The General and the Jaguar (16 page)

Read The General and the Jaguar Online

Authors: Eileen Welsome

At fifteen minutes before midnight, E. A. Van Camp, one of the fastest press telegraphers in the United States, stepped down

from the westbound train from El Paso. He walked quickly through the empty streets to a small out-of-the-way hotel, where

his friend, George Seese, the Associated Press reporter, was staying. Seese, duly chastised by his bureau chief in New York,

was still covering the Pancho Villa story. Earlier in the week, he had slipped away from his hard-drinking newspaper buddies

back in El Paso and made his way to Columbus. Accompanying him was a charming new wife, whom he had married in Deming only

eleven days earlier. (Her newlywed bliss would be shattered when she learned the flamboyant newspaperman had another wife

and four children back in Los Angeles.)

Also getting off the midnight train were John P. Lucas and Horace Stringfellow Jr., both West Point graduates and second lieutenants

who had been in El Paso at a polo tournament. The tournament had ended earlier that afternoon and they decided to catch the

train back to Columbus. The El Paso papers had been filled with stories about Villa and the two young officers, Stringfellow

would later write, “were hoping to get in the aftermath of some raid on a border ranch, although of course we could not even

have imagined an attack on Columbus itself.”

First Lieutenant James Castleman, the officer of the day, had greeted Lucas and Stringfellow as they stepped down from the

train. Castleman was relaxed and mentioned nothing to them about Villa. As Lieutenant Lucas walked to the house where he lived,

the unredeemed ugliness of Columbus once again assaulted his senses: “A cluster of adobe houses, a hotel, a few stores and

streets knee deep in sand combined with the cactus, mesquite and rattle snakes of the surrounding desert were enough to present

a picture horrible to the eyes. . . .”

Lucas commanded the Machine Gun Troop, a relatively new unit in the U.S. cavalry, which, in the case of the Thirteenth Regiment,

consisted of misfits and troublemakers and outcasts that no one else wanted. Lucas had taken them all under his wing. He knew

they were brave men and could think of no better soldiers to have at his side during a fight.

Upon arriving at the small house he shared with Second Lieutenant Clarence C. Benson, who was on patrol along the border,

Lucas picked up his revolver and noticed that it was empty. Though the hour was late and he was exhausted, he proceeded to

move the boxes that were piled up in front of their trunk room in order to get at his extra ammunition. He sat down on his

cot and pushed the bullets into the chamber, wondering why he was going to the extra trouble. The night was calm and still

and he had seen nothing out of the ordinary to alarm him. After reloading his weapon, he lay down on his hard bed and fell

immediately into a deep sleep.

Castleman returned to his shack, which was on the east side of the road that ran south into Mexico. Knowing that he would

have to make another inspection at four o’clock, he continued reading deep into the night. Soon his was the only light burning

in the unbroken darkness.

The Fiddler Plays

A

S

S

USAN

M

OORE

was drifting off to sleep, the Mexican soldiers were being kicked awake by their

jefes.

They rose instantly, blinking back the dreams and the fatigue-induced hallucinations that danced at the corners of their

vision. In silence, they ate their tortillas and fetched the ponies. The little animals opened their mouths docilely as the

metal bits were shoved between their teeth and the girth straps tightened. No mediating layer of moisture existed between

the troops and the night sky and the air was very cold. The soldiers stamped their feet and shook the numbness from their

hands. Most had no idea where they were going, but the knowledge of an impending battle had spread among them. Some sang mournful

songs; others developed mysterious flus and stomachaches. The devout murmured prayers to the Virgin of Guadalupe and the soldiers

who were resigned to their fate composed farewell messages for their families. Only the half-witted fiddler, Juan Alarconcon,

seemed himself. He longed to put his bow to his fiddle in the shining dark and strike up an inspiring rendition of “La Cucaracha,”

the División del Norte’s old battle song, but was told that he would be shot if he did so.

Maud noticed that Pancho Villa had changed into a uniform and was riding a spirited paint stallion that had been taken from

the Palomas ranch. Earlier that day, Nicolás Fernández had approached her with a rifle. Maud felt certain her time had come,

but instead of killing her, he wanted her to take the rifle and use it against her countrymen. Maud refused, saying the first

thing she would do was shoot him and every other officer. He laughed, saying he believed her, and walked away.

Whatever doubts Villa may have harbored about the attack, he didn’t share them with the rank and file. Bunk Spencer, the African-American

hostage, would later tell newspaper reporters that Villa gave a demented, rage-filled speech. “He told the men that ‘gringos’

were to blame for the conditions in Mexico, and abused Americans with every profane word he knew because the Carranza soldiers

were allowed to go through the United States to reach Agua Prieta, where Villa was defeated. He didn’t talk very long, but

before he got through, the men were crying and swearing and shrieking. Several of them got down on the ground and beat the

earth with their hands.”

The column began marching slowly across the country in a northerly direction, retaining the same formation that they had on

the long journey up from Mexico. Two small groups of soldiers were positioned at different points near the border to cover

Villa’s retreat, leaving approximately 450 men in the main body. At some point prior to the attack, fences had been cut along

the border and the railroad’s right-of-way to facilitate the Mexicans’ escape from the United States.

When they reached the international boundary line, about two miles west of Columbus, Maud saw five lights. Two appeared to

be moving toward each other and greatly frightened some of the soldiers, who considered them bad omens. They soon realized

they were merely the headlights of trains moving in opposite directions. The three stationary lights were fires to help guide

their entry into town.

Crossing the border, they rode north up a deep arroyo that hid them from anyone who might be watching. Near a railroad bridge

that spanned the arroyo, they paused for a few minutes while a train passed by. “We were finally so close to the tracks that

when the train passed, we were able to see the passengers in the coaches,” Maud remembered.

They then resumed their slow, stealthy march eastward across the flat open country until they reached a point roughly a mile

and a quarter west of a small rounded knoll known as Cootes Hill. It was the only hill of any size in the Columbus area and

allowed them to prepare for the attack undetected. It was now about three o’clock on the morning of March 9, Villa’s favorite

time for attack. He and his officers reviewed the troops and picked out the men who would participate and those who would

be left behind to hold the horses. As usual, they were short of ammunition, so the horse holders were ordered to turn their

bullets over to the selected raiders. (The Mexican troops were notoriously bad shots; few had marksmanship training or knew

how to use the sights on their rifles.)

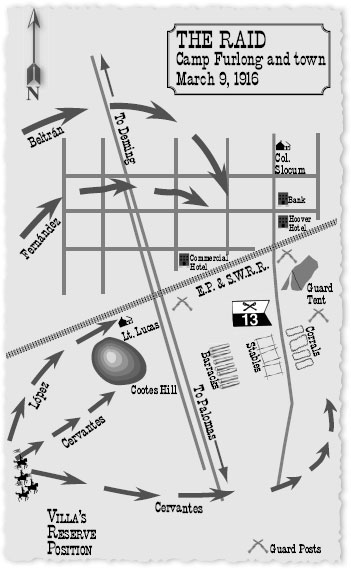

The plan called for a three-pronged assault, with the Mexican troops converging on Camp Furlong and the town simultaneously

from the west, north, and east. The right wing, composed of Candelario Cervantes’s troops and half of Villa’s personal escort,

would occupy the knoll and continue forward into the military encampment. Some of these soldiers were to swing counterclockwise

around the military post and take the horses stabled on the east side of the camp. Pablo López and his men would make up the

center wing and use the railroad tracks to guide them into the town. The left wing, commanded by Nicolás Fernández and Francisco

Beltrán, was to circle around the town and come down from the north and northwest.

In one of the last orders of business, Villa announced that Colonel Nicolás Fernández had been promoted to general. Then he

gave the order for the men to dismount and advance on foot.

Vámonos, amigos!

Viva Villa!

Viva México!

Matemos a los gringos!

Hundreds of armed soldiers streamed through bushes toward town. Soon the percussive explosions of the Mexicans’ Mausers alternated

with the pop-pop of the cavalry troopers’ Springfield rifles. The high-pitched Mexican bugles dueled with the lower-pitched

cavalry bugles, which were frantically rallying the American soldiers to arms. From somewhere near the top of the knoll came

the first ghostly strains of “La Cucaracha.” And a few blocks to the northeast, Colonel Slocum bolted up in his bed. “My God,

we are attacked!”

L

IEUTENANT

L

UCAS

was awakened by the creak of leather and crept to the window, where he saw men riding toward the military camp. He recognized

the intruders as Villistas by the hats they were wearing and judged that he was completely surrounded. Lucas grabbed up his

pistol, thankful now that he had taken the time to load it, and positioned himself in the middle of the room, where he would

have ample view of the door. He was sure he would be killed but if that was to be his fate, he figured that he would take

a few of the Mexicans with him.

Before they had time to enter Lieutenant Lucas’s house, Fred Griffin, the young sentry posted in front of headquarters, spotted

the invaders. He was standing perhaps 250 feet east of Lucas’s house and called for them to halt. The Mexicans charged toward

Griffin, firing. Shot in the stomach, chest, and arm, Griffin managed to squeeze off a few rounds, killing two or three raiders

before he collapsed. The diversion saved Lucas’s life, enabling him to get out of his house. He dashed past the headquarters

building, where Griffin lay dying, and ran to the barracks, where he told the acting first sergeant to turn out his men and

have them meet him at the guard tent, where the machine guns were kept. On his way to the tent, an armed Mexican suddenly

appeared in front of him. Both men fired. When the smoke and noise died away, it was Lucas—one of the poorest shots in the

regiment—who was still standing.

When he reached the guard tent, Lucas saw another young sentry sprawled across the door. He stepped over the soldier and fumbled

in the dark to open the cabinet where the French-made Benét-Mercié machine guns were kept. The guns were in great demand on

the black market because Mexican troops would pay as much as five or six hundred dollars apiece for them. One had disappeared

from the Thirteenth Cavalry’s arsenal a few years earlier, and as a consequence they were always kept under lock and key.

Weighing only thirty pounds, they were easy to carry, but difficult to feed in the darkness. Lucas and several of his men

grabbed one anyway and set it up near the stables. Lucas fed the clip of bullets into the metal slot while a corporal acted

as gunner. Almost immediately, the weapon seized up. Lucas and his men swore violently, picked up the gun, and raced toward

the hospital, where they hoped to repair the weapon behind the building’s bulletproof adobe walls.

While Lucas was getting his machine guns and troops deployed, Lieutenant Castleman was running toward the barracks to rouse

his men. It just so happened that the soldiers had recently been drilled in what to do in the event of a surprise attack and

were already falling in. With about twenty-five men from Troop F, Castleman proceeded north toward the town, where his first

priority was to check on his wife and make sure she was safe. As they advanced, the Mexicans poured heavy gunfire on them

and the bright yellow flashes lit up the terrain with a surreal beauty. The Americans dropped to the ground and returned fire.

“On account of the darkness,” wrote a young sergeant named Michael Fody, “it was impossible to distinguish anyone, and for

a moment I was under the impression that we were being fired on by our own regiment, who had preceded us to the scene. The

feeling was indescribable and when I heard Mexican voices opposite us you can imagine my relief.”

Incredibly, none of Castleman’s men were hit in the fusillade and they stood and began making their way north again. As they

were crossing the railroad tracks, Private Jesse P. Taylor was shot in the leg. Fody told him to lie down and be quiet, promising

that they would pick him up later. Ten yards farther, another private tripped, setting off his gun and giving himself a nosebleed,

as well as alerting the attackers to their location. More gunfire rained down on them. Castleman’s men again dropped to the

ground and returned the volley. When the onslaught lessened, they stood and advanced. “We made about four stands in about

five hundred yards,” remembered Fody. “Private Thomas Butler was hit during the second stand but would not give up and went

on with us until he was hit five distinct times, the last one proving fatal.”