The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (22 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

It was a measure of the new-found confidence of Glasgow that the city hosted its first International Exhibition in 1888 on the stretch of parkland that had earlier provided a place of contemplation for four youngsters who were interested in forming the football club that quickly became known as Rangers. Glaswegians grew giddy at the thought of the cosmopolitan delights of a showcase for their city that would eventually be nicknamed Baghdad on the Kelvin as a result of the eastern influence on the architectural structures that dominated Kelvingrove Park for seven months between May and November. The Glasgow International Exhibition of Science, Art and Industry attracted almost six million visitors in total and was widely recognised as the first truly international exhibition since the great gathering at Crystal Palace in 1851.

In addition to showing off Glasgow’s outstanding achievements as an industrial power and second city of the Empire, the exhibition was also aimed at turning a profit to fund a new gallery and museum at Kelvingrove. Glasgow now boasted such a treasure trove of art and other valuable artefacts there was no longer room to display them at the McLellan Galleries, which was until then its main museum. The art gallery and museum at Kelvingrove opened in time for the next major exhibition in 1901 and still stands today as one of the country’s top tourist attractions in all its refurbished splendour.

In total, there were 2,700 exhibits at the 1888 event, including an electrically illuminated fairy fountain of different colours and a Doulton Fountain, now restored to all its former glory and housed at Glasgow Green. The River Kelvin was even deepened and cleaned and the flow of sewage into its waters stemmed to such an extent there were regular swimming galas. A gondola was brought to Glasgow from Venice especially for the exhibition and two gondoliers, nicknamed Signor Hokey and Signor Pokey, treated visitors to trips up and down the Kelvin. H. and P. McNeil also took the chance to exhibit their wares – at court number two, stand 1241, according to their adverts at the time. Glasgow was letting its hair down, more confident of its place in Britain and the world in general. It was a bold self-assuredness that was being matched at the time by the leaders of Rangers.

The constant creep of industrialisation had long put pressure on land at Kinning Park, the ground Rangers had called their home, if not their own, since 1876. At least twice the Light Blues had fought the threat of eviction from their landlord, but the writing was not so much on the wall as the gable ends of the tenements that began to dominate in the district. The factor, land agents Andersons and Pattison, duly arrived early in the New Year in 1887 and gave Rangers notice to quit their home by 1 March. It was a sad blow, not least because the £60 per annum Rangers paid in rent was considered extremely cheap for the time and the facility. Nevertheless, the move to evict came as no great surprise. In the 1860s Kinning Park was a pretty patch of meadowland and even as late as 1872 the former ground of the Clydesdale Cricket Club sat in rural isolation. However, by 1873 the Clutha Ironworks had been constructed nearby, followed a couple of years later by a depot for the Caledonian Railway Company. By the turn of the 20th century the green grass at Kinning Park would disappear forever and be replaced by a coating of dust from the sawmill of Anderson and Henderson. A move west to the undeveloped lands of Ibrox beckoned.

In the same weekend that Rangers booked their place in the semi-final of the FA Cup against Aston Villa in February 1887, the club’s committee came together and settled on a seven-year lease for a parcel of land of up to six acres at the Copeland (sic) Road end of Paisley Road. They struck a deal with Braby and Company, a building firm from Springburn, to construct a new stadium at a cost of £750, which included a pavilion, a 1,200 capacity stand, an enclosure and a four-lane running track inside a terracing amphitheatre. In addition to the ambitious plans, a playing surface would be laid out 115 yards long by 71 wide and space was even left behind each goal for tennis courts to be introduced at a later stage. The ground, it was claimed, would be little inferior to Hampden Park, then recognised as the best sporting arena in the country.

The Scottish Athletic Journal greeted the decision of the Kinning Park committee to forge ahead with plans for a new ground in February 1887 with glee. It reported: ‘The meeting was most enthusiastic, harmonious in tone and unmistakenly evidenced the deep desire of the Light Blues to take a higher stand in the football arena than they have hitherto done.’1 However, only three years earlier it had foreseen only doom and gloom if Rangers ever moved from Kinning Park. In March 1884 it warned: ‘The Rangers have received notice to quit Kinning Park as the ground is to be immediately built upon. This is a serious blow to the Rangers – one from which they will scarcely recover. It almost certainly means extinction. Dissociate the Light Blues from Kinning Park and the club will soon collapse. One cannot think of the Rangers associated with any other park and grounds situated so near the city as Kinning Park is are not to be had.’2 However, a sub-committee under the guidance of convenor Dan Gillies was formed for the purpose of raising the necessary funds in the spring of 1887. The fears of the Journal would soon prove unfounded.

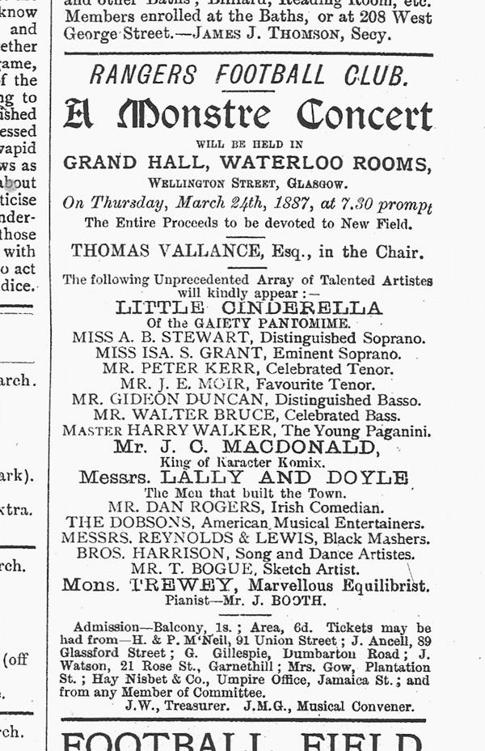

It may not have boasted a line up to match Sunday Night at the London Palladium, but the fundraising concert for the first Ibrox Park at the Waterloo Rooms was a roaring success.

Rangers hoped the bulk of the finance would come from money already at hand and the following season’s gate receipts, but fundraising was also crucial. To that end they organised a benefit concert at the Grand Hall of the Waterloo Rooms in Wellington Street in Glasgow city centre, with Tom Vallance acting as compère. The bill promised acts such as Cinderella, from the Gaiety Theatre pantomime, celebrated tenor Peter Kerr, eminent soprano Isa Grant and Irish comedian Dan Rogers. There was something for everyone, including an American music band, The Dobsons, and even a French equilibrist, Monsieur Trewey, whose trick involved walking along tightropes. Rangers also got the financial balancing act spot on – the night was a complete sell-out, a roaring success. The licence for the Grand Hall was extended to 2am to allow dancing into the night and, with ticket prices of sixpence and a shilling, the club coffers were swollen substantially and concerns eased that the move was a step too far for an organisation that was still just 15 years old.

These days, with its excellent transport links and relative proximity to Glasgow city centre, Ibrox is the perfect home for Rangers geographically, not to mention the strong spiritual links which have been forged with the district for over a century. However, in the 1880s the move to the relative backwater was considered a risk, but it was championed by the club’s honorary secretary Walter Crichton, who foresaw the spread of the booming city further westwards. Glasgow had overtaken Edinburgh in terms of the size of its population as early as 1821 and by the time of the formation of Rangers in 1872 it was home to approximately 500,000 people, which had become almost 660,000 by 1891.

For much of the second half of the 19th century Ibrox was still a rural district – in 1876, fields of corn grew to the very fringes of Clifford Street, which runs parallel between Paisley Road West and the M8 over a century later. An outward sign of the growth and prosperity of the district in the 1870s came with the construction of the original Bellahouston Academy, which still stands today on Paisley Road West near its junction with Edmiston Drive. Districts such as Bellahouston, Dumbreck and parts of Ibrox were home to the well-to-do and they shuddered at the prospect of sending their children across the ever sprawling city for a premier education at Glasgow Academy, situated in the west end, and as a result Bellahouston Academy was formed.

Understandably, given its rural status, the history of Ibrox has tended to be overlooked, certainly in comparison to its near neighbour Govan, once the fifth-largest burgh in Scotland. The oldest recorded mention of the place name now so closely associated with Rangers is Ibrokis, in 1580, and Ybrox in 1590. Indeed, in the 19th century there were still people who lived in and around the district that pronounced it as ‘Eebrox’. The name is believed to come from the Gaelic broc, meaning badger, and I or Y, an old Celtic word for island. According to local lore, a water trough stood just off the head of what is now know as Broomloan Road, with its spring water origins at Bellahouston Hill. The water was so plentiful it occasionally spilled over to join the Powburn, a sluggish stretch of water that meandered through Drumoyne and into the Clyde at Linthouse. A swampy island populated by badgers was formed at the Broomloan Road site where the two stretches of water met, hence Ybrox or Ibrox, the island of the badgers.

In more recent times, the land around Edmiston Drive now associated with the home of Rangers was field and meadowland. There were two large houses on the area now recognised as Bellahouston Park – Bellahouston House, sometimes called Dumbreck House, owned by a famous Govan family, the Rowans. Another estate nearby was known as Ibrox or Ibroxhill and was owned by the Hill family, partners in Hill and Hoggan, the oldest legal firm in the city. Both estates were bought by Glasgow town council in 1895 for £50,000 and within 12 months had been absorbed into the city boundaries, opening their gates as Bellahouston Park.

An historical delve into the origins of the names of Edmiston Drive and Copland Road might also intrigue fans. The former was named after Richard Edmiston, a senior partner in the auctioneer firm J. and R. Edmiston, who operated at West Nile Street for much of the first half of last century. Edmiston’s family home, Ibrox House, was in the shadows of the second Ibrox Park and he was bestowed the honour when the street on which the stadium now stands was first opened. He appeared to have had a philanthropic nature and in 1949 was even named a freeman of Girvan, where he owned a holiday home, after gifting the local museum several paintings by leading artists of the time.

Copland Road was named in the first half of the 19th century after a writer, William Copland, in tribute to the fact that his principal residence was at Dean Park Villa, at the west side of the thoroughfare near its junction with Govan Road. The name of the street was correctly spelled out in maps and journals of the time, but was later changed to Copeland Road after a spelling blunder by builders who were constructing the local Copland Road School. The erroneous letter ‘e’ was allowed to stand unchallenged for much of the first half of the 20th century, but the street name has long since been restored to the original.

If the few residents who lived in the Ibrox district at the time of the Rangers’ arrival had some reservations about their new neighbours, they were probably well founded. A few months before the move, the Scottish Athletic Journal was forced to take Rangers fans to task, not for the first time, for their behaviour at a match, this time against Third Lanark. It reported: ‘There were several of the Kinning Park rowdies at Cathkin on Saturday. Some of them seemed proud of their swearing abilities as they took advantage of every lull in the play to volley forth a few choice oaths which were heard all over the field. It is a pity an example cannot be made of some of these people.’3 Rangers toyed with the idea of taking over the lease of a ground in Strathbungo at a rent of £80 a year and the Journal warned that rents in the area would immediately go through the floor. Perhaps Tom Vallance summed it up best of all at the cake and wine banquet for VIP guests the Wednesday before the official opening of the new Ibrox ground. He addressed the throng and admitted that Kinning Park was not always a place for the faint-hearted. He said, ‘A certain stigma rested on the club owing to their field being in a locality not of the best, while the spectators of the game were not always of the best description, though they were simply such as the locality could afford. I have known very respectable people come to our matches and not renewing their visits but that has all gone and I am sanguine that in our new sphere we will be able to attract to our matches thousands of respectable spectators.’4 His claims proved prophetic, as almost a year after the opening of the first Ibrox Provost Ferguson of Govan admitted there had been initial private misgivings among the burgh’s leading citizens over the arrival of the Light Blues in their district. However, he lavished praise on the Rangers fans, noting there had not been a single arrest in their first season. The Scottish Umpire gushed: ‘It is satisfactory to have such a testimony from the chief magistrate of such a football constituency as Govan as to the law abiding and peaceful character of the crowds which patronise the pastime.’5

Bad behaviour was not restricted to Kinning Park. Indeed, one of the most ugly and unsavoury incidents of the period involved Queen’s Park, following a 3–0 defeat to Preston in the FA Cup in October 1886 at Hampden. There were 14,000 at the game, including 500 from England, and the crowd invaded the field near the end to attack the visitors following a hefty challenge on star player William Harrower by Preston inside-forward Jimmy Ross, younger brother of former Hearts star Nick. Queen’s players were forced to leap to the defence of helpless Preston players as they were attacked by sticks and umbrellas as they made their way through the throng to the safety of the pavilion. Ross later ordered a cab to take him away from Hampden but ‘the vehicle was stormed and Ross was severely maltreated.’6

Nevertheless, despite its occasionally disreputable status, there was still a fondness for the old ground at Kinning Park that was exemplified by the turnout of former players to mark the end of its life as a sporting arena on Saturday 26 February 1887, days before the landlord turned the key on the gates for good. Rangers had tried – and failed – to lure Nottingham Forest and Blackburn Rovers north to play an exhibition match to mark the occasion, but it was perhaps more appropriate to field the moderns against the ancients, although the last-minute nature of the arrangements restricted the number of fans in attendance. Old boys such as Tom and Alick Vallance, George Gillespie, Sam Ricketts and William ‘Daddy’ Dunlop all turned out and, although Moses McNeil did not feature on the park, the picture taken before the game shows him sitting proudly with his former colleagues, who were unlucky to lose 3–2 to the younger and fitter Light Blues.