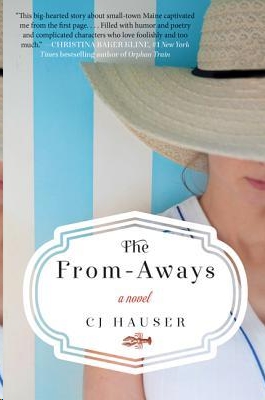

The From-Aways

Authors: C.J. Hauser

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Literary, #Sea Stories

For Boo, Lemo, and Daddio—my family

I will arise and go now, for always night and day

I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore;

While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey,

I hear it in the deep heart’s core.

W

.

B

.

YEATS

Take me down to the paradise city

where the grass is green and the girls are pretty

Oh, won’t you please take me home?

GUNS

N

’

ROSES

Contents

I

have two lobsters in my bathtub and I’m not sure I can kill them.

I’m sitting on the rim of the tub. It has curled brass feet. Everything seems alive and haunted in this house; that’s my first problem.

My second problem is that I pet the lobsters. I roll up a white-buttoned sleeve and run my pinched fingers along the length of Lobster Number One’s antenna. It feels sensitive and unbreakable like coiled wire. Lobster Number One knocks his crusher claw against my hand, but there’s a thick pink rubber band binding it up, so I’m in no real danger. I stroke Lobster Number Two’s antenna as well, so they’re even.

Henry says one lobster boil won’t make Maine my home, but he is wrong.

Both lobsters have dark spotted backs that remind me of Dalmatian puppies. I really should not be thinking of them as puppies.

I get a six-pack from the fridge. This is my plan: I will get blind drunk and then I will kill these lobsters. I tie my hair up in a dark knob. I use the faucet to pry the cap off my bottle. Beer geysers up and fizz plops in the water like sea foam. Henry says his mother, June, gave her lobsters beer before cooking them. She also bathed them in seawater so they’d have one last taste of home. I ask the lobsters, “Do you feel at home?”

Of course not. Some bearded yahoo caught them in a pot. Their home is long gone. As is mine, but no one snatched me up. Instead, I snatched Henry. I married him and begged for us to move to his hometown: Menamon, Maine. I broke the lease on my apartment. Quit my job at the

New York Gazette

. Donated the tangle of wires and smartphones and life-simplifying devices from my purse, because I wouldn’t need them once I left New York.

People use those in Maine, you know,

Henry said.

We’re not going back in time. Just north.

North!

So now I will find a way to do this, because love is boiling the lobsters your freckle-backed husband doesn’t believe will grow you instant roots. My parents raised me an only child in a nineteenth-floor penthouse. No one grows roots nineteen stories deep.

I swing my legs over the side of the tub and stare at my underwater feet. My toes are painted the color the lobsters will be once I boil them. Lobster Number One and Lobster Number Two conference at the other end. I turn over my beer bottle so it glugs empty into the tub. I open another one for me.

We take turns, the lobsters and I, finishing the six-pack. I had imagined tonight so clearly. The boiled red beasts on blue plates. The melted butter in its crock. The wine bottle sweating. The sound of waves through the screen door and of Henry, laughing. A warm breeze wending through the house. I have been imagining this dinner for months. Ever since I started thinking about Maine.

The lobsters jostle around my feet. I look at the empty six-pack and know I won’t be able to kill them.

I splash my feet around in the tub and devise a new plan. I’m going to name them. I get a box of salt from the kitchen and shake it over the water so it will be briny like the sea. I lie on the fuzzy bath mat and wait. It is almost six but the day is still warm. My legs stretch out past the mat and the tiles are cool.

“Leah?” Henry appears in the doorframe, searching for me. “What are you doing down there? The bathroom smells like a bar.”

“Welcome to the Lobstah Bah,” I tell him. Henry’s face is tan and his arms are covered in small scratches. The knees of his jeans are dark-wet and dirty. He has been planting. There have been thorns. He pads over to me in sock feet. He smells sweaty and like mulch.

“Are you okay?” he says. “Why are there lobsters in the tub?”

“Meet Lavender and Leopold. They eat scurf and they have names and so we should not eat them.” Still lying on the floor, I gesture toward the tub. “Don’t they look at home?”

“You stubborn girl,” he says. “I told you we didn’t have to do this.”

I sit up and Henry and I both kneel by the bath. He puts his hand on my back. Lavender and Leopold scuttle to opposite ends of the bathtub. Their carapaces are the color of dried blood and their legs are like machines and I wonder if they are married. But how would I know? I don’t even know their sexes. There is no way to tell which is the boy and which is the girl unless we eat them and see who has eggs inside and who has nothing.

“There wasn’t enough room in the sink,” I tell Henry. “They looked crowded.”

“Naturally,” he says. He leans an arm on the rim of the tub and rests his chin in the crook of his elbow. He looks so much a part of this house, like another piece grown out of it. The lobsters flick their antennae around. “It’s lucky you’re cunning ’cause you’re not much for cooking,” Henry says.

“Do you want to cook them?” I say, and curl into a position like his.

“If you think I’m eating something named Leopold, you’re crazy,” Henry says.

I say, “Let’s return them to the sea.”

We remove the lobsters’ rubber bands and wrap them in a beach towel. At the end of our backyard wooden steps descend to where the grass falls off into rock into sand. To our own tiny boardwalk with a dinghy tied up. To the coast.

The sun is fizzling out and I smell the musk of a small rotting carcass. The ocean stretches wide and green waves tumble in. Gulls are screaming. They have clever faces, spatter-patterned backs, mean spirits. Birds are hollow in their bones. I do not like the way they hang overhead.

I release the lobsters and Henry looks around cagily as they scuttle toward the tide line. If the neighbors see him, he will be laughed out of town. I crack up at the expression on his face.

“Oh sure, laugh,” Henry says. “You’re the one who’s got us on this lobster mission. Guys spend half their lives buggin’ and here we are dropping them back in the sea.”

I count trap buoys bobbing in the deep water, each one marking a pot. It seems like a cruel trick to me. These playful hunks of foam are jail markers, guiding fishermen to the places lobsters have come to practice poor decision making. Traps my lobsters may or may not be smart enough to avoid their second time around. Lavender and Leopold march until a wave crashes and they are gone.

Henry watches the spot where his dinner disappeared. His hair and eyebrows get wild in the sea air. His face tans, so quickly, and already I can see an underglow, a darkening. This is my husband in his natural habitat, in more ways than one. Our house is Henry’s childhood home. His parents passed away five and two years ago. June in an accident. Hank in a boat.

I hug on to him. “I’m sorry,” I say.

“Don’t be sorry,” Henry says. “Jeezum, just don’t buy any more, okay?”

The sun is sunk as we walk back.

T

HAT NIGHT, IN

bed, we are quiet although neither of us is sleeping. I wriggle so Henry can feel my arm against his back, but he doesn’t roll over.

I want to mention that I am good at many things. To start, I am good at writing newspaper articles, which is what I did in New York. I’m also a good cook, a fast runner, and I am excellent at loving Henry. In fact, I did such a stellar job of loving Henry that three months ago he decided to marry me despite the fact that our two ages lumped together didn’t amount to half a century.