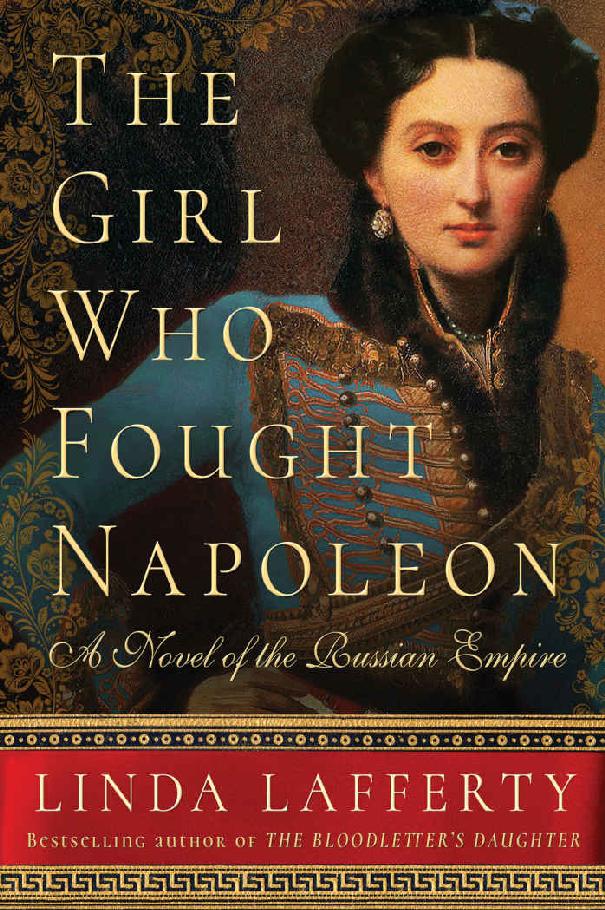

The Girl Who Fought Napoleon: A Novel of the Russian Empire

Read The Girl Who Fought Napoleon: A Novel of the Russian Empire Online

Authors: Linda Lafferty

ALSO BY LINDA LAFFERTY

The Bloodletter’s Daughter

The Drowning Guard

House of Bathory

The Shepherdess of Siena

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Text copyright © 2016 Linda Lafferty

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Lake Union Publishing, Seattle

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Lake Union Publishing are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

ISBN-13: 9781503937260

ISBN-10: 1503937267

Cover design by

Shasti O’Leary-Soudant

To my beloved mother, Elizabeth Vissering Lafferty, who was fascinated by St. Petersburg, Napoleon, and European history.

And to my father, Frederick Reid Lafferty, Jr., who loved my mother with all his heart.

Contents

Prologue

Yelabuga, Russia

February 1864

He will have questions. I must have answers.

A wind is howling, hurling crystals of ice against the window. The pleasant tinkling sound has grown fierce, the driving snow threatening to shatter the glass. But I do not close the shutters. I want to see him the moment he arrives. How he walks. If he touches his hat with his fingertips, muffles his face against the cold.

I have waited years for this reunion. I do not want to miss a second of his presence here in Yelabuga. Such a remote place in Russia for such an honored visitor.

How long has it been since I have had a guest in this house? Not since my father’s death.

Living alone suits me. No visitors.

Except for this one. Yes, I will admit him—and only him.

How can he travel from Moscow in such a wolf of a storm? I look out the window at the pelting snow, listening for the bells of his sleigh.

Babushka, one of many stray cats who have settled in with me, meows plaintively, begging for a caress. “Not now, my princess,” I tell her. “I must prepare for his visit. Indulge me, won’t you?”

I hear the scratching at the door to the hall—an old dog, Sasha, too old now to survive in the outdoor kennel with the rest of the hounds. My maid scolds him, pulling him away from the door.

I drag my fingertips over the once finely polished wood of my mother’s china cabinet. A layer of silky cat hair coats everything. Wrinkled strands of tobacco mingle with the animal fur and motes of dust rise as I wipe my sleeve over the furniture.

It is hopeless. I have never been known for housekeeping!

But never mind that! This guest deserves above all others my story. I must remember faithfully, no matter how hard it is to recall such distant memories.

Nadezhda,

make yourself remember!

Yes, I remember. I can tell the story. But I think there are two stories to tell.

Feodor Kuzmich is dying.

He lies on a sweat-soaked straw mattress, a coarse blanket clutched in his skeletal fingers. A bowl of milk stands curdled by his bedside, the only nourishment he had taken in the last two weeks. The old starets, a holy mystic, is determined to die here in his cabin in the northern wilds of Siberia.

The life he has lived is written clearly in the lines and creases of his face. He is nearly deaf, but his eyesight is still keen. A tall candle burns near the window, melting a clear circle through the ice on the glass, and Feodor Kuzmich gazes out at the hollow belly of winter enveloping his cabin. The icy fingers of bare birch trees scratch at his window as the wind blows across the Siberian plains.

He can see the pine trees bowed low under their heavy load of snow, more featureless mounds of white than living trees as the Siberian storm envelops the frozen plains and the tiny cabin.

His glassy eyes are fixed on the window, but his mind roams far and free, remembering St. Petersburg and the emperor who once reigned, so many years ago.

He smiles in delirium as he stares out into the storm. He remembers a soldier, slim and youthful . . . with such a delicate face.

Where is that soldier now?

Part 1

Two Young Lives

Chapter 1

Pirjatin, the Ukraine

1783

I was named Nadezhda after my mother, who was born Nadezhda Aleksandrovicheva in the Ukrainian village of Pirjatin, a three-day ride east from Kiev. She was a willful girl of rare beauty: raven haired, bone-white skin and blue eyes, her voice low and seductive, except when she lost her temper.

She was pursued by men from Pirjatin to Kiev, but none was heroic enough for my headstrong mother—until she met Andrej Vasilevich Durov, a dashing dark-haired captain with the Russian Hussars. She fell madly—and recklessly—in love.

My wealthy grandfather, a proud Ukrainian, threatened to disown her when she began keeping company with Captain Durov. Though my father was a man of gentle disposition and impeccable manners, he was a Russian. No failing could be more vile in the eyes of my grandfather.

“My daughter marry a Muscovite! They who disdainfully call our Ukraine ‘Little Russia’! As if they were petting a dog’s head. An insult! How could you offend me with such behavior?”

“But he is of Polish family! His Russian blood is diluted!” argued my besotted mother. “And I mean to marry him, Papa!”

Of course my grandfather forbade the marriage and any further visits from Andrej Vasilevich Durov. My grandfather prided himself on his obstinacy, regarding it as a mark of character. There would be no compromise.

But he should have known his daughter had inherited the same stubbornness, her head as impenetrable as Ukrainian oak. One night in the teeth of a howling storm, Nadezhda Aleksandrovicheva crept across the bedroom, careful not to awaken her sleeping sister in the bed next to her. Cloak and hood in hand, she tiptoed into the drawing room and out into the garden. She unlatched the gate and flung herself into Captain Durov’s arms.

And so she left her father’s home and the Ukraine forever.

A carriage drawn by four horses led them away into the stormy autumn night. As the rain splattered against the coach, they embraced under the warmth of bearskin furs, swearing their love. They were married in the first village they came to and then traveled on to Kiev to join my father’s Hussar squadron.

Nadezhda Aleksandrovicheva soon discovered the true life of a cavalry wife. In peacetime, the families traveled along with the officers, bumping along rutted roads throughout the vast Russian Empire. Quarters were requisitioned from village to village, each night a different home. My mother, who had never known discomfort or travel, was given a handmaid to attend her, but the life of a Hussar captain’s wife was never easy.

For two years my mother wrote to her father, begging forgiveness. She received no reply.

If only I could have a son to recapture my father’s heart! A boy as dashing on a horse as my own Andrej Durov. He will be half Ukrainian—how could Father not love him?

And imagining this baby boy as her savior, she fell in love with her own dream. The boy that she would bear would be as handsome as Cupid, adoring and devoted to his mother.

Two years later she fought through a difficult birth in a Siberian log house near the cavalry encampment, attended only by a wizened old

midwife

.

The woman insisted on letting blood to ease the spasms of childbirth that left my mother in agony.

Amid her hysterical screams, I was born.

“Let me see my darling boy!” my mother cried, still delirious from the loss of blood. “Give me my child, my son!”

But instead of the son she had dreamed of, she was given me, her most grievous disappointment. A baby girl with thick wavy hair, bawling at the top of my lungs. My mother pushed me from her lap and turned her face to the wall.

This was the start of our life together. Perhaps I sensed her animosity, for I refused to suckle at her breast. Instead I bit her nipple, causing her to screech in pain.

From then on, I was fed on the milk of peasant women as the cavalry marched through village after village. Every day a scout would ride ahead to find a nursing mother who could give me her teat for the night.

My mother suffered from lack of sleep, for I was a fitful baby. Perhaps the constant change of milk—cow’s milk during the day, a stranger’s breast at night—was the source of my colic. Despite the dust and jolting of the horse-drawn carriage I would sleep during the day, but come sunset I pierced the night with my screams.

One day when I was only a few months old, my mother suffered a fit of rage. At daybreak the cavalry had broken camp and set off on orders toward Kherson, a port in Crimea on the Black Sea. Because of my crying, my mother had not slept in many nights. She took me from the cradle into her arms, hoping for peace at last in the coach, but that day I awoke and began to bawl.

“Stop howling, you miserable brat!” she screamed, thrusting me into her maid’s arms. “How your birth has cursed me!”

I bawled in red-faced rage, hour upon hour into the heat of the summer day, with the dust filtering through the curtains. Flies skipped over our skin, clinging to my tear-stained face. Clapping her hands over her ears, my mother could not escape my screams of fury. Finally, at the hottest hour of the day, my mother could endure my cries no longer.

She snatched me from the maid’s arms and threw me out the carriage window!

The Hussars gasped in horror.

My father’s orderly, Astakhov, spun his horse around, seeing me lying as still as a wooden doll in the road. Shouting up the ranks to my father, Astakhov vaulted off his horse to rescue me before my skull was crushed by horses’ hooves or the rolling wheels of the wagons. He snatched me up from the dusty track, cradling me against the thick braid of his uniform. Tears spilled from his eyes, leaving streaks of mud down his dusty face. He examined my bloody face and bleeding nose as I stared back at him dazed and silent.

“You!” called my mother from the coach. “Give her to me!”

Astakhov began walking toward my mother’s carriage to surrender me, though his boots dragged reluctantly. He clutched me tighter to his breast.

A cloud of dust enveloped us.

“Wait! Give me the baby!” My father’s voice cut through the drama. Astakhov passed me up to his captain, blood still streaming from my mouth and nose, staining his uniform.

Astakhov told me later that my father cradled me in one arm, his other hand on the reins. He raised his eyes to the heavens to thank God that I was still alive, then rode to the carriage and screamed at my mother, “Give thanks to God that you are not a murderess! I will care for her myself.”

And so began my life in the cavalry.