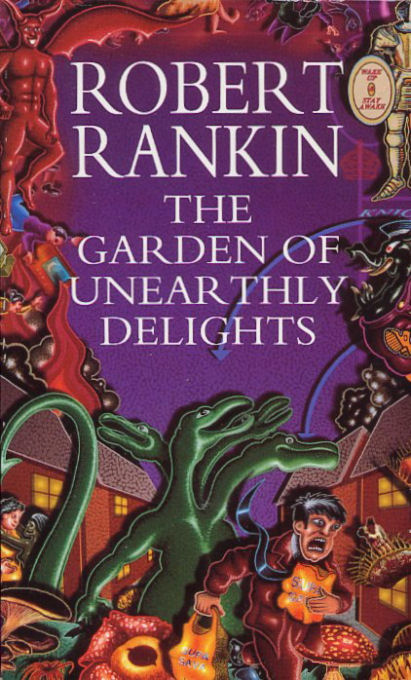

The Garden of Unearthly Delights

Read The Garden of Unearthly Delights Online

Authors: Robert Rankin

The Garden of Unearthly Delights

Robert Rankin

For

my dear little white-haired old mother

who

can flick past the rude bits

love

and laughs

and

Rock

‘n’ Roll

Oh

yeah!

1

‘Rock ‘n’ Roll,’ said

Maxwell Karrien, as he opened the official-looking envelope. ‘This is something

of a great surprise.

He

called out to his wife of some years’ standing. ‘Wife,’ called he, ‘come look

at this.’

‘Whatever

is it, dear?’ the dear one answered. Maxwell scratched his head. ‘It would seem

that I have been awarded The Queen’s Award for Industry award.’

‘The

saints preserve us all,’ said his voluptuous spouse, her bosoms entering the

sitting-room before her like a dead heat in a Zeppelin race. ‘And you never

having done a day’s work in your life.’

‘‘Tis

true,’ said Maxwell, giving his head another scratch for luck. ‘And it would

appear that I have dandruff also.’

‘All in

one day.’ His wife smoothed down her satin housecoat and shuffled her pompommed

slipperettes.

Maxwell

dropped into his favourite armchair. ‘I suppose I shall now be called upon to

officiate at Council functions, open fetes and jumble sales, kiss babies and

give talks at the Women’s Institute.’

‘I

never knew dandruff made one so important,’ said his wife, whose sarcasm had

got her into trouble on more than one occasion.

Maxwell

kicked her playfully in the ankle. ‘Limp off and make my breakfast,’ he

suggested. ‘I have some serious thinking to do.’

‘Your

day for the use of the family brain cell then, is it?’ whispered his wife,

between gritted teeth, as smiling sweetly she hobbled away towards the unfitted

kitchen.

It was

not

a marriage made in Heaven.

What

with

her

hating

him

and

him

hating

her.

And

everything.

Maxwell

took his tin and liquorice papers, rolled himself a ciggy and composed his

handsome features into a look of grave concern. ‘This must be a mistake,’ he

told himself.

‘It is

probably meant for Mr Camp next door,’ he continued.

‘That

would be it,’ he concluded.

But

upon once more examining the gilt-edged certificate, these thoughts were forced

to flee. There were the letters which formed his name. Bold as brass in

copperplate.

‘Papyrophobia,’

said the fearful man. ‘This is

not

Rock ‘n’ Roll.’

After a breakfast of egg,

bacon, sausage, baked beans and a fried slice that the not-so-dear one had

stubbed her cigarette out on, washed down with two cups of Earl Grey, Maxwell

decided that he would take his certificate around to Father Moity at St Joan’s

to get an unbiased opinion.

For he

reasoned thus: if I ask Duck-Barry or any of the lads at The Shrunken Head,

they will say, ‘Well done, Maxwell, get the drinks in.’

And if

I ask the man in the cardy at the Job Centre, he will say, ‘Queen’s Award for

Industry award, eh? Then we’re stopping your dole money, mate.’

And if

I ask at the Police Station, the policemen will become embittered that I

received it rather than they and they will smite me with their truncheons, as

they do every time they see me anyway.

And so

by such reasoning,

ten o’clock

of the morning hour found Maxwell in a confessional box, his Queen’s Award award

upon his knee and his chin upon his chest.

To the

eastward side of the grim little grille, Father Moity seated himself, mumbled

holy words and pecked at his crucifix.

‘Spit

it out,’ said he.

‘Bless

me, Father, for I have sinned, it has been seventeen years since my last

confession.’

Father

Moity put on his most professional face (which he kept in a jar by the door)

and scratched at his old white head. This was going to be a baddie, he thought,

and, I seem to have dandruff, he discovered.

‘It all

began this morning,’ said Maxwell in a reverent tone.

‘You

have not been to confession for seventeen years and you have the nerve to tell

me that it all began

this morning?’

The

priest coughed into his cassock and marked out a cross on his chest.

‘I have

been awarded The Queen’s Award for Industry award (award),’ said Maxwell.

‘Blessed

be,’ said the priest. ‘And is it for seventeen years of sinlessness that this

award has been awarded?’

‘Sinless

towards industry,’ said Maxwell. ‘For I have never done an honest day’s work in

my life.’

‘Then

isn’t it a wonderful world that we’re living in today and I don’t think that

our likes will ever be here again,’ said the priest, who feared not the sin of

plagiarism.

‘I was

hoping for some advice, Father,’ came the voice of Maxwell to his ears.

‘Advice

is it you’re wanting? Well, here’s some now for you to be going on with.’ The

priest coughed once again.

‘I

should

cough?’

asked Maxwell, somewhat bewildered. ‘Is that the advice

you’re offering?’

‘Not a

bit of it. I recently had a bad asthmatic attack.’

‘I’m

sorry to hear that.’

‘Indeed,’

said the priest. ‘Three asthmatics attacked me outside Budgen’s. Was my own

fault, I should have heard them lying in wait.’

Maxwell

scratched once more at his head. His dandruff had cleared up, at least. ‘About

the advice,’ he adventured.

‘Lead

by example,’ said the priest. ‘By your deeds let others know you. These Queen’s

Award award awards are not handed out willy-nilly to any old Tom, Dick or

Harry. It has probably arrived in the wrong post, for some service to industry

that you have yet to perform.’

‘You

think that might be it then?’

‘Seems

obvious to me, my son.’

‘Well

thank you very much, Father.’ Maxwell rose to take his leave.

‘Will

you not be after confessing any of your sins then?’ asked the priest, in a

sing-song Irishy kind of a way.

‘No, I

think not.’

‘Then

go with God, you capitalist bastard.’

‘Thank

you, Father.’

‘Bless

you, my son.’

Maxwell slouched from the

church and took to plodding homeward, the heavy weight of his potential

responsibilities pressing down upon his shoulders. As he crossed the canal

bridge, he considered tossing his Queen’s Award award into the murky depths.

But on a second thought he didn’t and continued on his way. On the corner of

Maxwell’s street stood the

Tengo Na Minchia Tanta

Café. Right where it

had always been. Maxwell stepped inside to take some beverage and think things

through.

The new

girl behind the counter knew Maxwell by sight alone. ‘What would you like,

sir?’ she enquired, and there was more heaving sensuousness, more unabashed

eroticism, more blatant vibrating sexuality in those few words, than could ever

really happen in real life.

‘Pardon?’

asked Maxwell, whose life was real enough to him.

‘Tea or

coffee, sir?’

‘Coffee,

black, no sugar, please.’

The new

girl liked male customers who took their coffee black with no sugar. Very

manly, she thought. Very

machismo.

Those

who knew Maxwell through introduction rather than by sight alone, might well

have scoffed at this, for Maxwell was no great man for the ladies.

The

Maxwell these folk knew was a decent enough chap on the whole, but with that

said considered by some rather

dull,

if not

stupid.

The

looks of himself were fine enough. Nearing the magic six feet in his height and

in the middle of his twenties, he was gaunt of frame and square about the

shoulders. Well favoured in the face department, with kind grey eyes, a happy

mouth and a nose like a friendly arrow head. His hair was black and well quiffed

back and his mood was, in general, hearty. But Maxwell did have his foibles,

his choice of dress being one such. Maxwell held in high favour the

America

of the nineteen fifties, the

America of Wurlitzer Jukeboxes and Chevrolet Impalas and Danny and the Juniors.

And this holding in high favour had a tendency to reflect itself in his day

wear.

Maxwell

sported Oxfam zoot suits, slim Jim ties and bowling shirts. Shirts whose

collars had no ‘stand-up’, large, substantial, crepe-soled boots. And as those

who have ever sought to make a statement of their individuality through their

choice of apparel will readily affirm, eccentricity of dress rarely fares well

in societies where conformity is considered the standard by which others judge

you.

Those

who fail to conform are at best mocked and ridiculed, at worst, ostracized or

injured.

If you

are wealthy you can do as you damn well please. But if you are not, and Maxwell

most definitely was

not,

then

pleasing

is something you must do

for other people.

The

rich can dress

up

to impress, the poor must dress

down

to

survive. Maxwell dressed as he pleased, Maxwell was poor, hence to the world

that Maxwell inhabited, Maxwell’s appearance was ‘stupid’.

And it

had to be said, his habits did not exactly aid his cause (if cause he had,

which actually he didn’t). When not in the company of his beautiful wife, whom

he had married in haste to repent about at leisure, Maxwell could, like as not,

be found in the public library.

Here he

passed away much of his life, deeply engrossed in the science fantasy novels

of P. P. Penrose

[1]

,

thrilling to the daring exploits of Sir John Rimmer, Dr Harney and Danbury

Collins (the psychic youth himself) as they locked in mystical conflict with

the evil Count Waldeck.

Maxwell

seriously ‘got into’ these books. They were escapism nonpareil. And though, to

the outward world, his dress code offended many and his conversation was at

best uninspired, in that personal inner world of fantasy fiction, he was up

there with the best of them, often solving some inexplicable conundrum pages before

Sir John and his loyal companions caught on.

So this

was the Maxwell that those who knew him knew. Dull, said some, and stupid,

others, and Maxwell alone knew himself.

Maxwell

paid for his coffee, took it to a window seat and sat down miserably.

The new

girl behind the counter smiled him a smile. Here is a fellow, she thought, who

needs a shoulder, nay a breast, to rest his weary head upon. A handsome fellow.

A shame about the stupid clothes though.

Sandy

the sandy-haired manager stood at the new girl’s shoulder. Making one of his

rare appearances at the

Tengo Na Minchia Tanta,

he had been examining

the till roll upon Maxwell’s arrival, and now felt it the moment to confront

the new girl with his findings. ‘Surely,’ said

Sandy

, ‘I spy a deviation here.’

The new

girl’s eyes left Maxwell, toured the café, took in the window view and finally

met up with those of her employer.

‘You

what?’ she asked.

‘The

cash in the register and the takings logged upon the till roll vary to the tune

of twenty-three pounds, two and threepence,’ said the manager called

Sandy

.

‘What

is that in new pee?’