The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (30 page)

Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

1

Ben Hubbard, “Separate roads push West Bank Arabs to the byways”,

The Guardian

, June 13, 2010. Archived at

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/feedarticle/9215464

.

2

Magav is the acronym for

Mishmar HaGvul

, which means “border patrol” in Hebrew.

PART IV

Hope for Peace

The Next Generation

On a sunny winter morning, the view from my childhood bedroom in Motza is breathtaking. Every leaf of every tree and shrub seems delighted to feel the sun after a long, cold night. The view is a tapestry of shades, from yellow-green to the deep dark of evergreens. There are flowers embedded in this composition, coral and fuchsia. And the clean blue Mediterranean sky. It’s hard to look away.

I am able to return to this spot only three or four times each year and only for a few weeks at a time. When I do visit Israel/Palestine, I am busy meeting people and crossing over to the Palestinian side of the wall, and it feels like I am consumed with activity. But, when I am there at my mother’s house, the house I grew up in, I try to take in as much of the moment as possible.

It’s not easy leaving my life in Coronado—my karate school, Gila and our three children—even for just a few weeks. Gila is busy running her own business, an acupuncture clinic. Usually a lot of planning goes into my departure, so that things continue to run smoothly. Over the years my staff of instructors and administrators have learned that this is my reality: I live in one place and my heart is quite often in another.

And while it’s true that these trips are often motivated by activist missions, I also travel because I like to visit my mother and see the rest of the family as much as possible.

Although in her eighties, my mother Zika keeps a busy, healthy schedule. She sleeps well and exercises by swimming and taking yoga classes. The real secret to her health is her garden, the earth into which she pours her heart and which, in return, yields magnificent blossoms every day of the year, even on the hottest and driest days of the Jerusalem summer. She does this by conserving water and recycling every drop so that she can give it to her plants. She’s in her garden every day first thing in the morning, digging her hands deep into the fine earth around her house. The plants and birds seem grateful. In the early hours of dawn, as the sky turns from black to purple, you can hear the birds sing their morning songs, as though praising the beauty Zika has created for them—and for the rest of us—to enjoy.

It was my mother who instilled in me a love of children, and it’s largely thanks to her that I decided to make a career out of working with them. Nothing compares to the satisfaction of engaging children. But for years my career had unfolded far

away from the conflict in Israel/Palestine. I thought it was time, now, to bring these two parts of my life together—to merge teaching and activism.

Teaching karate to children means providing them with structure, discipline, and high expectations. When taught correctly, karate will also instill an independent spirit. Thus another form of defiance opened up to me: I would teach Palestinian children karate.

Plus I wanted to see how Israeli control over Palestinian life had affected children. I wanted to see and interact with kids in the West Bank, in places like the Deheishe Refugee Camp, or the town of Anata, where playgrounds and parks were scarce. I wanted to hear Palestinian children, listen to them, and to get an idea of how they viewed their lives and their future. So I looked for opportunities to teach karate in those very places.

It was the summer of 2007 when my sister Nurit had actually come up with the idea for me to teach in Palestine. Wael Salame, a good friend who we knew through Combatants for Peace, had boys who practiced at a Tae Kwon Do club in Anata, just north of Jerusalem, and Nurit told him about me and between them they set the whole thing up.

The truth is, I had no idea what to expect. I knew for a fact that Palestinian children had a great burden to carry, far more than children should have: fathers or brothers locked up in Israeli prisons usually with no visitors allowed, family members killed in the conflict, neighbors and friends whose homes were lost to settlement activity or destroyed by the army. Not to mention irregular supplies of water and electricity, severe travel restrictions that impacted their ability to reach school every morning, night raids by Israeli soldiers who stormed their homes at all hours. And the list goes on. One could only assume that their parents and teachers, who loved and cared for them, had given them the tools to cope with their impossible and abnormal surroundings.

I took Eitan, who was 13 at the time, and Doron, who was 11, and their cousin Yigal, who was 14, along to Anata to practice as well. When we arrived at the Tae Kwon Do club, we received a warm welcome from Wissam, the instructor, and there were more than 50 kids, all lined up and ready for practice. There were boys and girls practicing together, and they were completely comfortable with each other, which I am always happy to see. While there is a stereotype that karate is a boys’ activity, girls usually really enjoy and excel at it, and I always encourage girls and women to take classes alongside boys and men. The students at the Anata club were serious, polite, and eager to learn, all signs of a good martial arts school.

Practice went on for about an hour and a half. After practice, we all relaxed for a while and talked. Eitan began chatting with one of the kids. I heard him ask: “Do you like going to the beach?” Coming from a southern California beach town, it was a natural thing for him to wonder.

The boy took Eitan to the window and showed him the separation wall being built just outside the gym where the class took place. Even though Anata is part of

Jerusalem, the wall and the checkpoint prevent its residents from traveling freely. “We can’t go to the beach,” he said. “We are not allowed.”

When practice was over we had dinner in Anata at Wael’s home, and when we were done the adults had coffee and the kids played soccer on the small balcony adjacent to the house, because there was nowhere outside for them to play. On the way home, at the Anata checkpoint, my sons noticed a Palestinian boy not much older than them being taken in by the soldiers.

Doron, frightened by what he saw, asked, “What did he do?”

“I am not sure.” I was not able to reassure him.

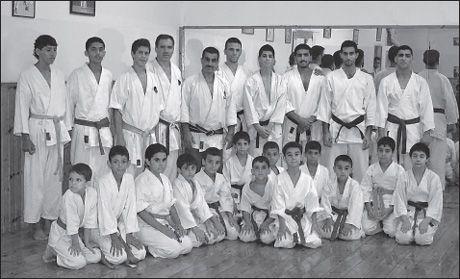

Jamal introduced me to a karate club in Ramallah that is run by a friend of his named Nidal. Nidal has been practicing and teaching for many years and has built a fine student body and a very nice, traditional Japanese dojo. I have visited there several times and taught classes and Nidal, Jamal, and I always have a good time together. In the summer of 2010 I went to Nidal’s karate school with Doron, and Nurit came along, too, to watch. The class was full, and it was extremely hot. As the class progressed, the heat became unbearable, and with it my thirst. I was thinking of asking Nurit for a water bottle when I remembered then that this was the month of Ramadan.

During this month Muslims refrain from eating or drinking from sunrise to sundown. It was about four in the afternoon and the fast was not going to be broken until seven that evening. I looked at Doron and I could see his mouth was dry

too. The students did not show any signs of weakness, and they were all cheerful and completely focused on karate. Still, their faces were red, and they were hot and sweaty, so I stopped the class for a moment and asked them to sit down.

Doron, standing third from left and I standing next to him, with Sensei Nidal at the karate club in Ramallah

“

Meen Minkum Sayyim?

” I said. Who among you is fasting?

I could see that even Nidal was surprised when they all raised their hands.

“Wow! You guys are very special kids. There aren’t a lot of places in the world where kids would come to karate class and work so hard in such heat without food or water. Especially water!”

I looked at Doron again and I saw that he knew what it meant when all the kids raised their hands: that we, too, were not going to drink till sundown.

During class I gave the kids the same talks I do when I teach at my own karate school in the U.S., but with a little extra: always be respectful, believe in yourself, use your head. I also mention the fact that I can go to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv and travel freely in this country, but they cannot.

“This is your country, your home, and you should be allowed to travel freely as I do, as every Israeli child does. Karate teaches us to overcome insurmountable obstacles, and you will find a way out of the injustice in which you live, and do it without having to sacrifice your young lives. You will have the freedom to live, study, work, and travel anywhere you like. Just remember to believe in your abilities and don’t be afraid.”

There is always silence when I say these things. The first time I said something like this to Palestinian kids, it was actually not at a karate class. I was at Jamal’s house. His older daughter mentioned that she wanted to attend dental school, and we talked about languages. I said that I thought it would be useful for her to be able to converse freely in Hebrew and English so that she could treat patients in cities around the country. “The occupation will not last forever, and you will be able to practice in Haifa or Tel Aviv and so Hebrew would be useful when you treat Israeli patients.” She looked very surprised at my assumption that the end was in sight. “

Insha’ Allah, Insha’ Allah,”

she said. God willing. And her mother repeated, “Insha’ Allah.”

I do believe that Israelis and Palestinians will live free side by side one day. And even if we become two separate states, why could a Palestinian doctor not practice in Israel, or vice versa? I felt this was an important thing to say in front of Palestinian children. I wanted to state with complete certainty that things will change for the better and to encourage them to believe it and to act in accordance with this belief. The overwhelming force of the Israeli army can make anyone feel hopeless. And the fact that the world does little for Palestinians can lead to a sense of helplessness. I have always thought that change will come from the bottom up— not from any outside source, but from these children. But someone has to paint the picture, and so I do that whenever I can.

In late 2010, I called my friend Mazen Faraj from the U.S. and I told him that I wanted to visit Deheishe Refugee Camp near Bethlehem. Mazen was born and

raised in Deheishe, and he still lives there with his family. I asked if he thought I could teach karate there. Mazen did not hesitate to endorse the idea and quickly moved to make arrangements for me.

Once again, I left my cozy existence in Coronado and traveled to my troubled homeland. I called Mazen again from Jerusalem, and we decided to meet by the Everest Hotel in Beit Jala where the Palestinian branch of the Bereaved Families Forum has their office.

It was a sunny December afternoon and I sat out on the balcony waiting for Mazen. The office is located on a hill, and so I had a full view of the occupation. Israeli military vehicles, covered in protective wiring, drove fast and nervously with their blue lights flashing. I could hear the loudspeakers from the army base nearby and police sirens in the distance. And I could hear the sound of new homes going up in the Israeli settlement of Har Gilo.

Mazen arrived a few minutes after I did. I spent most of the afternoon sitting on the porch talking with him. He had set up a visit to the Deheishe Refugee Camp for me, and I was going to teach karate there over the next few days. Mazen is energetic, and he knows how to get things organized.

Sitting on the porch—while he lit one cigarette with another and I sipped Arabic coffee—we went from small talk to politics and then to his story and the story of his family. His older brothers had participated in the first Intifada and sat in jail; they are all principled men who hold respectable positions. Mazen himself belonged to the PFLP and had been arrested by Israel for that reason. He told me of the torture and beatings he endured during his interrogation.

“What kept me from breaking during the interrogation and torture was the knowledge that, like my brothers before me, it would be known that I did not break during the interrogations and I did not talk.”

He lit another cigarette, cursed in Arabic, and then said, “Not a night goes by without nightmares from the torture I received at the hands of the Israelis.”