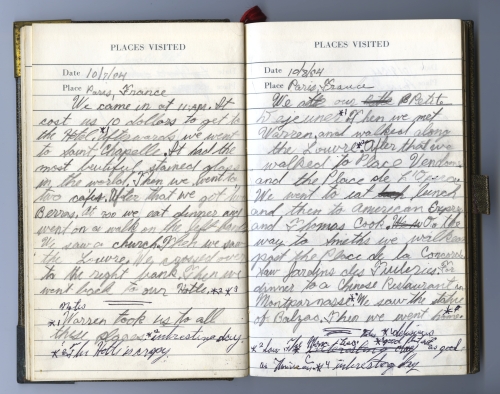

The Game Player (31 page)

He believed me, I thought with relief. I couldn't remember ever having succeeded in lying to him before. I walked gingerly to the other side of the couch, as if loud steps could disturb a smooth digestion of my falsehood. Brian's eyes were closed, but he spoke the moment my eyes were on him in a spooky clairvoyance. “I'm ready to sleep now,” he said. “Could I do it here?”

“Absolutely, I'll get you sheets and blankets.”

“That'll be super. Can you come to the funeral and other grotesque ceremonies with me?”

“Definitely.”

“Thank you.” I left him, and told Karen he was fine, while I got the things for the couch. But when I returned he was fast asleep. He was lying flat on his back, his hands demurely clasped over his stomach, a picture of the perfect rest, the eternal sleep. I had a silly thoughtâhe's going to be well from now on, he's purged. I put the blanket over him and tried to stuff the pillow next to his head. He stirred enough for me to squeeze it in.

Karen was desperate to know what had gone on, especially since she had heard his sobs. She asked what we had talked about; I could only stare at her out of the emptiness of my feelings. “You don't want to talk about it?” she added meekly.

“There's nothing to tell.” The irritation in my voice surprised me. “He said he hated his father sinceâoh, God, I don't know, since childhood.” I looked at her, my face heavy with displeasure, and had to force myself to go on. “Getting A's, going to Yale, to Harvard, all of it! just because his father promised him money.” I watched her sit up and reach for a cigarette, not taking her eyes off me as if in fear of missing a key word. I sighed and let myself sit on the bed. “He doesn't care about law or about any of the things he studied. He did it because his father demanded that he do so or Brian wouldn't get any money.” I paused and watched her. After the silence had become uncomfortable, she said, “That's horrible.”

“Why didn't he rebel? you might ask. Because he wanted to prove to Daddy that nothing was too difficult. He could beat us at all those games because winning at them, beating us, was meaningless to him. He had no personal investment.”

“That's interestingâ”

“It's the end of our friendship,” I said quickly to interrupt any attempt to analyze the revelations.

“What?”

“I can't accept it!” My anger startled her.

“But,” she stammered for a moment and continued timidly, “why would he lie?”

“I don't

mean

he's lying.”

“Don't be angry at me,” she said with a patient look. “I just mean his story makes sense.”

I said nothing. I looked away because my eyes felt bloated and I feared they would betray me. She touched my arm. “You'll still be friends,” she said softly.

When she had fallen back to sleep, leaving me alone, in the light of dawn, with the blue haze of my cigarette smoke trailing slowly to the ceiling, I thought of all the guesses and judgments I had heard over the years about Brian, or people like him. I was amazed that successful people, beautiful people, inspired so much analysis, especially since all of it was an attempt to discover their weakness, the tragedy that makes their perfection undesirable. To discover his flaw had been the suspense of our friendship. I had waited for this night, I realized, since that football game.

I had wanted to learn that he would eventually lose. I had wanted, when that no longer seemed possible, to think he was the product of a monstrous society. I could believe that, but then so was I. I had wanted to learn that his winning didn't make him happy. But nothing did, it seemed to me, except trying to win. And that was even more of a disappointment: trying to win is meaner, after all, than succeeding. His real feelings, that his life was empty but for the hatred of his father, were unbelievable, unacceptable.

He called me his brother, and I assume that wasn't flattery, but after the week of his father's death, while I accompanied him to the necessary ceremonies, I said good-by as he left for Boston, not wanting to know him anymore. I was sure that, with the million or so he had inherited from Mr. Stoppard, Brian would go on, a computer whose objective its programmer's death wouldn't abort, and I didn't want to watch my hero win victories with tactics he loathed; victories achieved only to avoid boredom and hopelessness.

My friends often complain that there are no heroes to cheer on; occasionally I will read an article about the danger of contemporary movies and television providing no examples for children to follow; and I often read in amazement the little facts about people in junky magazines that tell us So-and-so, a Nobel prize winner, still dreams of fighting Indians with John Wayne. I was a fool to think I wanted to know the truth about Brian Stoppard. Sometimes, while reminiscing with others about my childhood, I catch myself talking with delight about his activities. I have to stop then, and close my eyes for a moment, to hold back the yell of anguish that needs to escape. For now, I am doomed to live like the rest of you, in a godless universe.

A Biography of Rafael Yglesias

Rafael Yglesias (b. 1954) is a master American storyteller whose career began with the publication of his first novel at seventeen. Through four decades of writing, Yglesias has produced numerous highly acclaimed novels and screenplays, and his fiction is distinguished by its clear-eyed realism and keen insight into human behavior. His books range in style and scope from novels of ideas, psychological thrillers, and biting satires, to self-portraits and portraits of New York society.

Yglesias was born and raised in Washington Heights, a working-class neighborhood in northern Manhattan. Both his parents were writers. His father, Jose, was the son of Cuban and Spanish parents and wrote articles for the

New Yorker

, the

New York Times

, and the

Daily Worker

, as well as novels. His mother, Helen, was the daughter of Yiddish-speaking Russian and Polish immigrants and worked as literary editor of the

Nation

. Rafael was educated mainly at public schools, but the Yglesiases did send him to the prestigious Horace Mann School for three years. Inspired by his parents' burgeoning literary careers, Rafael left school in the tenth grade in order to finish his first book. The largely autobiographical

Hide Fox, and All After

(1972) is the story of a bright young student who drops out of private school against his parents' wishes to pursue his artistic ambitions.

Many of Yglesias's subsequent novels would also draw heavily from his own life experiences. Yglesias wrote

The Work Is Innocent

(1976), a novel that candidly examines the pressures of youthful literary success, in his early twenties.

Hot Properties

(1986) follows the up-and-down fortunes of young literary upstarts drawn to New York's entertainment and media worlds. In 1977, Yglesias married artist Margaret Joskow and the couple had two sons: Matthew, now a renowned political pundit and blogger, and Nicholas, a science-fiction writer. Yglesias's experiences as a parent in Manhattan would help shape

Only Children

(1988), a novel about wealthy and ambitious new parents in the city. Margaret would later battle cancer, which she died from in 2004. Yglesias chronicled their relationship in the loving, honest, and unsparing

A Happy Marriage

(2009).

After marrying Joskow, Ylgesias took nearly a decade away from writing novels to dedicate himself to family life. During this break from book-writing, Yglesias began producing screenplays. He would eventually have great success adapting his novel

Fearless

(1992), a story of trauma and recovery, into a critically acclaimed motion picture starring Jeff Bridges and Rosie Perez. Other notable screenplays and adaptations include

From Hell

,

Les Misérables

, and

Death and the Maiden

. He has collaborated with such directors as Roman Polanski and the Hughes brothers.

A lifelong New Yorker, Yglesias's eye for city lifeâambition, privilege, class struggle, and the clash of culturesâinforms much of his work. Psychiatrists and psychoanalysts are often primary characters in Yglesias's narratives, and titles such as

The Murderer Next Door

(1991) and

Dr. Neruda's Cure for Evil

(1998) draw heavily on the intellectual traditions of psychology.

Yglesias lives in New York's Upper East Side.

Yglesias with Tamar Cole, his half-sister from his mother's first marriage, around 1955. He was raised with Tamar and his half-brother, Lewis.

Yglesias sits atop his half-brother Lewis Cole's shoulders around 1956. As adults, Yglesias and Cole worked together writing screenplays for ten years. All of them were sold, but none were ultimately made.

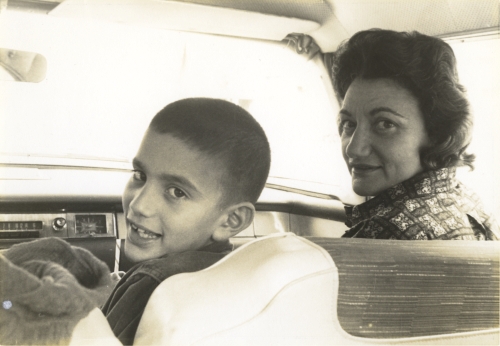

Yglesias at age ten, in a car with his mother in his father's hometown of Ybor City in Tampa, Florida. Around this time, Yglesias lived in Spain for a year, an experience that proved formative in his young life.

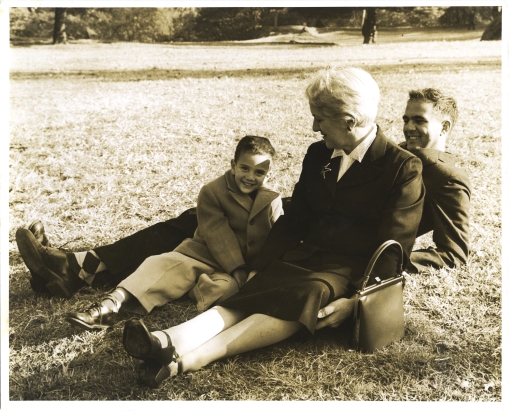

Georgia Yglesias, Rafael's paternal grandmother, is shown here relaxing in Central Park with Rafael and his father. Yglesias's relationship with his grandmother was an important part of his childhood.