The Ghost in the Machine (10 page)

be the Department of Immigration. In order to operate as a self-reliant

unit, the department must be equipped with a set of instructions and

regulations enabling it to take routine contingencies in its stride,

without having to consult higher authority in each particular case. In

other words, what enables the department to function in this efficient

way, as an autonomous holon, is once more a set of fixed rules,

its

canon

. But here again there will be cases where the rules can

be interpreted in this way or that, and so leave room for more than

one decision. Whatever the nature of a hierarchic organisation, its

constituent holons are defined by

fixed rules

and

flexible

strategies

.

guide the conduct of the people who work in the department are not the

same as the rules which determine the actions of the department. Mr Smith

may be willing to grant a visa to an applicant on grounds of compassion,

but the regulations say differently. And we find a further parallel to

previous examples (

p. 43

).

When the rules allow more than one course of action, the matter must be

referred to the head of the department, who might find it advisable

to appeal for a decision to a higher level of the hierarchy. And

there again, strategic considerations of a higher order may arise --

such as the availability of housing, the colour problem, the labour

situation. There may even be conflict between Home Offce policy and the

Ministry of Economics. Once more we are moving in a regressing series

(although in this case, of course, it is not an infinite regress).

of the body social that each of its sub-divisions should operate as an

autonomous, self-reliant unit which, though subject to control from above,

must have a degree of independence and take routine contingencies in its

stride, without asking higher authority for instructions. Otherwise the

communication channels would become overloaded, the whole system clogged

up, the higher echelons would be kept occupied with petty detail and

unable to concentrate on more important factors.

as negative

constraints

imposed on its actions, but also as positive

precepts

, maxims of conduct or moral imperatives. As a consequence,

every holon will tend to persist in and assert its particular pattern of

activity. This

self-assertive tendency

is a fundamental and universal

characteristic of holons, which manifests itself on every level of the

social hierarchy (and, as we shall see, in every other type of hierarchy).

-- ambition, initiative, competition -- is indispensable in a dynamic

society. At the same time, of course, he is dependent on, and must be

integrated into, his tribe or social group. If he is a well-adjusted

person, the self-assertive tendency and its opposite, the

integrative

tendency

, are more or less equally balanced; he lives, so long as

things are normal, in a kind of dynamic equilibrium with his social

environment. Under conditions of stress, however, the equilibrium is

upset, leading to emotionally disordered behaviour.

inward, sees himself as a self-contained unique whole, looking

outward as a dependent part. His

self-assertive

tendency is the

dynamic manifestation of his unique

and independence as a holon. Its equally universal antagonist,

the

integrative tendency

, expresses his dependence on the

larger whole to which he belongs: his 'part-ness'. The polarity of

these two tendencies, or potentials, is one of the leitmotivs of the

present theory. Empirically, it can be traced in all phenomena of life;

theoretically, it is derived from the part-whole dichotomy inherent in the

concept of the multi-layered hierarchy; its philosophical implications

will be discussed in later chapters. For the time being let me repeat

that

the self-assertive tendency is the dynamic expression of the

holon's wholeness, the integrative tendency, the dynamic expression of

its partness

.*

* In The Act of Creation I talked of self-assertive andThe manifestations of the two tendencies on different levels go by

'participatory' tendencies; but 'integrative' appears to be the

more appropriate term.

different names, but they are expressions of the same polarity running

through the whole series. The self-assertive tendencies of the individual

are known as 'rugged individualism', competitiveness, etc.; when we

come to larger holons we speak of 'clannishhess', 'cliquishness',

'class-consciousness', 'esprit de corps', 'local patriotism',

'nationalism', etc. The integrative tendencies, on the other hand, are

manifested in 'co-operativeness', 'disciplined behaviour', 'loyalty',

'self-effacement', 'devotion to duty', 'internationalism', and so on.

Note, however, that most of the terms referring to higher levels of the

hierarchy are ambiguous. The loyalty of individuals towards their clan

reflects their integrative tendencies; but it enables the clan as a whole

to behave in an aggressive, self-assertive way. The obedience and devotion

to duty of the members of the Nazi S.S. Guard kept the gas chambers

going. 'Patriotism' is the virtue of subordinating private interests to

the higher interests of the nation; 'nationalism' is a synonym for the

militant expression of those higher interests. The infernal dialectic of

this process is reflected throughout human history. It is not accidental;

the disposition towards such disturbances is inherent in the part-whole

polarisation of social hierarchies. It may be the unconscious reason why

the Romans gave the god Janus such a prominent role in their Pantheon

as the keeper of doorways, facing both inward and outward, and why they

named the first month of the year after him. But it would be premature

to go into this subject now; it will be one of our main preoccupations

in

Part Three

of this volume.

For the time being we are only concerned with the normal, orderly

functioning of the hierarchy, where each holon operates in accordance

with its code of rules, without attempting to impose it on others,

nor to lose its individuality by excessive subordination. It is only

in times of stress that a holon may tend to get out of control, and

its normal self-assertiveness changes into aggressiveness -- whether

the holon is an individual, or a social class, or a whole nation. The

reverse process occurs when the dependence of a holon on its superior

controls is so strong that it loses its identity.

Readers versed in contemporary psychology will have gathered, even

from this incomplete preliminary outline, that in the theory proposed

here there is no place for such a thing as a destructive instinct; nor

does it admit the reification of the sexual instinct as the

only

integrative force in human or animal society. Freud's Eros and Thanatos

are relative late-comers on the stage of evolution: a host of creatures

that multiply by fission (or budding) are ignorant of both.* In our

view, Eros is an offspring of the integrative, destructive Thanatos of

the self-assertive tendency, and Janus the ultimate ancestor of both --

the symbol of the dichotomy between partness and wholeness, which is

imeparable from the open-ended hierarchies of life.

* For a discussion of Freudian metapsychology,Summary

see Insight and Outlook, Chapters XV, XVI.

Organisms and societies are multi-levelled hierarchies of semiautonomous

sub-wholes branching into sub-wholes of a lower order, and so on. The

term 'holon' has been introduced to refer to these intermediary entities

which, relative to their subordinates in the hierarchy, function as

self-contained wholes; relative to their superordinates as dependent

parts. This dichotomy of 'wholeness' and 'partness', of autonomy and

dependence, is inherent in the concept of hierarchic order, and is called

here the 'Janus principle'. Its dynamic expression is the polarity of

the Self-Assertive and Integrative Tendencies.

Hierarchies are 'dissectible' into their constituent branches, on which

the holons form the 'nodes'. The number of levels which a hierarchy

comprises is called its 'depth', and the number of holons on any given

level its 'span'.

Holons are governed by fixed sets of rules and display more or less

flexible strategies. The rules of conduct of a social holon are not

reducible to the rules of conduct of its members.

The reader may find it helpful to consult from time to time Appendix I,

which summarises the general characteristics of hierarchic systems as

proposed in this and subsequent chapters.

IV

INDIVIDUALS AND DIVIDUALS

I have yet to see any problem, however complicated, which when youA Note about Diagrams

looked at it the right way did not become still more complicated.

Poul Anderson

Before we turn from social organisation to biological organisms, I must

briefly remark on various types of hierarchies and their diagrammatic

representation.

There have been several attempts to classify hierarchies into categories,

none of them entirely successful, because unavoidably the categories

overlap. Thus one can broadly distinguish between 'structural'

hierarchies, which emphasise the spatial aspect (anatomy, topology)

of a system, and 'functional' hierarchies, which emphasise process in

time. Evidently, structure and function cannot be separated, and represent

complementary aspects of an indivisible spatio-temporal process; but it

is often convenient to focus attention on one or the other aspect. All

hierarchies have a 'part within part' character, but this is more easily

recognised in 'structural' than in 'functional' hierarchies -- such as the

skills of language and music which weave patterns within patterns in time.

In the type of administrative hierarchy we have just discussed, the

tree diagram symbolises both structure and function -- the branches are

lines of communication and control, the nodes or boxes each represent a

group of physically real people (the department head, his assistants and

secretaries). But if we chart in a similar way a military establishment,

the tree will only represent the functional aspect, because, strictly

speaking, the boxes on each level whether they are labelled 'battalion'

or 'company' -- will contain only officers or N.C.O.s; the place for the

other ranks which makes up the bulk of the battalion or company is in the

bottom row of the chart. For our purposes this does not really matter,

because what we are interested in is how the machinery is functioning,

and the tree shows exactly that -- it is the officers and N.C.O.s who

determine the operations of the holon as repositories of its fixed

rules and makers of strategy. But people who are inclined to think

in concrete images, rather than in abstract schemata, often find this

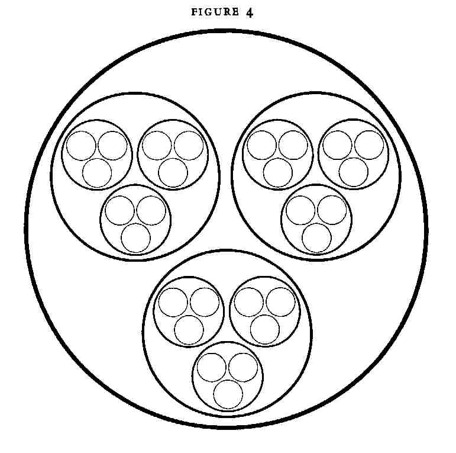

rather confusing. If, however, we wanted to emphasise the

structural

aspect of an army, we might draw a diagram, such

as Figure 4 below, which shows how platoons are 'encapsulated' into

companies, companies into battalions, etc. But such structural diagrams

are clumsy, and contain less information than the branching tree.

symbolic hierarchies

(language, music,

mathematics) into a separate category; but they might just as well be

classified as 'functional hierarchies', as they are produced by human

operations. A book consists of chapters, consisting of paragraphs,

consisting of sentences, etc.; and a symphony can similarly be dissected

into parts within parts. The hierarchic structure of the product reflects

the hierarchic nature of the skills and subskills which brought it

into being.

In a similar way, all

classificatory hierarchies

, unless they are purely

descriptive, reflect the processes by which they came into being. Thus

the species-genus-family-order-class-phylum classification of the animal

kingdom is intended to reflect relations in evolutionary descent -- here

the tree diagram represents the archetypal 'tree of life'. Similarly, the

hierarchically subdivided subject-index in library catalogues reflects

the hierarchic ordering of knowledge.

Lastly, phylogeny and ontogeny are

developmental hierarchies

in which

the tree branches out along the axis of time, the different levels

represent different stages of development, and the holons -- as we shall

see -- reflect intermediary structures at these stages.

It may be useful to repeat at this point that the search for properties

or laws which all these varied kinds of hierarchies have in common is

more than a play on superficial analogies. It could rather be called an

exercise in 'general systems theory' -- a relatively recent branch of

science, whose aim is to construct theoretical models and 'logically

homologous laws' (v. Bertalanffy) which are universally applicable to

inorganic, biological and social systems of any kind.

Inanimate Systems

As we move downward in the hierarchy which constitutes the living

organism, from organs to tissues, cells, organelles, macro- molecules,

and so on, we nowhere strike rock bottom, find nowhere those ultimate

constituents which the old mechanistic* approach to life led us to

expect.

The hierarchy is open-ended in the downward, as it is in

the upward direction.

The atom, itself, although its name is derived

from the Greek for 'indivisible' has turned out to be a very complex,

Janus-faced holon. Facing outward, it associates with other atoms as

if it were a single unitary whole; and the regularity of the atomic

weights of elements, closely approximating to integral numbers, seemed

to confirm the belief in that indivisibility. But since we have learned

to look inside it, we can observe the rule-governed interactions between

nucleus and outer electron-shells, and of a variety of particles within

the nucleus. The rules can be expressed in sets of mathematical equations

which define each particular type of atom as a holon. But here again, the

rules which govern the interactions of the sub-nuclear particles in the

hierarchy are not the same rules which govern the chemical interactions

between atoms as wholes. The subject is too technical to be pursued here;

the interested reader will find a good summary in H. Simon's paper,

which I have quoted before. [1]

* Throughout this book, the term 'mechanistic' is used in itsWhen we turn from the universe in miniature to the universe at large,

general sense, and not in the technical sense of an alternative

to 'vitalistic' theories in biology.

we again find hierarchic order. Moons go round planets, planets

round stars, stars round the centres of their galaxies, galaxies form

clusters. Wherever we find orderly, stable systems in Nature, we find

that they are hierarchically structured, for the simple reason that

without such structuring of complex systems into subassemblies, there

could be no order and stability -- except the order of a dead universe

filled with a uniformly distributed gas. And even so, each discrete gas

molecule would be a microscopic hierarchy. If this sounds by now like

a tautology, all the better.*

* Often, however, we fail to recognise hierarchic structure,It would, of course, be grossly anthropomorphic to speak of

for example in a crystal, because it has a very shallow hierarchy

consisting of only three levels (as far as our knowledge goes) --

molecules -- atoms -- sub-atomic particles; and also because the

molecular level has an enormous 'span' of near-identical holons.

'self-assertive' and 'integrative' tendencies in inanimate nature, or of

'flexible strategies'. It is nevertheless true that in all stable dynamic

systems, stability is maintained by the equilibration of opposite forces,

one of which may be centrifugal or separative or inertial, representing

the quasi-independent, holistic properties of the part, and the other

a centripetal or attractive or cohesive force which keeps the part

in its place in the larger whole, and holds it together. On different

levels of the inorganic and organic hierarchies, the polarisation of

'particularistic' and 'holistic' forces takes different forms, but it is

observable on every level. This is not the reflection of any metaphysical

dualism, but rather of Newton's Third Law of Motion ('to every action

there is an equal and opposite reaction') applied to hierarchic systems.

There is also a significant analogy in physics to the distinction between

fixed rules and flexible strategies. The geometrical structure of a crystal

is represented by fixed rules; but crystals growing in a saturated solution

will reach the same final shape by different pathways, i.e., although their

growth processes differ in detail; and even if artificially damaged in the

process, the growing crystal may correct the blemish. In this and many other

well-known phenomena we find the self-regulatory properties of biological

holons foreshadowed on an elementary level.

Other books

Misty Blue by Dyanne Davis

Fall on Your Knees by Ann-Marie Macdonald

Dead Drop (A Spider Shepherd short story) by Leather, Stephen

The Duke Dilemma by Shirley Marks

The Highlander's Touch by Karen Marie Moning

Beyond Asimios - Part 4 by Fossum, Martin

Ordinary Grace by William Kent Krueger

Kingdoms in Chaos by Michael James Ploof

Cyber War: The Next Threat to National Security and What to Do About It by Richard A. Clarke, Robert K. Knake

Drifters by Santos, J. A.