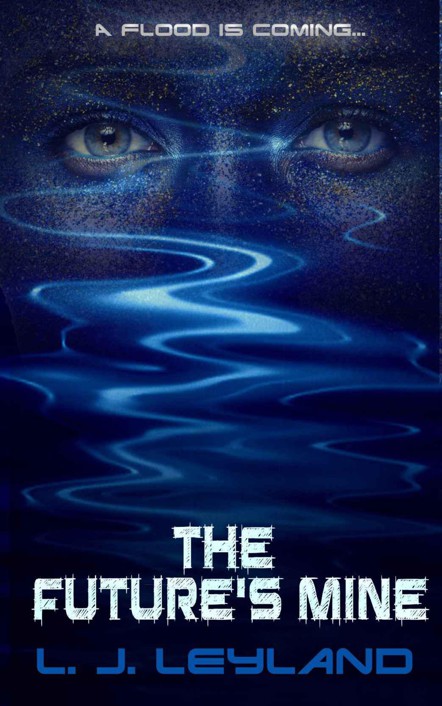

The Future's Mine

Authors: L J Leyland

THE FUTURE’S MINE

L. J. LEYLAND

Maida Winter is seventeen and an orphan. After the Flood drowned the world thirty years ago and the tyrannical Metropole took control of the remaining land, she struggles to survive on the tiny island of Brigadus, with the harsh rulings of the Mayor as final word. After an attempt to raid the Mayor’s home goes horribly wrong, Maida is rescued by Noah - the only person who may hold the secret to overthrowing the Mayor. Determined to expose the Metropole for their involvement in the Flood, Maida becomes a symbol of a new revolution, determined to expose the Metropole for who they really are.

Maida must fight to find out the truth about the Metropole, the Flood, and ultimately, herself.

Let’s get this straight: I am not a thief. I am seventeen years old and I do what I have to do. If sometimes that means bending the laws of the Metropole, I’m OK with that. Like today.

‘Come out, come out, little pig,’ a cold voice hissed.

I shrunk further into my hiding place. My heart began to pound. Could he hear it? Could he hear the fear pulse through my body?

‘I said come out and play. I know you’re in here. I can hear you. I know you’re stealing grain. Naughty, naughty. This grain is for the Mayor, not little tramps like you. And when I catch you, you’ll wish your life was over. At least that way, there’ll be no more pain. When I catch you –

and I will catch you

– I’ll send you to the Mayor. Then we’ll see what fun is to be had.’

My breath came in snatches as though my lungs had forgotten how to function. Paralysis set in. The flesh and bone of my legs were seemingly replaced with granite. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t flee. I was pinned to the spot in fear. I peered from behind the grain barrel to see an Official stalking through the barn. He moved silently, scanning the scene, predator-like. He was looking for a sign of his prey – me. A seventeen-year-old girl who was so hollow through hunger that she would risk her life for the tiny bag of grain clutched in her hands. Hidden behind a grain barrel, and my exit blocked by the Official, the humiliating burn of tears seared my eyes.

Idiot, don’t be so weak, don’t cry.

The dusty air clung in my throat. I closed my eyes and imagined the Mayor’s cold eyes staring back at me. Hatred coursed through me like a poison. I balled my fists, tucked the bag of grain into my pocket and sat up a bit straighter.

‘I’d love to see what the Mayor does to you when he gets hold of you.’ His voice was as smooth as the silk on his uniform. ‘I wonder how long you’ll last. Not long, is my guess. They never last long.’

His barking laugh echoed around the barn and sounded like a pack of hungry wolves.

All this for a bag of grain

. I took a deep breath and tried to focus.

Sunlight filtered down from a hole in the roof where the grain was poured in. There was a rickety ladder that led up to a small platform near the grain hole. The ladder looked ancient; probably no-one had climbed it in years. Huge cobwebs hung between the struts like some sort of grisly party banner. A plan formed in my mind. Admittedly, not a very good plan but it was all I had.

This was my bread and butter, my special talent. Survival and evasion. It had to be, in a place like Brigadus. The Mayor and Officials enforced rules that were impossible to follow unless it was your intention to either die of hunger or get whipped. And I’d rather avoid both, thank you very much.

Strictly speaking, my life was outside the bounds of legality but it was the only way I could survive. It was the only way anyone could survive after we had become colonized by the Metropole in the aftermath of the Flood. Thirty years ago, after the Arctic ice caps melted and most of the world drowned, the Metropole took control of all the peaks of land left. They preferred to use the term ‘Protectorate’ to describe our island, as they thought it sounded more benevolent. They were fooling no-one. We were at the far-flung edge of their Empire, in the North-West cluster of sodden islands that was once the nation of Britannia. The island of Brigadus was all that was left of the Pennine Mountains, which used to stand sentinel over the North. Now, there was nothing but a lonely, muddy spear of land, surrounded by nothing but sea for miles. Home. Or something like it.

After the Flood, the Metropole bribed the Mayor of Brigadus and his Officials. They turned against us, turned against their own people in exchange for food, medicine, and housing. That’s why we called the Officials ‘Parrots’: brainless and squawking, they parroted Metropole Policy and made sure that we were too weak through hunger and fear to stop them. We, the Brigadus people, survived off state rations and whatever scraps we could forage. The Parrots enforced Metropole policy until there was almost no-one left to follow it, having all died of hunger first. It made my teeth grind. So I sought out another way. A less

legal

way of living.

I peered out from behind the grain barrel. The Parrot was at the far end of the barn, lurking by the empty canvas sacks used to dole out the state grain rations. A good twenty metres away. A five-second head start at best. But it was the only choice I had.

Now!

I sprang to my feet and pelted towards the ladder, feeling as though my legs were moving so fast that I had no control of them.

The Parrot took after me like a bullet from a gun. He was quick, quicker than I was. Just as he was about to claw at my heels, a rat shot out from behind the barrel. The Parrot, unable to stop, tripped over his own feet and landed head first in the dusty piles of grain. The rat scrabbled at the Parrot’s face, desperately trying to get away. I clung to my bag of grain and flung myself up the splintered ladder. It creaked but held. The Parrot managed to shake the rat off him. His face was cross-hatched with the bloodied marks of tooth and claw. Blind in his rage, he got up but slipped again and blundered headlong into a stockpile of grain. A few trickles slowly began to shift from the pile. As they fell, they gathered speed and momentum until a grain landslide avalanched down upon the Parrot, trapping him underneath. Fitting really. Buried alive under the might of the Metropole.

As the avalanche settled, dust motes swirled in the air like confetti. ‘Give the Mayor my thanks,’ I called, holding my bag of grain aloft. I could never resist a bit of Parrot-baiting.

I hauled myself through the hole in the roof and sprinted across the wooden roofs of the dockland buildings, jumping from one to another. The watery sunshine warmed my spirits and the fear that had gripped me by the neck disappeared. The sea air was briny and fishy, coloured with the smell of drying kelp and salted mackerels. The breeze made my waist-length blonde hair swirl about me like seaweed in a tide and I laughed as I ran across the roofs, eager to show Edie and Aiden my loot. We’d eat well tonight.

I slid down the drainpipe that crawled up the side of the wooden storage warehouse. I braced my knees as I landed on the roof of a squat, squalid building which was permanently damp and covered in lichen. It was the state fishermen’s log room. Here, under the watchful eyes and eager truncheons of the Parrots, Brigadus fishermen recorded their daily catch. Log books inches thick detailed how much each fisherman caught. Every single measly catch needed to be handed over to the Mayor, or else risk punishment. Every fisherman had a quota and if he did not fulfil it … well, there were

consequences

.

Luckily, we were a naturally cunning race of people on the island. I wouldn’t say

dishonest

exactly but we found ways and means of bending the rules. The fact that the state fishermen’s log room was also the hub of the black market was a piece of delicious irony that was not lost on the crafty folk of Brigadus. I spied in through the skylight and saw that the logger on duty was alone. I pried open the window, dangled my legs through the gap and jumped, landing with a thud on the sea-salted wooden floor.

‘Ah, Miss Maida Winter, nice of you to drop in,’ said Bevan, the oldest and most generous of the black market racketeers. ‘Why is it that I never see you use the door? Always swinging from roof tops or crawling through windows or dangling from trees. Do you have an aversion to walking like normal people or are you part squirrel?’

I laughed and dragged a stool to the counter.

‘I’ve got something for you, Bevan,’ I said. I couldn’t keep the smile from my face.

‘Really? Well, let’s have it. See if it’s worth anything.’ He put down his pen and pushed his glasses up his nose; time to get down to business. I pulled the bag of grain from behind my back with a flourish. I scattered a fistful of grain on the table, waiting for the gasps. They didn’t come.

‘Ta-da!’ I prompted.

Bevan pushed back his stool and hurried to the door. He looked nervously out of the glass and scraped the heavy bolts across, turning the sign to ‘closed’. ‘What on earth do you think you’re playing at, bringing that stuff to me? If I get caught with that you’ll know what they’ll do. They’ll know where it’s come from; no-one else is allowed extra grain apart from Parrots.’

He heaved a weary sigh and buried his head in his gnarled hands. ‘How did you even get this? Do you have no regard for your own life? Even if you don’t care what happens to you, do you care at all about what happens to your brother and sister? You’re all Edie and Aiden have got and if you get yourself arrested –’

‘I won’t get arrested,’ I interrupted.

‘Oh yes, I forgot that you’re invincible.’ His sarcasm stung me.

‘I had to, Bevan. My nets are empty. We’ve not caught any fish for days. The rabbits somehow avoid all my traps and wild mushrooms just aren’t filling us up anymore. You know we don’t get state rations since we ran away. Bevan … we’re

starving.

’

He clucked his tongue and drummed his fingers restlessly on the table. ‘I know, love. But we all are. Especially since the typhoon season came early. You know how bad the rains have been this year. A load of flour went mouldy so they’ve cut back on bread rations for us all. Crops haven’t grown, potatoes got blight. The bloody Parrots have stepped up patrols worse than ever. My men are finding it harder to take their extras from the catch. Look at this log book.’ He thrust the leather bound book at me. ‘Look how empty it is. They’re over-fishing. Hardly anything coming in. And all of it that does come in gets sent to the Metropole. My men can’t take extras because they’re barely meeting quotas as it is. Black market’s just dried up.’

He paused to have a sip of weak homebrewed tea and offered me a mug. I took it and almost scalded my tongue on the steaming hot liquid.

‘Do you know that Jim Franklin nearly had his leg severed off by a man-trap last night? He was on the Mayor’s land, trying to poach deer. The Mayor’s refused him treatment. Said it served him right for stealing.’

‘He can’t do that!’ I cried. ‘He’ll die without proper treatment. You know how bad diseases are this time of year.’

Bevan nodded. ‘Gangrene already. Don’t think he’ll last the day. They’re giving him willow bark to ease the pain. It’s the most they can do. Poor Janette will have four little ’uns to support and no means of doing it. At least you’re young, at least you’re strong. Who’s going to provide for her? Who’ll provide for your little ones if they catch you? You need to think long and hard about what you’re doing, Maida. You need to push that hunger down, every day, push it right down until you feel it no more.’

‘Until I feel nothing at all because I’ll be dead,’ I said quietly.

Bevan shrugged. It was the usual Brigadus response. Death, pain, hunger; all were received with a shrug and a resigned little sigh. ‘I’m sorry, love, but it’s just too dangerous to be trading in grain at this time. Now, if you have herbs or mushrooms from the marshes, I’d be happy to have a look at those.’

‘Forget it,’ I said, standing up and sweeping the grain back into my bag.

‘Take care. Watch yourself and those little ones,’ he called after me. I raised a weary hand in acknowledgement but I was too bitter to say goodbye properly.

I took a right turning as I left the docks and headed for the marshes; the place where I felt most comfortable, hidden amongst the bracken and the sludgy vegetation. Between the Flood and the early rains, the marshes were more water than land and were a breeding ground for diseases, rodents, and insects. A swarm of marsh flies targeted me immediately. They blackened the air as well as my outlook.

‘Bugger off,’ I growled as they searched for a bit of exposed skin to feast upon. Well, at least something was getting a good meal.

I emerged from the trees to find myself facing a cluster of wooden shacks. I walked slowly to one covered in a blanket of lichen and green slime. Jim Franklin’s house. I knocked. Two pairs of inquisitive eyes peeped around the door.

‘Is your mum in?’ I asked.

The children slammed the door in my face. Strangers not welcome. Shifting from foot to foot uneasily, I knocked again and listened for the stomp of Janette Franklin’s feet. Soft, fat drops of rain began to fall and seep into my jacket. Nothing could stay dry for long in Brigadus. Everything was permanently damp through rain, mist or tears.

‘What is it?’ Janette said when she opened the door.

The hot pungency of rotten flesh filled my nose and I staggered back a step. Her eyes were hostile. I held out my grain bag. It was a poor offering in the face of her tragedy. But perhaps the grain could fill the hole in their bellies, although I knew it would not mend the hole in their hearts.

She looked inside the bag and nodded. I turned to walk away.

‘Thank you,’ she croaked as I retreated back into the trees.

What more was there to say? I picked a dandelion leaf from the ground and chewed it numbly. I pushed my hunger deep, deep down, as Bevan told me to.