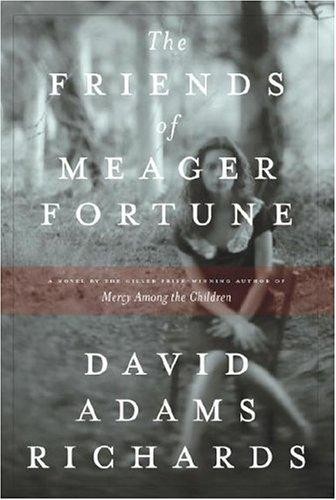

The Friends of Meager Fortune

Read The Friends of Meager Fortune Online

Authors: David Adams Richards

Tags: #Sagas, #General, #Lumber trade, #New Brunswick, #Fiction

ACCLAIM FOR DAVID ADAMS RICHARDS’

THE FRIENDS OF MEAGER FORTUNE

Winner of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize,

Best Book, Canada and Caribbean Region

A

Globe and Mail

Best Book

National Bestseller

“

The Friends of Meager Fortune

is much more than a book noting the intimacies and actualities of the great logging traditions of our shared past … [it is a] book of a town, of a dynasty; a book of epic proportion.… An excellent portrayal of the shallow pettiness of a society on the brink of change.…

The Friends of Meager Fortune

only cements [Richards’s] name as an author unafraid to paint our history and supposed civility in the glaring colours of a raw and often unwieldy humanity.”

—

Edmonton Journal

“The heart of

The Friends of Meager Fortune

is joyful, a celebratory requiem.… The poetry of this magnificently hewn story reveals that pity and woe can be recovered with well-wrought words.”

—

The Globe and Mail

“David Adams Richards is the great tragedian of contemporary Canadian literature.… We are in the hands of a master storyteller.… [The

Friends of Meager Fortune

is] a layered, highly textured novel … a tragic love story of epic proportion.”

—

Guelph Mercury

“A Steinbeck of a book.… One of the most remarkable achievements of this book is the delicate juggling of epic and intimate events.”

—

Calgary Herald

“Given his ear for a catchy phrase, Richards might easily have become a balladeer instead of a novelist.… This sturdily crafted novel … brings an obscure page of Canadian history to breathtaking, vivid life.”

—

The Gazette

(Montreal)

“As in many other Richards novels the lives of everyday people are elevated to a place of meaning, seen from the eye of an educated narrator who artfully creates a story of compelling inevitability.”

—

Toronto Star

“David Adams Richards is one of a handful of Canadian writers whose every book deserves a prize.… [Few] can match [his] simple, powerful language.”

—

The Canadian Press

ALSO BY DAVID ADAMS RICHARDS

Fiction

The Coming of Winter

Blood Ties

Dancers at Night: Stories

Lives of Short Duration

Road to the Stilt House

Nights Below Station Street

Evening Snow Will Bring Such Peace

For Those Who Hunt the Wounded Down

Hope in the Desperate Hour

The Bay of Love and Sorrows

Mercy Among the Children

River of the Brokenhearted

Non-Fiction

Hockey Dreams

Lines on the Water

Copyright © 2006 Newmac Amusement Inc.

Anchor Canada edition 2007

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisher—or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

Anchor Canada and colophon are trademarks.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Richards, David Adams, 1950—

The friends of Meager Fortune / David Adams Richards.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37510-0

I. Title.

PS8585.I17F75 2007 C813′.54 C2007-902577-3

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Published in Canada by

Anchor Canada, a division of

Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limited’s website:

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For my friends

Brian Bartlett, Wayne Curtis, Jack Hodgins, Doug Underhill

And for my sons

John and Anton

With love

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

PART I

ONE

I had to walk up the back way, through a wall of dark winter nettles, to see the ferocious old house from this vantage point. A black night and snow falling, the four turrets rising into the fleeing clouds above me. A house already ninety years old and with more history than most in town.

His name was Will Jameson.

His family was in lumber, or was Lumber, and because of his father’s death he left school when just a boy and took over the reins of the industry when he was not yet sixteen. He would wake at dawn, and deal with men, sitting in offices in his rustic suit or out on a cruise walking twenty miles on snowshoes, be in camp for supper and direct men twice as old as he.

By the time he was seventeen he was known as the great Will Jameson of the great Bartibog—an appendage as whimsical as it was grandiose, and some say self-imposed.

As a child I saw the map of the large region he owned—dots for his camps, and Xs for his saws. I saw his picture at the end of the hallway—under the cold moon that played on the chairs and tables covered in white sheets, the shadow of his young, ever youthful face; an idea that he had not quite escaped the games of childhood before he needed gamesmanship.

If we Canadians are called hewers of wood and drawers of water, and balk, young Will Jameson did not mind this assumption, did not mind the crass biblical analogy, or perhaps did not know or care it was one, and leapt toward it in youthful pride, as through a burning ring. The strength of all moneyed families is their ignorance of or indifference to chaff. And it was this indifference to jealousy and spite that created the destiny Jameson believed in (never minding the Jamesian insult toward it), which made him prosperous, at a place near the end of the world.

When he was about to be born his mother went on the bay and stayed with the Micmac man Paul Francis and his wife. She lived there five months while her husband, Byron Jameson, was working as an ordinary axman in the camps, through a winter and spring.

In local legend the wife of Paul Francis was said to have the gift of prophecy when inspired by drink, and when Mary Jameson insisted her fortune be read with a pack of playing cards, she was told that her first-born would be a powerful man and have much respect—but his brother would be even greater, yet destroy the legacy by rashness, and the Jameson dynasty not go beyond that second boy.

Mrs. Francis warned that the prophecy would not be heeded, and therefore happen. It would happen in a senseless way, but of such a route as to look ordinary. Therefore the reading became instead of fun or games a very solemn reading that dark spring night, long ago, as the Francis woman sat in her chair rocking from one side to the other, and looking at the cards through half-closed eyelids.

“Then there is a choice,” Mary Jameson said, still trying to make light of its weight.

“If wrong action is avoided—but be careful to know what wrong action is.”

“In work?”

“In life,” said Mrs. Francis, picking the cards up and placing them away in a motion that attested to her qualifications.

Mary Jameson had the boy christened Will, and had Paul and Joanna Francis as his godparents. During the baptism, the sun which had not shone all day began to do so, through the stained glass. Mary decided she would keep this prophecy to herself. But she told her husband, who as the youngster grew became more affluent, and spoiled solemnity by speaking of the prophecy as a joke.

Soon the prophecy was known by others, and over time translated in a variety of ways.

It was true Mary forgot about it until the second boy, Owen, was born, so sickly he almost died.

She forgot about it again, until her husband was killed in a simple, almost absurd accident on the Gum Creek Road, coming out to inspect his mill on a rain-soaked day in April.

Mary thinking that it was a strange way for her husband to be taken from her. She almost a grandmother’s age with two small boys. Worse, she had asked her husband to come out on that spring day—frightened that he would take to the drive and be injured, and he was killed by a fall on a road.